The behavior of ships on stormy seas is so hard to understand and so important to be predicted, that it is worth any amount of hard thinking, and painstaking observation, and subtle reasoning we can expend on it. J. Scott Russell

We now have 44 drogue files in the DDDB, divided up between a variety of monohulls and multihulls. As of yet the small sample size and the varied data do not allow us to access a specific type of sailboat and render a precise judgment about its behavior and vulnerabilities in storms. On the other hand we are off to a good start when it comes to understanding drogues.

For one thing we now have a clear dichotomy between low-pull drogues like the Galerider and medium-pull drogues like the series drogue; we see the emergence of certain patterns; we can venture educated guesses about the behavior of classes of vessels. We can postulate, for example, that the classes of monohulls that don't tend to behave well with a sea anchor off the bow would tend to behave well with a drogue off the stern because the yaw lever is now reversed.

For the same reason, we can postulate that the classes that tend to behave well with their bows pointed into the seas will tend not to behave as well with their sterns pointed into the seas, everything else being equal. All the more reason for the owner of a yawl, a schooner - or a Prout catamaran with the mast stepped aft - to have a drogue as well as a sea anchor on board.

Speed Limiting (Low-Pull) Drogues

In searching the literature for critical insights about excessive speed we find the following in the writings of John Voss:

To sum up, I have found that breaking wind waves in the open ocean become dangerous only when the vessel is driven through the water, and the faster she is traveling the more damage a sea is likely to inflict. Pooping seas, i.e., seas breaking over the stern when running, are the worst of all. (Venturesome Voyages, Grafton Books, 1989).

One dare not take Voss's words too lightly because the old sea dog was methodical, learning his lessons the hard way plying the seal trade between Vancouver and Yokohama.

Running full bore in storms may be an option for Volvo round-the-world racers. It is not an option for the mom and pop cruiser. Many decades after Voss wrote these words, we find a similar statement in the DDDB, made by John Abernethy, inventor of the Seabrake. Abernethy also learned his lessons the hard way in Australia's Bass Strait.

Heaving-to or using a sea anchor was not the right thing for Abernethy because he was always within a stone's throw of safe harbor. In the middle of the Pacific, Voss was constrained to learn the art of heaving-to. Thirty miles offshore, Abernethy was more concerned about finding ways of ducking back into harbor as quickly and as safely as possible. In making his desperate runs back to harbor the prevailing winds - roaring forties - would have been aft of the port beam. The occasional Southerly Buster would have had him running directly downwind. Running before 50-knot winds and 30-ft. seas in the Bass Strait is no picnic. Likely he would have been towing large game fish behind Papeo as well, perhaps a great white shark - too big to be carried on deck.

Invention arrived on the wings of serendipity. It took two lines to tow big trophy fish, one leading to a hook in the mouth, another tied around the tail. Abernethy learned that he could vary the drag of the fish by adjusting these two lines. Pulling in on the tail line would increase the drag. Slackening off on it would reduce the drag. In a decade or so of doing this he learned the pitfalls of too much and too little speed. Later on in his life he incorporated that wisdom into the drogues he invented. John Abernethy, (File D/M-10):

As a commercial fisherman and charter boat owner based in the most dangerous stretch of Bass Strait, I was routinely operating in heavy seas and often towing large game fish in them. I was frequently involved in Search and Rescue operations as well, towing various types of distressed vessels to safety.

Typically, conditions involved combined seas in excess of 20 feet and sustained winds of 30 knots or more. On many outings I have encountered 50 ft. seas and 50 knot winds.

The incident that occasioned the birth of Seabrake involved 80 ft. combined seas and winds peaking at 100 m.p.h. There were other factors that contributed to the development of Seabrake. Contact with many who have lost vessels in the Bass Strait in the past 40 years, for one thing. My own experience showing that "speed kills," and that conventional cone-shaped drag devices don't assist and in fact can be dangerous, for another. Moreover I have found that towing items such as large game fish, bundles of rope, etc. on a short warp can create too much drag and cause a "stall" at the wrong moment - the bottom of a trough. And towing them on a long warp does not always produce the desired effect either. Drag and restraint can vary from too much to too little, depending on the direction of pull and how much rope remains in the water....

As a final comment I need only repeat my earlier statement, "speed kills." While running before heavy seas it is important to try to keep the speed range below 6-7 knots, but above 3 knots. Slowing down below 3 knots will result in loss of steerage and allow a vessel to wallow, which is equally unsafe....

The ultimate goal is to maintain helm and choice of direction while keeping the ship's speed below 6 knots. In survival conditions the trick is to prevent taking on board any water and keeping the vessel as buoyant as possible, which means avoiding breaking crests or becoming bogged down in troughs. This is only achievable if the vessel has headway and helm.

How much should a speed-limiting drogue slow a boat? We are looking for the speed above and below which something never or always happens - a statistical bounding box. Abernethy's words, "below 6-7 knots, but above 3 knots" may be giving us a glimpse of that box. Average speeds of 3 knots might be found in the lower end of the box. Average speeds of 4-5 knots might be found in the middle of the box. Average speeds of 6-7 knots might be found in upper end of the box.

With this knowledge in hand, a sailor could then try to keep the speed of his yacht within the box by means of the appropriate speed-limiting drogue, or, if necessary, by adding or reducing storm sails, or by making adjustments in rode length, etc. Dr. Gavin Le Sueur, an accomplished sailor and a participant in the rough 1988 Two Handed Around Australia Race, seems to lend credence to the Abernethy bounding box in File D/C-8:

While crossing the Southern Ocean from Perth to Adelaide all competitors went through gale after storm. We could not carry full sail for 3000 miles! We towed drogues and warps for most of the way. The last Sea Squid worked famously.... It was speed limiting to approximately 7 knots. We no longer surfed down waves, and often would add sail before taking in the Squid so that we could maintain a constant 7 knots and not stall in the troughs....

