D/M-4

Monohull, Irwin 37

37' x 6 Tons, Low Aspect Fin Keel

Jury-Rigged Sail

Force 7-8 Conditions

File D/M-4, obtained from Charles E. Kanter, Key Largo, FL. - Vessel name Lorilynn, hailing port Philadelphia, monohull, center-cockpit sloop designed by Ted Irwin, LOA 37' x LWL 34' x Beam 14' x Draft 4' x 6 Tons - Low aspect fin keel - Drogue: 150% Genoa sail (three corners tied together like a diaper) on 200' x 5/8" nylon three strand rode, with no swivel - Deployed in a low system in deep water midway between Great Anagua and Ackland Islands (Bahamas) with winds of 30-40 knots and seas of 8-12 ft. - Vessel's stern yawed 10° - Drift was said to be very little.

File D/M-4, obtained from Charles E. Kanter, Key Largo, FL. - Vessel name Lorilynn, hailing port Philadelphia, monohull, center-cockpit sloop designed by Ted Irwin, LOA 37' x LWL 34' x Beam 14' x Draft 4' x 6 Tons - Low aspect fin keel - Drogue: 150% Genoa sail (three corners tied together like a diaper) on 200' x 5/8" nylon three strand rode, with no swivel - Deployed in a low system in deep water midway between Great Anagua and Ackland Islands (Bahamas) with winds of 30-40 knots and seas of 8-12 ft. - Vessel's stern yawed 10° - Drift was said to be very little.

A former delivery skipper, Charles E. Kanter has well over 100,000 blue water miles under his belt. He has served as sailing coach to the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, conducted extensive tests on ground anchors, written articles about sea anchors, ground anchors and hurricane mooring systems. On the occasion of this file Kanter and crew were sailing their newly refurbished Irwin 37, Lorilynn, from St. Thomas to the Bahamas when they ran into full gale conditions. To the north lay the treacherous shoals of Acklins Island, and to the west the equally treacherous lee shore of the Great Bahama Bank.

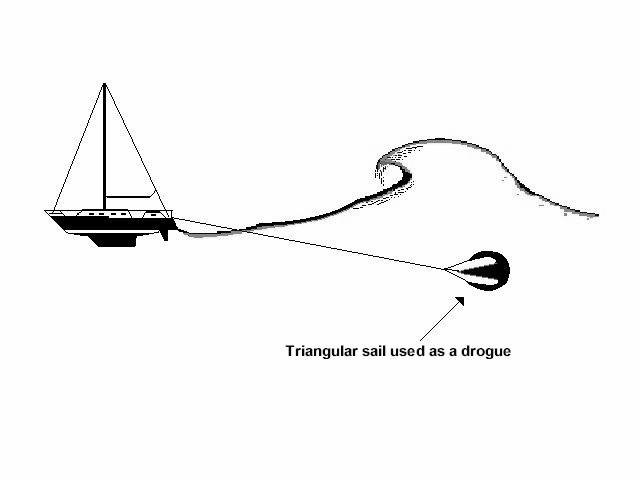

Kanter rigged a "drogue" out of his largest genoa. He tied the three corners of the sail loosely together with dock lines; he then connected it to 200 ft. of anchor rode and carefully deployed the whole thing over the stern. He was able to get the sail to fill and assume a shape similar to a triangular parachute. The boat then lay comfortably stern-to the seas for a period of about 12 hours, more or less anchored to the surface of the ocean. The wind and the rain were so strong that it was impossible to go on deck. The EPIRB, life raft and the calamity pack were made ready just in case. The crew prepared itself for the worst.

Every fifteen minutes one of them would try to poke a head out of the hatch as a lookout, but it was a futile exercise, the air being so thick with spume and spray. In related articles appearing in the February 1985 issue of Cruising World and September/October 1987 issue of Multihulls Magazine, Charles Kanter wrote that he spent the entire night on the cabin sole, agonizing and reflecting on the tactic as it related to the particular boat and situation. As it turned out the center cockpit Irwin rode out the storm quite nicely, without excessive yawing or broaching. Her stern stayed more or less snubbed into the seas, and in twelve hours she had drifted only about three miles westward - the wind being from the east. By dawn the storm had abated and they got under way again, after hauling the "genny anchor" back in. It is interesting to note that Kanter mentions observing large cresting waves breaking over the location of the makeshift drogue:

We found that the sea anchor being close to the surface caused the waves to break before they reached the boat, just like being behind a shoal. It was awe-inspiring. Giant waves would rush up behind us, looking like they were going to overwhelm us and they would, literally, explode when they hit the sea anchor artificial shoal. We never took green water on the deck in the twelve hours we lay there. It looked a little like the famous Hawaii surf, with us standing just far enough up the beach to get a little foam. (Multihulls Magazine, September/October 1987, by permission).

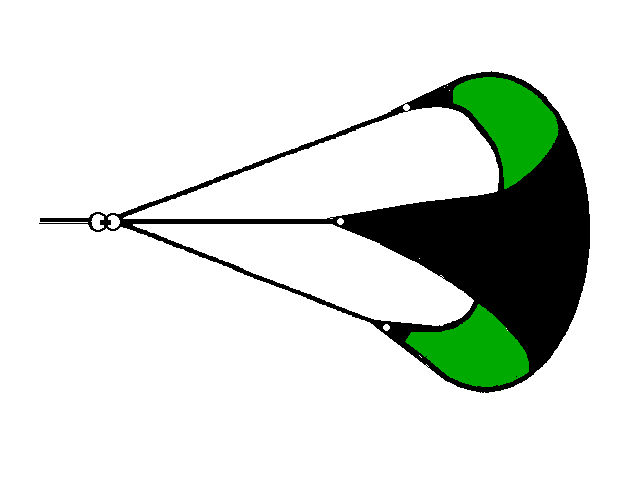

In parts of the Mediterranean where ancient Phoenicians knew of the existence of underwater currents they would lower their sails into the depths and get a tow when becalmed. Sails have great potential for use as makeshift sea anchors and drogues. Think about it. If a sail is strong enough to drive a heavy boat through the sea at several knots, why can't it be used as a sea anchor or drogue to reduce drift? In section 8 of Oceanography And Seamanship, William G. Van Dorn discusses the use of parachutes as sea anchors and adds that a makeshift parachute can be rigged out of any heavy spinnaker, "using three sheets as shroud lines and any spare nylon for a rode." He goes on to say that the forces will be about the same as if it were flying in a strong wind.

Sailors should also read the article Sails As Sea Anchors by Daniel C. Shewmon, appearing in the July/August 1986 issue of Multihulls Magazine (back issues available from Multihulls Magazine, 421 Hancock St., Quincy MA 02171). This article explains and illustrates how to convert sails into emergency sea anchors. Shewmon emphasizes that purpose-made sea anchors should be standard equipment on all offshore boats, but that if the unit is lost or damaged it can temporarily be replaced by a sail. "Mains, genoas, and spinnakers are ideal shapes for conversions to sea anchors.... The key to their success as sea anchors is equal flow of water from all three sides." (July/August issue of Multihulls Magazine, by permission).

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!