Trimaran, Searunner

31'x 18' x 2.2 Tons

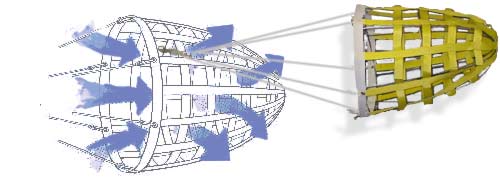

Sea Squid Drogue

Force 7-8 Conditions

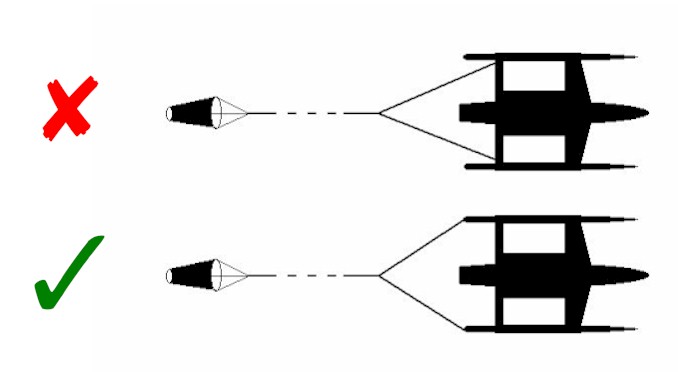

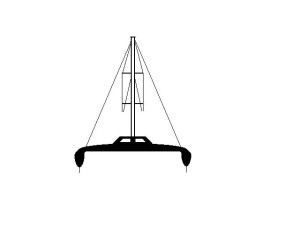

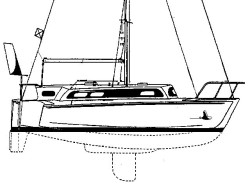

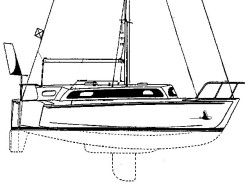

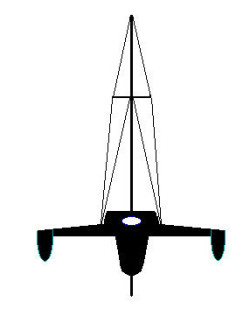

File D/T-6, obtained from Donald Longfellow, Garden Grove, CA. - Vessel name Take Five, hailing port Ventura, CA, Searunner trimaran designed by Jim Brown, LOA 31' x Beam 18' x Draft 6' (3' board up) x 2.2 Tons - Drogue: Australian Sea Squid on 130' x 7/16" nylon braid tether with bridle arms of 30' each - Deployed in Papaguyo winds in 100 fathoms of water about 30 miles off the coast of Nicaragua, with winds of 30-35 knots and seas of 8-10 ft. - Vessel's stern yawed 20° with autopilot steering - Speed was reduced to about 5 knots during 18 hours of deployment.

Another reminder that the Australian Sea Squid is no longer available. Transcript:

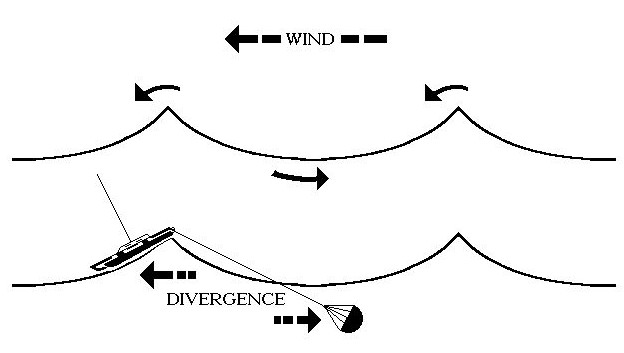

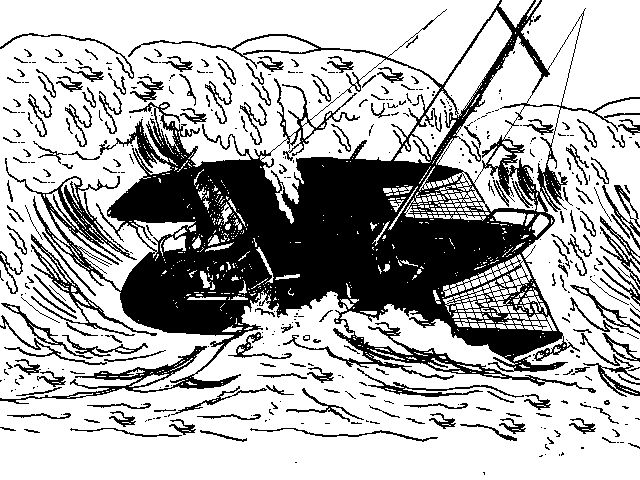

The Sea Squid was deployed 18 hours after leaving Costa Rica and approximately 30 n.m. off the coast of Nicaragua. The seas had grown during the night as my distance offshore grew, and by morning I was becoming concerned about the way the occasional cross waves would knock the stern 40 degrees sideways to the primary wave track as the boat accelerated down wave faces. Neither the electronic nor the mechanical autopilot was quick enough to correct this and I was in no mood to start hand steering. Still, I didn't feel safe risking the boat getting beam-to on the wave faces, especially when it was traveling at over 6 knots. Top speeds down some wave faces were 8-10 kts (double-reefed main up, sailing almost dead downwind.) I didn't want to go bare poles, but I wanted speeds kept under 6 kts. and the yawing reduced. It seemed like an appropriate time to baptize the Sea Squid (it was already hooked up, ready to go).

Over the side it went with no noticeable shock when the line went taut. The effect was immediate and quite apparent, speed down wave faced maxed at 6 kts. (curious though, my ambient speed remained nearly the same as before, 4-5 kts.versus 4-6 kts). Yawing was noticeably reduced. The self steering was now able to handle conditions, allowing me to get much needed rest (singlehanding). Occasionally the Sea Squid would briefly pull free when it was on a wave face. This removed tension on the bridle with unfavorable results. It wasn't a major problem, but I felt it could have been under heavier conditions. Seems to me this could be rectified with the addition of some chain to the drogue's line. There was a Galerider drogue aboard, but I never used it during that trip. It is one size larger than the company recommends for my boat displacement (36" dia. instead of 30"). If I had encountered heavier conditions than the one above, I would have used the Galerider instead of the Sea Squid. There is no doubt in my mind that the sea conditions on that day presented only two reasonable options for my boat: para-anchor, or running down the swells. I would no sooner leave on a cruise without my para-anchor and drogues than I would leave without secondary anchors and heavier headsails.

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!

D/T-5

D/T-5