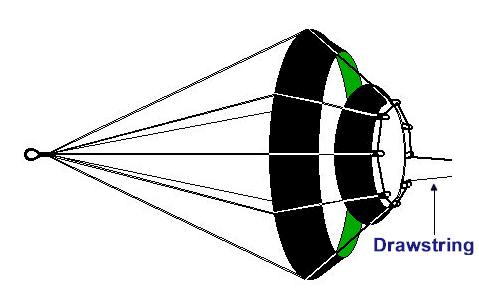

We read about textile drogues and have tried four systems since 1992. The first was a scaled down parachute. It worked out but slowed the cat to less than 3 knots in 35-knot winds. Too slow to avoid getting pooped. We then tried a "series" drogue, provided as a trial. It slowed the boat, but was a stowage mess and very impractical. We then tried a textile drogue that was fluted. It was like a normal parachute (3ft diameter) but with the middle ten inches removed and the continuous shrouds holding the two pieces of material together [see image below]. This fluted drogue worked as well as the parachute - 3 knots and too slow in 35-knot winds and 12ft seas. We had the drogue re-shaped by Para-Anchors Australia, the outlet hole enlarged and a rope tie put into the ends of the shrouds so that we could adjust the outlet [as with a drawstring bag].

In May 1990, the traditionally designed 35-ft. yacht Saecwen deployed an Attenborough drogue (louvered stainless steel design) while running before a storm in the Atlantic. The drogue seems to have slowed the yacht down too much. She began to be overwhelmed by the larger breaking seas. Saecwen was pooped three times in twenty minutes, whereupon her owner Charles Watson retrieved the drogue and ran under bare poles.

Shortly thereafter the yacht was thrown onto her beam ends by a big sea, causing some damage. Watson thinks that a smaller drogue - one with less drag - might have been better, allowing slightly higher speeds. Unfortunately more information was not available. Saecwen's plight is described in the fourth edition of Heavy Weather Sailing and does seem to fall into consistency with the Abernethy bounding box - "below 6-7 knots, but above 3 knots."

The notion that a speed-limiting drogue should not slow a yacht down too much keeps cropping up in both classic and contemporary literature. Predictably, it is a fixture in the school of thought that favors the active approach, at the pinnacle of which one finds the legendary exploits of Dumas and Moitessier.

In File D/M-2 we find Bernard Moitessier towing assorted warps, pigs of iron and a cargo net in the Southern Ocean. As the storm builds he becomes increasingly dissatisfied with the baggage trailing in the water.

At a certain stage he decides to cut away the whole lot and run unimpeded under bare poles, adopting the technique of "putting down the helm" to keep the bow from burying in the next wave. Having done so, he seems much happier, for he writes, "She had no longer anything in common with the wretched boat of the night before which had made me think of the little hunter trying to parry the blows of a gorilla, with his feet caught in the undergrowth."

Perhaps something with less drag would have been more to his liking. Perhaps attaching the warps to a point well forward of the rudder would have allowed more steering and he would not have elected to cut them away. Or, perhaps, with a series drogue deployed he might have been happy to leave the helm altogether and retire to his bunk, instead of fighting it and arguing with the ghost of Dumas. We will never know.

Dana Dinius' use of the Sea Squid in the Queen's Birthday Storm seems to support the speed limits defined by Abernethy's box. Without the drogue Destiny's speed would have shot up to 14 knots. With the drogue in tow, her speed seems to have settled down in the middle-high end of the box. Sailors inclined to the active approach should read and re-read File D/M-12. Destiny's somersault off that rare 80-ft. stacking and cavitating wave notwithstanding, Dinius' account is a defining moment in our understanding of the active drogue approach. Dana Dinius:

We found our drogue set-up to be optimal in conditions that far exceeded what we expected that night. Destiny was held to 3-4 knots in the troughs and 7-8 knots running down the giant wave faces. There seemed to be little or no yawing, and steering control, while being a little sluggish from the trailing drogue, was responsive enough to handle the storm. The ride in general, although very wet, was relatively smooth.

Although the speed was well under control we still felt it necessary to hand steer the boat. The blast of wind hitting the transom as we raised up out of the trough (generally 35 knots in the trough and 80+ on the crest) was strong enough to drive the stern of the boat hard to port or starboard. Reaction had to be quick and complete enough to bring the stern back around before the breaking seas engulfed it. Failure to complete this maneuver left us exposed at an angle to the breaking seas, which would in turn push the boat further around, greatly increasing the danger of a broach/roll. There were times we were hit so hard that Destiny, even with the helm hard over, barely corrected stern to the seas before the next wave crest. It is our feeling that the autopilot (an Auto Helm 6000-Mark II) would not, at the peak of the storm, have been able to correct fast enough to complete the maneuver....

Twice during the night our drogue broke loose and pulled out of the wave behind us. Destiny shot from 7 knots to 14 knots in the bat of an eyelid. Had there been any way to extend the rode at that point we would have, but by then the weather was critical. The cockpit was constantly awash. Hanging on and steering was all we could manage. We learned that, given a shorthanded crew, the rig you go into extreme weather with is most likely what you will be forced to stay with for the duration [emphasis added]. Hindsight tells us that even if we didn't think we would use it, we should have rigged more line. Our suggestion is to have the stern anchor rode rigged so you can attach the drogue at a moment's notice....

We found that directly downwind was the most stable and survivable course. In our case, at 7 knots, burying the bow was not a concern. Our biggest concern was being caught sideways and rolled. We attempted to cheat to the SSW whenever possible to work out of the dangerous SE quadrant of the storm, but found it almost impossible to make much ground without putting the boat at risk of a broach.

Dinius says, "At 7 knots, burying the bow was not a concern." Another important insight. All things are not always equal at sea and relying on speed alone may be misleading. Besides, how can one tell if one is in or out of the bounding box at night, without a large, accurate - brightly lit - speedometer right before one's eyes? Dinius' words give the sailor another indicator. If the bow is burying itself in the base of the next wave, one is probably traveling too fast. If the stern is getting buried by the preceding wave, one is probably traveling too slowly. In File D/M-7 we find the Nor'Sea 27 Synthesis out of the bounding box, burying her nose into the base of the next wave - taking green water over the bow up to the mast now and then. When the 30" Galerider was deployed she seems to have settled down into the low end of the box. George Purifoy:

No longer are we rushing crazily toward a cold swim. The boat has slowed down to about two knots or so, even on the steep downhill faces of the waves. Those monster waves are still rushing at us from astern, but Synthesis just lifts her stern and all the foam and tumbling water just moves by. Beautiful! I still have to steer, but not with the strain and concentration of before. All of a sudden the storm seems manageable.

Note that Purifoy kept the storm jib up for the duration of the time in which the drogue was deployed. Without the storm jib the yacht may have slowed down too much - left the box at the low end - in which case she might have gotten pooped by following waves.

