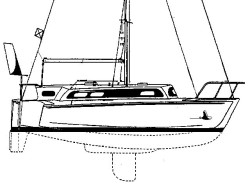

Pocket Cruiser, "Seraffyn"

24' 7" x 5 Tons, Full Keel Cutter

9-Ft. Dia. BUORD Parachute

Force 8-10 Conditions

File S/M-3, derived from writings of Lin & Larry Pardey - See article on "Heaving To" in August '82 issue of Sail Magazine, also pages 268-274 of Seraffyn's Oriental Adventure (W.W. Norton & Co., 1983) and the Pardeys' book entitled Storm Tactics (Pardey Books, 1995) - Vessel name Seraffyn, pocket cruiser, built by Lawrence F. Pardey, LOA 24' 7" x LWL 22' 2" x Beam 8' 11" x Draft 4' 8" x 5 Tons - Full Keel - Sea anchor: 9-ft. diameter Naval Ordnance (BUORD) parachute on 250' x 5/8" nylon three strand rode with Pardeys' own bridle arrangement & 3/8" galvanized swivel - No trip line - Deployed in the Gulf of Papagayo off Mexico and in the North Pacific during storms with winds of 40-70 knots - Bridle arrangement held the bow 50° off the wind - Drift was estimated to be about 5/8 of a knot.

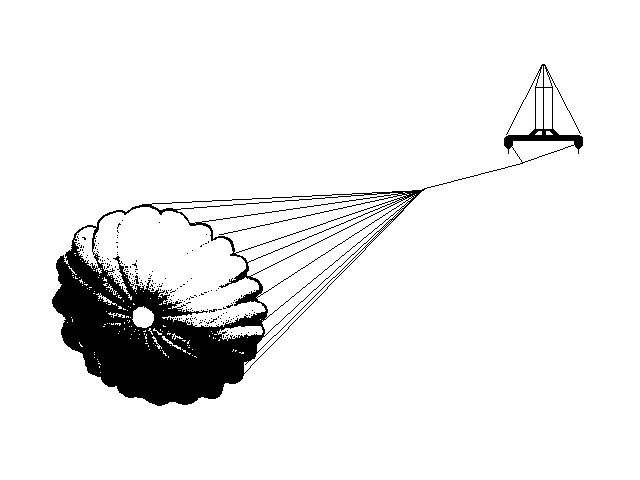

Blue water veterans Lin and Larry Pardey have been using para-anchors since 1970. The one they used on Seraffyn was BUORD MK 2 MODEL 3. This parachute is government surplus and has been in use by fishermen for decades. The canopy is fabricated from heavy, nylon mesh material and it has sixteen shroud lines of 1000 lb. Dupont braid. Patrick M. Royce, author of Sailing Illustrated, did a series of tests on this parachute in 1969 and nicknamed it Two Pennant Storm Anchor (see page 157 of Royce's Sailing Illustrated).

Your author refers to these parachutes as "BUORDS" because they were originally developed for anti-submarine warfare use by the Navy's former BUreau of ORDnances - now Naval Sea Systems Command. Carrier-based S-3 Viking aircraft use such small diameter, heavy gauge parachutes to deliver torpedoes and other ordnances from the air. On page 269 of Seraffyn's Oriental Adventure the Pardeys show two photographs of the BUORD MK 2 MODEL 3. There is also a picture of Larry Pardey holding one up on page 36 of Storm Tactics.

