Monohull, Bermuda Ketch

46' x 12 Tons, Full Keel

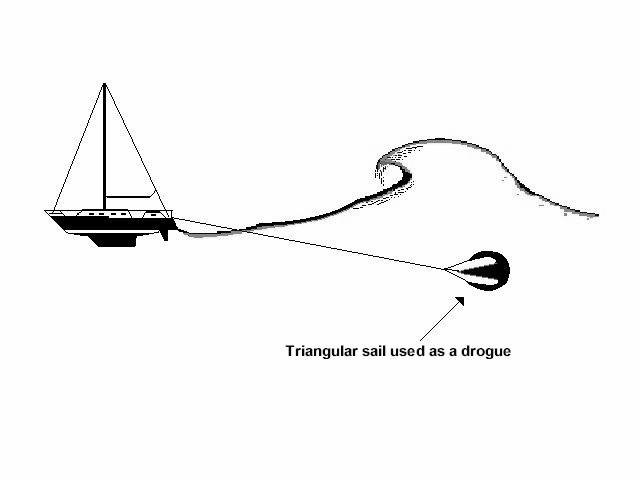

Warp, 60 Fathoms 3" Hawser

Force 10 Conditions

File D/M-1, derived from the writings of Miles Smeeton - Vessel name Tzu Hang, hailing port Victoria, B.C., monohull, Bermuda Ketch, built in Hong Kong in 1938, LOA 46' x LWL 36' x Beam 11' 6" x Draft 7' x 12 Tons - Full keel - Drogue: Warp consisting of 360' x 3-inch manila hawser - Deployed while running before a storm in the high latitudes of the Southern Ocean with winds of 50 knots and seas of 30-40 ft. - The warp had little effect in preventing the pitchpole of Tzu Hang about 1000 miles from Cape Horn on 14 February 1957 - The yacht was sailed under jury rig to Chile, reaching Arauco Bay 36 days later.

This is probably the classic pitchpole in all of yachting history. All the major works on the subject of heavy weather tactics make mention of it. Adlard Coles refers to the 1957 pitchpole of Tzu Hang six times in Heavy Weather Sailing. In her two celebrated attempts to round Cape Horn, Tzu Hang was pitchpoled the first time and rolled the second. On the first attempt she was manned by a crew of three, owner Miles Smeeton, his wife Beryl, and the renowned singlehander John Guzzwell of Trekka fame, (Trekka Around The World, John Guzzwell, 1963).

Tzu Hang had been running before mature seas in the high latitudes (50° South) of the Southern Ocean, trailing 60 fathoms of 3-inch manila hawser. Unlike nylon, manila has the sponge-like quality of soaking up water and was at one time considered to be ideal for use as warps. In this case it was not very effective, for Miles Smeeton writes, "I watched the sixty fathoms of 3-inch hawser streaming behind. It didn't seem to be making a damn of difference, although I suppose that it was helping to keep her stern on to the seas. Sometimes I could see the end being carried forward in a big bight on the top of a wave." (Once Is Enough, Granada Publishing, London, 1984, by permission).

As the boat continued to run before the storm, one breaking wave did come aboard, but Tzu Hang showed little tendency to broach. She seemed to be doing quite well in fact. "It was a dangerous sea I knew, but I had no doubt that she would carry us safely through, and as one great wave after another rushed past us, I grew more and more confident." (Ibid.) At the time of the incident Beryl had just relieved Miles at the helm, and was steering the boat when a great wall of water approached from the stern, so wide that she couldn't see its flanks, so high and so steep that she knew Tzu Hang could not ride over it. Water was cascading down its face, like a waterfall. Miles was down below, reading a book: "As I read, there was a sudden, sickening sense of disaster. I felt a great lurch and heel, and a thunder of sound filled my ears. I was conscious, in a terrified moment, of being driven into the front and side of my bunk with tremendous force. At the same time there was a tearing cracking sound, as if Tzu Hang was being ripped apart, and water burst solidly, raging into the cabin. There was darkness, black darkness, and pressure, and a feeling of being buried in a debris of boards, and I fought wildly to get out, thinking Tzu Hang had already gone down. Then suddenly I was standing again, waist deep in water, and floorboards and cushions, mattresses and books, were sloshing in wild confusion around me." (Ibid.)

Beryl had been catapulted out of the cockpit and into the sea, landing some 30 yards to leeward. Miraculously she was able to swim toward the trailing wreckage of the mizzen mast. Her shoulder was badly injured and it took the combined strength of the two dazed men to pull her back on board. But the situation was now critical. Tzu Hang had received a near death blow. Both masts were gone and there was a gaping - six foot square - hole where the doghouse had been. The weather was not getting any better and she was taking on great amounts of water. She would no doubt have gone down, had it not been for the tenacity and sheer will power of her crew.

From the onset Beryl, although in great pain, did her best to provoke, spur and cheer the two men on into life-saving action. She was the driving force that kept resignation and despair at bay. And John "Hurricane" Guzzwell would soon put his resolve, his backbone and his skills as a carpenter to keep Tzu Hang afloat. He patched the hole in the deck. He sawed and hammered, laminated and improvised, putting back together the pieces that would - thirty six days later - bring Tzu Hang safely into Arauco Bay, Chile. What transpired in those thirty six days on the wastes of the Southern Ocean should serve as an important lesson to all sailors regarding the mindset that is so often crucial to survival itself, the lesson being this: Never give up.