In File D/M-3 we find Southerly becoming unmanageable in the Gulf Stream, her speed racing to 12 knots - well out of the bounding box. The crew deployed the prototype Galerider, whereupon she settled back into the box. Commodore Snyder:

At one moment the boat had been charging like a mad bull, with the helmsman struggling at the wheel; in the next, she was docile and under full control. The helmsman found that Southerly would still answer her helm - though slowly - and that she could steer through about 90°. Everyone relaxed, and the off-watch turned in, even though the motion wasn't all that comfortable, with the cross sea still rolling us 20° either side of vertical. But the boat was safe.

In File D/M-11 we find William A. Forest using a 36" Galerider on his 29-ft. Islander Seraphim in a Pacific gale:

As soon as the Galerider was deployed and the rode adjusted I had instant control. It was amazing.... It should also be noted that I had a 90 sq. ft. storm jib up. In order for the drogue to work properly it is necessary to have forward motion.

In File D/M-17 we find the cutter St. Leger running off in the Queen's Birthday Storm under bare poles, her speed racing to 12 knots - well out of the bounding box. When the 36" Galerider was deployed her speed dropped back into the middle of the box. Michael and Doreen Ferguson:

At about midnight on day 2 of the storm we decided to deploy the Galerider as our boat speed was now 11-12 knots in precipitous seas. We deployed the Galerider using a single line off the starboard quarter, approximately 250 feet of 3/4 inch three strand polypropylene line.... Our plan was to slow St. Leger down, whilst still maintaining steerage using the "Sayes Rig" vane, due to shorthanded crew. Immediately upon deployment our boat speed was reduced to 3.5 to 4 knots and we felt much more comfortable....

We observed the Galerider for hours! A small "half-moon" section of the drogue was visible at times, and we noted the three strand polypropylene tow line did not unwind, nor did the Galerider oscillate or rotate. And best of all, this enabled the wind vane to steer the whole time.

St. Leger towed the Galerider for 60 hours in 60-knot winds, emerging from the Queen's Birthday Storm intact. In all that time the drogue did not tumble, porpoise, squid, kite, zig-zag, oscillate or rotate - a tribute to the inventive genius of Commodore Snyder and the craftsmanship of Hathaway, Reiser and Raymond.

Fine tuning the statistical bounding box is not easy. There are too many variables. For one thing all rudders are not the same - some sailboats are a lot easier to steer than others. For another thing, and depending on hull speed, the entire box may have to be shifted downward or upward. A 70-ft. yacht's bounding box may turn out to be "below 9-10 knots, but above 5 knots," for example. One would need a thousand files - accurate records of exact speed before and after deployment - and computer models to fine tune precisely the box. In the meantime one can take comfort in the knowledge that no computer will ever be able to match the information processing capacity of the human brain itself. Many experienced sailors are already fully aware of the limits of their vessels and know - instinctively - when to subtract/add sails, or deploy a drogue, or lengthen/shorten the rode, for example.

At this stage of the game we can perhaps make educated guesses about the speed ranges that might accommodate self-steering, for example. Destiny's speed range seems to have been at the upper end of the box - "3-4 knots in the troughs and 7-8 knots running down the giant wave faces." She had to be steered manually with Sea Squid in tow. Dinius says, "It is our feeling that the autopilot (an Auto Helm 6000-Mark II) would not, at the peak of the storm, have been able to correct fast enough to complete the maneuver."

Perhaps at the upper end of the bounding box one should plan on remaining in the cockpit and steering the boat manually, everything else being equal. St. Leger's speed range seems to have been in the middle-low end of the box, allowing the wind vane to take over so the shorthanded crew could rest below. Being able to leave the helm and rest below is an important consideration in heavy weather, especially for shorthanded crews.

At what speed range might one be able to hand everything over to an autopilot for a given boat? Well, it looks as though the average speed might have to be brought right down to the floor of the box - say 3 knots for certain rigs or keel types. In File D/M-8 we find the Morgan 382 Windsprint in Force 10 conditions, averaging 7 knots under bare poles without drogue. The owner deployed five 14-inch plastic cones - Davis "flopper stoppers," shaped like Mexican hats. The yacht's speed was reduced to 1.5-2 knots. He lashed the helm and was able to retire below. If the speed had not been lowered sufficiently, he may have had to remain in the cockpit and steer manually.

Remaining at the helm for long periods - days at a time - can be extremely debilitating, even on routine downwind passages. When sailing downwind in strong trades, for example, one had better have a reliable method of self-steering. If not, warps, drags or chain can be used to take the edge off the most extreme turns of speed, making life much more bearable. Slowing the boat will result in an increase in the apparent wind as well, increasing the effectiveness of the windvane. One really needs a good speed-limiting drogue if the wind pipes up to 30 knots and more, however. In File S/M-27 we find singlehander BJ Caldwell deploying one of Para-Tech's 36-inch Delta Drogues in stiff trade winds:

The smaller drogue kept the mast above the water for about 10,000 punishing miles. I trailed it about 100 feet behind the boat whenever there was a risk of broaching. In the Indian Ocean I often had about 15 percent mainsail and 6 percent jib with the drogue out. I ended up using it for about a week during my 21-day passage from Cocos Island to Mauritius....

My average speed with drogue in tow was approximately four knots. Without the drogue I would have been hitting seven, while averaging 5½ knots. I used the device on and off for the whole trip. Instead of yawing and broaching, the drogue would keep the stern aligned with the seas and allow me to still make four knots - and boil water for coffee. I never had to steer manually. The drogue helped the windvane steer in large following seas.

Perhaps the rule of thumb is reversed between sea anchors and speed-limiting drogues. Perhaps in selecting a sea anchor one should err on the large side, but in selecting a speed-limiting drogues one should err on the small side. The consensus seems to be this: one does not want too much drag from a speed-limiting drogue at ordinary speeds. One wants the drag to kick in at higher speeds, when control is becoming difficult.