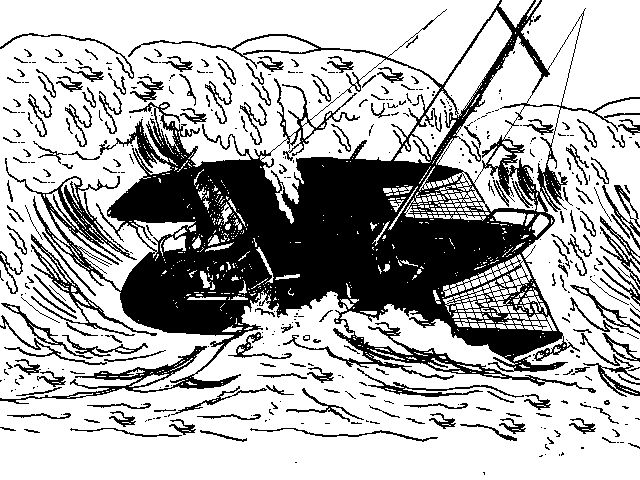

In their original article in SAIL, Lin and Larry reported using this para-anchor in conjunction with a steadying sail in the Gulf of Papagayo (off Mexico) in gale force winds. The steadying sail would luff and flog violently as the boat was frequently pulled head-to-wind. Then it would fill and the head of the boat would fall off. This cycle would repeat itself once every four or five minutes - an uncomfortable and noisy affair. So Larry Pardey later rigged up an adjustable fairlead that kept the bow some 45-50° off the wind, at the same time causing the triple-reefed main to fill quite nicely and dampen the roll. This made the boat heel and lie much more comfortably. As a bonus, Larry found that in this attitude (45-50° off the wind) the boat would "scrape her keel" as she slid slowly downwind, leaving in her turbulent wake a significant "slick" that smoothed the seas, lessening their effect on the boat and gear. "You would be amazed at how this slick breaks down waves and steals their power," wrote the Pardeys to your author. Here is an excerpt from subsequent correspondence (reproduced by permission):

We have a preference for the BUORD surplus chute because 1) it is heavily built, with shrouds on our's almost strong enough to lift Taleisin, 2) it can be purchased quite inexpensively second hand, 3) as it is heavy weight fabric it does not have a tendency to fill with wind when you are deploying it, 4) we have used it since 1970 without problems, and finally, 5) because its fabric stretches when unusual strains come on it, the fabric becomes porous and lets some water sieve through, this absorbs shock loads.

Add this to the stretch of the nylon anchor line and we feel that the catenary curve-effect of chains or weights is redundant. We prefer a dead simple system - no floats, no trip lines, no catenary chains. We are also concerned about the move to bigger and bigger chutes. The bigger they are, the harder they are to store, handle and use. We are not sure they stop drift much better - once a chute is 8 to 15 feet in diameter, the drifts recorded by us on our boats, and during tests with modern sailboats off the Cape of Storms [South Africa], showed that the drift rate with the relatively small BUORD chute was about the same as that listed throughout the Drag Device Data Base for boats using much larger chutes, a drift of between 5/8 and one knot. For monohulls laying at a hove-to position, a smaller chute, combined with the considerable drag of the keel, as shown in the diagram, will produce a wide, effective slick. We can see that multihulls laying head to wind would need the largest chute possible as only the sea anchor is working to create a protective slick.

A further thought on chain. As chafe in the bowroller or fairlead is a major concern with any nylon anchor rode (onshore or offshore), we have considered using a 30 foot length of chain for the inboard end of the rode. But as we have not yet done so, we can make no actual comment on this idea.

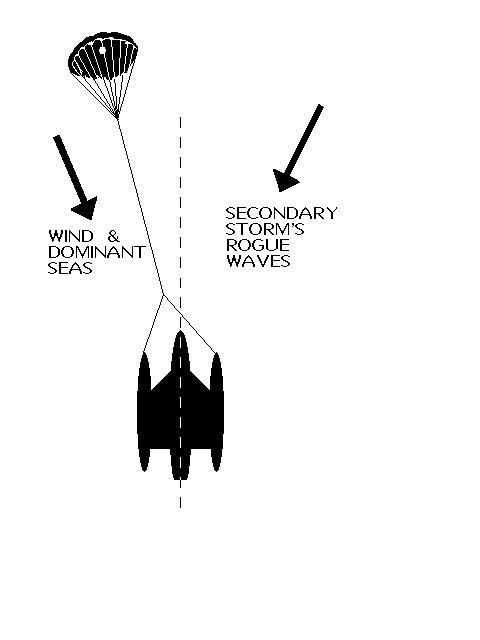

Sea anchor rode is led off the bow. Pennant line from cockpit winch causes the bow to lie 50° of the wind. Storm trysail is set and the tiller lashed to leeward. As the boat is pushed downwind her keel begins to shed vortices, which gradually merge into a turbulent field upstream. The intense mixing effect of this turbulence will tend to cancel molecular rotation - the stuff that waves are made of. Note that this strategy requires square drift. The boat must not forereach - sail out of her protective "slick." The Pardeys have practical suggestions for ensuring that it does not in their book, Storm Tactics - required reading.

To what extent does the turbulence generated by the square drift of the keel affect the shape and ferocity of the waves? The "slick" mentioned by Lin and Larry Pardey is not to be confused with the superficial effects of oil on the surface of the water. It is a more profound phenomenon. It has to do with the turbulent field created by a succession of vortices, technically known as the Von Karman Vortex Street.

Vortices are eddies, created by the motion of irregular shapes in fluids. They flow away from the boundary layer and gradually merge into a homogeneous turbulent field in which the turbulence in one part of the field is the same as that in any other part.

Since non-homogeneous ocean waves are created by the orbital rotation of water particles, anything that interferes with that rotation can have an effect in a seaway. Logically, and if the interference is great enough, the resulting turbulent field can de-stabilize - or at the very least smooth down - the wave formations directly ahead of the boat.