What exactly happened? There is much speculation about the exact movement of the boat during the mishap. Miles Smeeton is certain that it was a somersault: "When she pitchpoled a very high and exceptionally steep wave hit her, considerably higher than she was long. It must have broken as she assumed an almost vertical position on its face. The movement was extremely violent and quick. There was no sensation of being in a dangerous position with disaster threatening. Disaster was suddenly there. Whether she had been 20° to it or her stern directly presented to it, or whether she had been running at 2 or 7 knots could, in this case, have made no difference. Her stern came up and just went on going with no hesitation at all right over the bow." (Because The Horn Is There, Granada Publishing, London 1986, by permission).

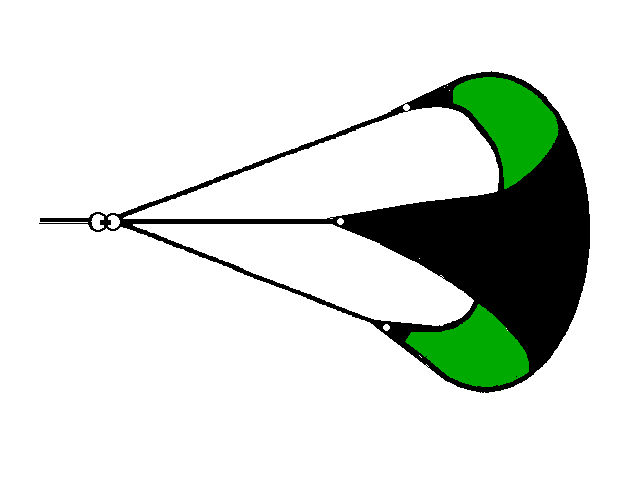

The reader may wish to compare Smeeton's observations with the statement of Joan Casanova (File S/T-1), who survived a similar wave in the Southern Ocean: "It was the type of a wave which pitchpoles yachts in these oceans, the type which every voyager sailing in the high latitudes of the Southern Ocean fears.... We want to stress here that no vessel, multihull, monohull or freighter, could have survived such a sea unless tethered with a long line from a sea anchor...."

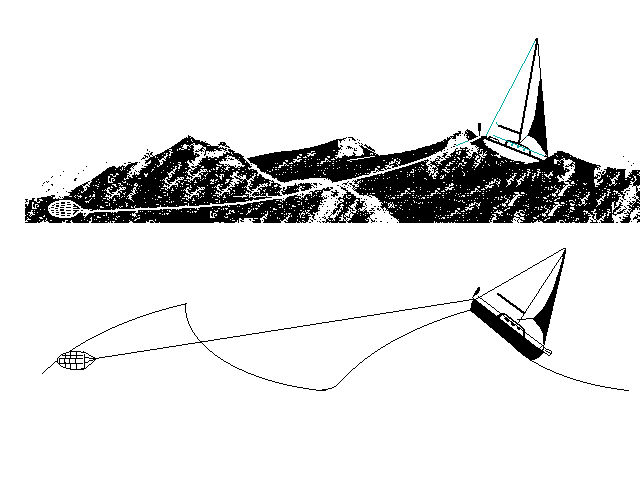

Whereas a rising tide will lift a boat vertically by a force equal to her displacement (usually many tons), a steep wave will "lift" the same boat horizontally with equal displacement force (DF) at wave speed. Speed of molecular rotation is already about 7 knots on the crest of a 40-ft. wave (A). The decaying crest hurls tons of water at a wave speed of 20 knots at her transom (B). Force of gravity (C) drives the bow down into the adjacent trough where it is briefly met with 7 knots of reciprocal rotation coming from the opposite direction (D). Result: The stern goes flying right over the bow without any hesitation at all.

Miles Smeeton later wrote a short Postscript which may be the key to our understanding of the dynamics of pitchpole. This Postscript can be found on the last pages of Once Is Enough and includes the following remarks:

Since I wrote this book I have had a number of letters - mostly from well informed sources - on the reasons for Tzu Hang's two mishaps... the major cause was probably due to the orbital velocity of a big wave. I had never heard of this theory which is that, although the mass of water in a seaway, seen as a whole, is static, each particle of water moves in an orbit around the place which it would occupy at rest. If we were to throw some rubbish overboard so that it represents a particle of water on the surface, we would see it drawn back towards the approaching swell, lifted up, carried forward, and dumped in approximately its original position again; seen from the side it would trace an orbit against the background of sea and sky.

The important thing is the speed at which the water moves in this orbit, and for a forty-foot wave with a ten second period the speed is approximately seven knots. With seven knots on the top of the wave with the wind, and seven knots against the wind at the bottom, a forty-foot ship on the point of a forty-foot wave is subjected roughly to a seven knot push one way at her stern and a seven knot push the other way at her bow, a formidable overturning couple. A longer ship is already overcoming the push at her bow by the time her stern is subjected to the maximum thrust. The answer seems to be to keep forty-foot ships out of forty-foot seas, but if forced to run before them to tow long enough lines so that there is an effective drag in spite of the forward movement of the water on the crest.... (Ibid.)