Anyone who has been foolish enough to lower a bucket into the sea while underway will confirm that the drag of even the smallest drogue can increase precipitously at higher speeds. The relationship between drag and speed is not linear. It increases as a function of the square of the speed: D = f(A, cd, V²), where D is the drag in pounds, A is the area in square feet, cd is the drag coefficient (different shapes have different drag coefficients), and V is the velocity or speed in feet/sec. At 12 knots, even a calf bucket, a crab pot or a plastic milk crate can generate a significant amount of drag - enough to take the edge off the most extreme turns of speed for the average yacht. Purpose-made drogues are much superior to calf buckets, crab pots and milk crates. Well designed drogues - those with high geometric porosity, and those utilizing the guide surface principle - can provide a hundred or so pounds of pull at low speeds, but thousands of pounds of pull at high speeds. And the pull that they provide is smooth and steady throughout the range. The pull provided by the big yellow cone in File D/M-18 was anything but smooth and steady. Wes Thom:

We could look behind and watch the drogue start up a wave as we came over a crest. We could see it tumble on its own crest as we slid down the back side of ours. About the time we were in the trough it would grab again, and up and over the next crest we would go. We could clearly see the yellow cone tumbling repeatedly. It would get rolled, get tossed around, go end over end and everything in between. But it wasn't getting turned inside out, and it seemed to be doing its job when needed.

Unless single element textile cones are carefully fabricated from very porous - mesh-like - fabric, they may behave erratically under tow. Even when they are properly positioned, and even when they do seem to be working, the drag they provide can be a hit or miss, on-again off-again affair, nothing like the steady pull of a Galerider, a Seabrake, or a Delta Drogue.

In File D/T-4 we find BJ Watkins having to abandon the Val 31 trimaran Heart because of the erratic performance of the large, conical drogue - likely the same size and make as the one used by Wes Thom in File D/M-18. The cone was improperly bridled as well, exacerbating BJ's problems It would grab and let go, allowing Heart to surge ahead on wave faces now and then.

In sharp contrast, in File D/C-6 we find Robert Harnwell using a Seabrake GP-24 (guide surface cone) on the Prout catamaran Malaika, with far better results:

Deployed the drogue a number of times across the Atlantic. From England to the Azores the wind was straight behind. In the gale she was surfing 10-12 knots down the big ones, slewing around at the bottom. In a big, heavy boat like ours that's really fast. Deployed the drogue and it slowed the boat down to about 5 knots - like putting on the brakes. At one point had to roll out more jib to keep up speed and control the boat. We had a sail up throughout the 48 hours with the drogue. Most of the time she would track straight, slewing around only at the bottom of the waves.

Owners of Prout catamarans should consider carrying speed-limiting drogues on board, along with the sea anchor. Prouts are among the few sailboats in creation that have their masts stepped aft. With their CEs (centers of effort) farther back, these boats tend to behave well with their bows pointed into the seas, but perhaps not quite as well with their sterns pointed into the seas - everything else being equal.

Owners of Prout catamarans should consider carrying speed-limiting drogues on board, along with the sea anchor. Prouts are among the few sailboats in creation that have their masts stepped aft. With their CEs (centers of effort) farther back, these boats tend to behave well with their bows pointed into the seas, but perhaps not quite as well with their sterns pointed into the seas - everything else being equal.

Unless one moves the CE up by carrying storm sails well forward, boats like these may "slew around" more than others when running downwind. All the more reason to deploy a suitable drogue on downwind legs, or at the very least a warp and chain affair, something that will take the edge off extreme turns of speed, help keep the stern aligned and take the pressure off the helm. With a drogue in tow, the mainsail down and a storm jib well forward, Prouts should be able run downwind - in reinforced trade winds, for example - as well as any other multihull.

In File D/T-8 we find Warren Thomas deploying a 4-ft. diameter conical drogue behind the trimaran Lady Blue Falcon in an unnamed hurricane. The drag exerted by the cone was anything but steady. At times the cone would pull out of the wave faces as well, allowing the boat to lurch ahead at incredible speeds. To compound matters, the bridle being used interfered with Thomas' ability to steer. Warren Thomas:

I used the drogue off the stern of my Piver Lodestar in a mild hurricane 300 miles north of Bermuda, approx. 360 miles east of Cape Cod. Got blown 570 miles in 5 days, running completely out of control. Drogue's bridle would NOT let me steer at high speeds of 22 knots on 2-3 minute continuous runs.

Bridles do not seem to lend themselves to the active approach. John Abernethy does not ordinarily favor their use, preferring to use a single towline so that the boat can be steered with the drogue in tow. Peter Blake did not use one on Steinlager (File D/T-1):

Using the Seabrake without a bridle the trimaran steered very well [without autopilot]. We pulled the centerboard up and the boat basically blew down wind with the Seabrake off the back. It was really great, no keel to trip over, no roll, no yaw, nothing, just straight downwind, fantastic. Multihulls are very good like that, much better than monohulls. No need for bridle, just a single tow line coming to a great big winch.

On one occasion Blake did use a bridle on Enza, however, probably because steering was not an issue. One may have to use a bridle if the helm needs to be left unattended for long periods of time. Otherwise the use of a bridle does not seem to lend itself to the active approach. While bridles do enable the drogue to keep the yacht better aligned when the helm is unattended, they also interfere with steering when it is manned. For maximum steering one should bring a single towline well forward of the rudder.

Positioning a Speed Limiting Drogue

A reminder: low-pull drogues need to be properly positioned. Most of the sailors featured in this publication seem to have done that, positioning it on the back of a wave, with the yacht sliding down the face of one. In this connection Michael and Doreen Ferguson seem to have stumbled onto something important in the Queen's Birthday Storm (File D/M-17):

... as St. Leger slowed down in the troughs of the huge seas the tow line and Galerider tried to catch up to us, leaving a loose coil of 12 to 15 feet of [polypropylene] tow line floating in close proximity to the vane's trim-tab steering paddle.... Mike began bringing in the slack each time we were in a trough, using a primary cockpit winch, until the Galerider was approximately 80-90 feet behind the boat [no resulting slack now]. The drogue was in the same wave as St. Leger, but on the other side of the crest [on the back side]....

We towed the Galerider without incident for 60 hours, with winds at 60+ knots.... At approximately 0800 hrs on day 5 the wind had dropped to 18-20 knots. The low pressure system was east of the Kermadec Islands and moving away from us. The seas were still high, but we readily retrieved the Galerider, which was in almost new condition with no damage or excessive wear after a tough workout!

We should also mention that the New Zealand Air Force Orion aircraft searching the area [for other vessels in distress] made a low pass over us and we advised them by radio that we were OK and not in need of their assistance. Our sails were set and we spent the next week hard on the wind in light northerly winds with very lumpy, confused seas. We arrived safely in Suva, Fiji, where we exchanged tales of the "Queen's Birthday Storm" that claimed three lives and seven cruising yachts. Everyone involved was interested in what "worked" and what didn't.

A strategy that worked in the Queen's Birthday Storm deserves careful attention. Two things stand out in the St. Leger file. The relatively short rode used. The precise adjustment that Michael Ferguson was able to make in its length.

The fact that it was 3/4" polypropylene needs to be considered as well. Polypropylene floats: excessive slack would tend to be quite visible on the surface. St. Leger started out with 250 feet of rode separating her from the Galerider. Slack was being formed in the wave troughs - loose coils could be seen floating next to the transom. Ferguson kept taking in the slack until in the end there was about 80-90 feet of tether separating the yacht from the Galerider, this in 40-ft. seas. This would have placed the yacht and the drogue on different parts of the same large wave (in contrast to the next wave as depicted in the image above).

One advantage of a speed-limiting drogue would seem to have to do with short rode applications such as this. One would never dare use such a short rode for a sea anchor, or even a medium-pull drogue. A low-pull speed-limiting drogue seems to allow it however; something that can be quite useful. For one thing, one can see exactly where the drogue is, and try to position it accordingly, perhaps on the same big wave, as with St. Leger.

This raises another interesting point. Depending on exactly where the yacht and the drogue are in relation to one another, the amount of drag might vary by many hundreds, if not thousands of pounds. In 1994 three drag device manufacturers conducted combined tug tests in Tampa Bay, Florida. Daniel C. Shewmon of Shewmon, Inc., Skip Raymond of Hathaway, Reiser and Raymond, and Don Whilldin of Para-Tech Engineering Company pulled a variety of sea anchors and drogues behind a tug, measuring their pulls on a vacuum gauge. The results were subsequently published in Shewmon's Sea Anchor and Drogue Handbook (Daniel C. Shewmon, 1995). Table 21 on page 153 of this publication shows a 35" experimental Galerider producing the following:

260 Lbs. of drag when pulled at 4 knots

580 Lbs. of drag when pulled at 6 knots

1000 Lbs. of drag when pulled at 8 knots

1600 Lbs. of drag when pulled at 10 knots

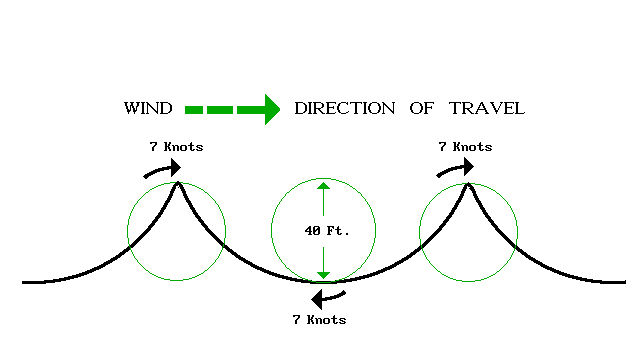

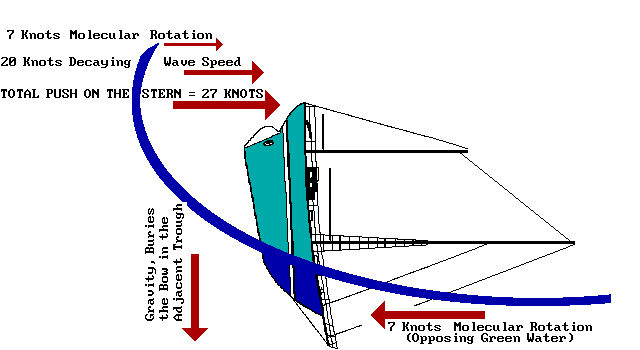

That's a difference of 1340 lbs. between 4 and 10 knots. In theory at least, some of the change that produced the 1340 lbs. could be reproduced by re-positioning the drogue on different parts of a big wave offshore. In 30-ft. seas, for example, the molecular speed of the orbital rotation of such waves may be about 5 knots. With the boat centered on a crest, the drogue centered on a crest and both sailing downwind at 4 knots, the 35" experimental Galerider would provide about 260 lbs. of restraint.

However, with the boat centered on a crest and the Galerider centered in a trough, one might expect a 10-knot divergence , in which case the pull would quickly increase to 1600 lbs. - and much more than 1600 lbs. if the yacht were to be situated in 50-ft. seas.

However, there is a caveat to this: once the wave passes, and the boat is now in the trough, with the drogue now on a crest, instead of divergence we now have convergence. At this point the drogue might well go completely slack!

Most likely this is what Michael and Doreen Ferguson discovered in the Queen's Birthday Storm. The times when the rode went slack were probably the times when the drogue and boat where in convergence on a wave. By progressively shortening the rode they were then able to bring them more and more into synch until they were close enough together on the same part of the wave to avoid the extremes of divergence and convergence.

So where to position the drogue? That would seem to depend on the boat and the conditions on the day. The crucial goal is to avoid having the boat surfing out of control down the face of the wave to then nose plant into the wave in front. By adjusting the length of the rode, as Michael and Doreen did, one can, hopefully, find the optimal position for the day's conditions.

Of course that depends on conditions being safe enough for one to work in the cockpit making adjustments. If that is not possible, then most likely a more passive approach (e.g. longer drogue and/or a medium pull drogue) needs to be taken.

To Quarter or not to Quarter

One of the standard questions your authors ask those who have used drogues in heavy weather is this: "All things considered, would you quarter the seas with a drogue in tow, or would you run directly downwind?"

This is one of the important questions. Should one take the seas squarely on the transom with a drogue in tow, or should one try to quarter them? John Abernethy is of the opinion that, so far as possible, one should try to quarter them. John Abernethy, File D/M-10:

Reading the immediate wave astern and manoeuvring to expose the least amount of stern - quartering the seas rather than taking them on square - is all that needs to be done in order to avoid both the PUSH and the FALL as a dangerous wave passes under the boat.

It should be noted that all of Abernethy's charter boats had wide transoms. The owner of a yacht with a canoe stern might not have to worry about the same "PUSH and FALL." Peter Blake was cautious about answering Victor Shane's question (File D/T-1):

I don't necessarily go along with the idea of quartering the seas [with drogue in tow]. I think that it depends on what you are on, and if you're on a multihull it's definitely much better to be running squarely downwind, because if you're running with the wind on the quarter you're likely to dig a bow [ama] and loose it much more easily. Better to run absolutely downwind [in a multihull]. It's dangerous to take the seas on the quarter, and much, much better to take them square on the transom; that's in a multihull - a trimaran or a catamaran. A monohull, I think, is a different scenario, and I might agree with the quartering idea.

Dana Dinius, after steering Destiny through the worst part of the Queen's Birthday Storm with a Sea Squid in tow (File D/M-12):

We found that directly downwind was the most stable and survivable course. In our case, at 7 knots, burying the bow was not a concern. Our biggest concern was being caught sideways and rolled. We attempted to cheat to the SSW whenever possible to work out of the dangerous SE quadrant of the storm, but found it almost impossible to make much ground without putting the boat at risk of a broach.

St. Leger, on the other hand, seems to have towed the Galerider off the quarter in the same storm, "We deployed the Galerider using a single line off the starboard quarter...." Her owners were on an extended cruise and Shane was not able to confirm this and a number of other points. In File D/M-19 we find Adele towing one of Seabrake's solid MK I drogues off the quarter in Cyclone Bola, around the treacherous North Cape of New Zealand. W.R. Allen:

With the wind generally NW we streamed the Seabrake from the starboard primary winch, which meant the brake was mainly on the quarter, though when the occasion demanded with a particularly big sea we would run straight before. I am not aware of any period when the brake was not on the back of the next wave. On the crest of a wave we would occasionally pull the brake clear [out of a wave face] but it always dug in to hold us for the next one. We made no adjustments to the spring-loaded mechanism which was set to operate [kick in and generate 70% more drag] at 5 knots, and generally we were able to maintain that speed.

(Note that they pulled the drogue out of the face of a wave when their boat was on a crest. It may be that increasing the length of the drogue slightly might have mitigated that problem)

Moitessier took to quartering the seas after he cut away all warps. Probably his predecessor Vito Dumas quartered them as well. One simply cannot believe that Dumas would have chosen to run straight down the wave faces with a full compliment of sails up (he is said to have bragged about never reducing sails in storms). To do so would have buried the bow and produced the cartwheels - "Catherine wheels" - that Moitessier quips about in his imaginary arguments with Dumas' ghost.

"Catch-22"

The criterion that sets a speed-limiting drogue apart from any other drag device is that its low pull allows a significant amount of directional control through the helm. It is an interactive - steering-assist - device, in some sense doing the job of a long steering oar trailing far behind the boat. You can - and may have to - steer the boat while towing the drogue.

All of which brings us back to that "catch-22": The same low drag that allows for steering control may allow the boat to broach, capsize and even pitchpole in a once-in-a-lifetime storm.

The forces that pitchpole yachts are large enough to yank a small, low-pull drogue through the water as they are throwing the yacht end over end. The red-blooded sailors who have made up their minds that the active approach is the only way to go should take note of a number of mishaps associated with this strategy. Out of a total of 38 drogue files, about 20 involve the active approach. We find about 5 mishaps among these, some catastrophic. That's 25%. Food for thought.

Destiny was pitchpoled with a Sea Squid in tow in File D/M-12. Granted, her speed was at the upper end of the bounding box. Granted, the 80-ft. "stacking" wave that she fell off of was a composite - sandwich - of three intersecting waves, the middle layer falling out, or "aerating," as Darryl Wheeler describes it in File D/C-5, allowing the yacht on the top layer to take a death-defying plunge into the green water in the trough. Granted, one may never run into this sort of wave phenomenon in a life-time of cruising. But forewarned is forearmed. Dana Dinius:

Three times during the morning hours, Destiny's keel broke loose [with drogue in tow] and we slid down the wave face like dropping in an elevator. It was at this point we felt control had been lost and we issued our PAN PAN call. As the wind began to clock south and increase again, there developed a secondary wave direction which created a "stacking effect." Ultimately, we feel that's what killed Destiny. Two or three breaking waves stacking on top of one another produced a bottomless situation. Under those conditions we don't think any drogue could have held the boat from that fall. There comes a time in extreme conditions when your survival boils down to the luck of the draw. We feel this was one of those times.

Some might argue that a drogue with more pull might have saved Destiny, but Dinius says, "Under those conditions we don't think any drogue could have held the boat from that fall."

Darryl Wheeler's experience on the catamaran Heart Light would seem to corroborate Dinius' statement. Heart Light was also towing a drogue in the Queen's Birthday Storm, but a medium pull one consisting of a 5-ft. diameter hybrid parachute of some sort. Even with the higher drag, and even though Wheeler was using the two inboard engines (propellers 18 feet apart) to try to keep the yacht aligned, Heart Light's situation was touch and go as well. Darryl Wheeler (File D/C-5):

As the wind built to a steady 77 knots gusting to 90 knots it would drive the 50 foot waves on top of one another. The faces of these monsters were vertical on both sides. In some cases the waves would stack 3 high, with the center wave becoming aerated. When you came off one of these giants the middle wave would drop out and the cat would free fall through the gap until hitting the next wave below.

In File D/M-5 we find the 37-ft. Tayana Hudie running off in a hurricane with warps and various items in tow, including buckets, tarp, sailbags and a submerged 8-ft. fiberglass dinghy. The combined drag was enough to slow Hudie down to an average speed of about 3 knots.

Her owner, Patton S. King, told Victor Shane that from 10 p.m. Saturday until 6 a.m. Sunday morning he could not have been happier with the way things were going. A little after 6 a.m., however, a rogue wave picked up Hudie, carried her sideways, broke and rolled her through 360° in about twelve seconds. Instantly cans, bottles, tables, utensils, floor boards and people were rolling around in total shambles inside - with broken glass everywhere. There was much evidence of roof damage, with extensive damage to the rigging, mast and spreaders. All the crew had sustained injuries, fortunately nothing major. Hudie had to be abandoned.

In File D/T-9 we find the 60-ft. trimaran Great American running off in a storm while lining up her approach to Cape Horn. Rich Wilson and Steve Pettengill kept adding on warps to keep her speed inside the bounding box - likely 8-9 knots on the crests and 4-5 knots in the troughs for this big boat. On Thanksgiving morning 1990, Great American was capsized with twelve warps in tow. The warps were each 300' long, knotted to generate more turbulence.

In File S/M-27 we find Mai Miti Vavau being knocked down while towing one of Para-Tech's 36" Delta Drogues in the Indian Ocean. BJ Caldwell:

It was blowing a sustained 40 knots the night I got rolled 180°. Because the reinforced trades weren't that strong I abstained from switching to sea anchor. With the wind just a few degrees above a dead run with the drogue out, nothing but the staysail up and the boat sealed up, I heard a deafening roar approaching around midnight. Then everything hit the ceiling, including me. When I finally made it back to the cockpit and looked at my mast I couldn't believe it was still standing. I know it hit me broadside, so I think this is what happened: just before the freak wave broke over the boat the windvane lost the apparent wind in the trough and corrected for the loss of wind. As the boat veered upwind the monster erupted across the hull, rolling the boat through 180°. Aside from the torn staysail, bent solar panels and a soaked single-sideband radio, the rollover caused no serious damage to the boat.

The active approach seems to require a man at the helm. At the very least someone on watch. Leaving the helm for prolonged periods may leave the yacht vulnerable. Had Caldwell been in the cockpit he may have been able to round up or steer away from the monster in the nick of time. But singlehanders can't be in two places at the same time. In File D/M-19 we find Adele being knocked down while towing a Seabrake MK I around the North Cape of New Zealand. W.R. Allen:

At 2200 hrs on the 7th March at 33° 36' S, 169° 17' E, we were under bare poles and had set the Seabrake. Shortly thereafter we suffered a 90 degree knockdown, but apart from a few bruises there was no damage. However through this incident we were made very much aware of the confused nature of the seas and that we were catching the odd rogue cross sea.

On the 8th, 9th and 10th March we proceeded in a SE direction following the Three Kings Trough, towing the Seabrake. During this period of heavy breaking seas with winds in excess of 60 knots the Seabrake was in continuous use, doing a marvelous job steadying our progress and giving us a strong feeling of security regardless of the conditions. At no stage did Adele show any tendency to broach and it was always possible to maintain a measure of control, despite the extreme conditions.

Is there a pattern emerging from all this, telling us that vessels using the active approach may be at higher risk than those using passive approaches? We need many more files before we can answer this question. And even then, the answers are not going to be cut and dried. For example, if the helm can be manned around the clock the risk can be reduced significantly. Certainly, the above sailors seem to have derived great benefit from speed-limiting drogues. Each thinks that the active approach was the right one in the given circumstance, in spite of the odd mishap. St. Leger survived the Queen's Birthday Storm intact with a Galerider in tow. And Peter Blake is certain that the Seabrake saved the boat and their lives on a number of occasions (File D/T-1):

The worst case scenarios were on two different occasions. One was on the day we started the race [8 August], and if I hadn't had the Seabrake I wouldn't be talking to you now, probably. And the other occasion was the day and a half before the finish, when I think if we hadn't had the Seabrake there was no way we could have slowed the boat and the lightweight racing trimaran would probably have self-destructed, again because the wind changed and we were being driven headlong into northerly seas by a 50-knot wind from the south. These were very big breaking seas, real breaking waves collapsing down their full fronts....

With a little luck, given enough searoom, and able to work the helm in shifts, expert sailors Peter Blake and his partner Mike Quilter could no doubt survive any situation using the active approach.

But one does not always have searoom. As the Pardeys say in Storm Tactics, "Running onto a storm-swept rocky shore or wave-pounded coral reef is not an option." Moreover one does not always have the skill of a Peter Blake or Mike Quilter to do the steering either. Volvo racers and legendary sailors aside, one gets the feeling that the active approach is not for everyone, even when there is plenty of searoom. Dana Dinius, (File D/M-12):

We feel our chances of surviving the storm were greatly increased by choosing an active role at the helm. This decision took into account exhaustion and exposure. Warm, tropical weather diminishes exposure problems, and as for exhaustion, we've learned in extreme conditions the pure adrenaline pump will keep you going many more hours than you think is humanly possible now. Had we been in a colder climate we may have decided differently. We also realize that an active technique is not for everyone. For those who do not wish an active part, a much larger drogue that would hold the boat at a snail pace, "perhaps" would give the resistance needed to stay stern-to with the aid of an autopilot. We are sure, however, the boat would take a terrible beating given the size and power of the seas we experienced. As it was, we lost most of our cockpit canvas and saw extensive damage to the supporting stainless steel long before the pitch-pole.

Medium Pull and Series Drogue

So far we have only 17 files involving medium pull and series drogues - the passive approach: No steering required or possible. Unfortunately such small numbers do not allow us much in the way of analysis.

All of the vessels using this approach lay essentially dead in the water, their occupants below, their hulls aligned and their sterns snubbed directly into the wind and seas. In file D/M-4 we find Charles Kanter using a genoa sail off the stern, three corners tied together like a diaper. The contraption seems to have worked quite well, playing the part of a medium-pull drogue. No steering was involved or possible. The boat lay essentially dead and buoyant in the water, everything tightly battened down and the occupant resting safely below. The yacht was an Irwin 37 with a well-protected center cockpit.

A reminder that any genoa can play the part of a medium-pull drag device. A number of yachts tried to convert their sails into drag devices in the Queen's Birthday Storm, with varying results. If one looses a drogue due to chafe, for example, sails can be converted into drag devices.

In File D/M-6B we find Gary Danielson using a Galerider and a series drogue on his Ericson 25 in a number of Atlantic gales. In the first mid-Atlantic gale he used the Galerider and found that it greatly enhanced active steering control in 15-ft. seas. However, left to itself (while he was resting down below) it would allow the stern of the boat to yaw too much - 40° off to each side at times. In the second Force 8 gale he used the series drogue. It kept the stern of the boat snubbed into the seas and, in taking total control of the situation, allowed him to remain down below and get much needed rest.

Danielson sailed Moon Boots back across the Atlantic singlehanded in March 1991, using the series drogue in another gale:

At 25-30 knots Moon Boots can't sail upwind effectively any longer. Once the wind got to the low 30's I knew I'd have to put out a drogue. I decided to use the Jordan style series drogue rather than the Galerider because I didn't want to lose any of the ground I'd already gained and the Jordan is a much better "anchor" than the Galerider. In fact, that was pretty much how I decided which one to use on the prior trip also. In any event it did an outstanding job of keeping the stern into the waves and of limiting drift to almost nothing (10 miles in 36 hours, less any westerly drift from possible currents).

Danielson had beefed up Moon Boots' transom area in anticipation of boarding seas. The boarding seas turned out to be a problem for other reasons:

The only problem was that the boat had been broken into in the Canaries and the inside lock for the main hatch had been damaged (the hatch fully closed, just couldn't be secured shut). As you probably know, the Jordan drogue exhibits a tremendous pull at all times. The transom of Moon Boots had been beefed up specially because of this, as had the hatch and the hatch boards. And a good thing too, because every so often a wave would completely go over Moon Boots (I could see solid water as I looked out the side ports).

The problem was that at times these waves would slide the main hatch 2-3' forward. Note that the hatch top itself was custom made of wood, weighed almost 75 lbs., and slid very hard on its track as it did not sit on rollers or cars of any type (just slid on metal tracks). It always took an effort with both hands to slide it open or shut. But these waves would slam it open and at the same time 30-50 gallons of water would pour in, (this happened 9 times in 36 hours). Therefore anyone using this style drogue had better have prepared the stern of his boat properly.

The five 14-inch plastic cones used by Jim Gilster in File D/M-8 almost amounted to a medium-pull drogue, reducing Windsprint's motion through the water down to 1.5-2 knots in 70 knot winds. Jim Gilster:

The five plastic cones were spaced 18" apart; I rigged them up with 5/16" braided nylon, doubled, with a thimble at the bend, and figure eight knots at the holes in the cones. I attached all this to 20' of chain and 300' of 5/8" nylon line, led to the port stern cleat and port sheet winch. I felt confident it would all hold up. It did, in 70 knot winds and 20' seas. We slowed down to 1.5 to 2 knots from 7 knots on bare poles. I adjusted the wheel to allow us to quarter the waves, and we were "comfortable"....

We were occasionally pooped, but with a bridge deck and tight hatch, little water entered the cabin. Although each of the five cones was cracked when we hauled them back in, we did not notice any diminished resistance while "at anchor." I am in the process of affixing two cones together to make five sets of two each, somehow each set of two cones sealed/glued together for strength.

In File D/M-14 we find Professor Noël Dilly using a series drogue on his 28-ft. Twister, Bits. The drogue did exactly what it was designed to do, a testimonial to the ingenuity and hard work of its creator, Donald Jordan. Sailors leaning towards the series drogue should read and re-read D/M-14. Noël Dilly made the drogue himself, out of old spinnaker cloth, using a household sewing machine. Any sailor should be able to do the same, perhaps with a little help from a kind-hearted wife. Note how Noël Dilly prepares Bits in anticipation of boarding seas:

We have massively strong washboards. We seal the cockpit hatch joints with 2" duct tape, also the cockpit locker lids (we have discovered how leaky allegedly waterproof locker lids can be). Finally we move the life raft into its gale storage position, which is on the cockpit sole. It is secured in place by two straps that are jointed by a long pin, such that if you pull the pin the straps are released. This storage has two advantages. First it reduces the weight of water in the cockpit when you get pooped. And second, it is a much more secure place for the life raft than exposed on deck where a breaking storm sea might easily take it, just when it might be needed.

Regarding the motion of the yacht, Noël Dilly says the following:

I think the series drogue ride is a stable affair. Once deployed, description of the new motion of the boat as "bungee jumping" is a good one. Be prepared to hang on, or better still retire to your berth [Jordan recommends that everyone be strapped in by aircraft-types seat belts inside the boat]. In the troughs, she feels loose. As you rise up the wave and the wind hits with full force she hardens up. Surprisingly this is the best time to do things below deck. Usually that's all there is to it, but if you get accelerated by a crest, you can feel it and hang on for the quite dramatic deceleration. Once the crest has passed these things stop, and you are back to the up and down thing. It is all very slow and undramatic, until there is the violent motion associated with the odd crest strike.

In File D/M-15 we are fortunate to find a side by side comparison of a Jordan series drogue and a 2-ft. diameter parachute type drogue. Robert Burns deployed a series drogue of the stern of his 40-ft. center cockpit ketch Peter Sanne in a very nasty gale in the Gulf Stream. He lost it due to chafe. He then deployed a 2-ft. diameter single-element parachute drogue. Robert Burns, after deploying the series drogue:

The slowing effect was phenomenal. Deploying the drogue was like bungee jumping off a 30ft wave with a 40ft. yacht. The feeling of being elastically attached to the sea itself is hard imagine. After a minute or so we had slowed from 8 knots to 1.5 knots. The stern was pointed aggressively into the wind and sea. It was as if we had entered a calm harbor of refuge. The yacht held her position near the top of the waves' crests. When a wave approached and threatened to break on board, the drogue would pull us up and over the top of the breaking waves. There was no possibility of a breaking wave hitting us broadside, as we were always above the majority of the white water.

We furled the remaining portion of the jib, tied off the helm, checked to make sure everything on deck was secured, and then went below. Inside the main cabin the noise of the gale was much less. With the reduction in the yacht's motion, our situation seemed not too bad. We were all exhausted and took the opportunity to try to get some sleep. The time was 2130. I got up several times to check the situation. Despite the roar of breaking seas as we were pulled over the tops of breaking waves, I slept surprisingly well....

The series drogue was lost due to chafe. The motion of the yacht changed:

At about 0230 the sound of waves falling on deck seemed to increase and the motion of the yacht changed. Gone was the elastic "bungee effect." I was about to climb out of my bunk and put on harness to inspect the rig, when the boat heeled sharply to port under the force of a wave striking the starboard quarter. The sound of flowing water was everywhere. In the next instant the companionway doors shattered, and an angry stream of water rushed into the saloon.... I reached for the nearest overhead light... it came on to reveal the main saloon with 2-3ft of seawater sloshing above the cabin sole. Debris of the splintered hatch floated with charts, books, wet blankets and sleeping bags. The cockpit was full to the top of the coamings with frothing sea water. The night was dark, but I could still make out the towering peaks of white water around and above us. I glanced at the wind instruments; we were lying with the wind just aft of the beam, we had no headway. "So," I thought, "this is what it is like to lie a-hull." The priorities were to clear the boat of water, and try to repair the shattered companionway in case we were boarded by another sea. And to check what had happened to the drogue....

I found the bridle dangling over the transom, severed on both sides. The 3/4" nylon bridle had been abraded by the self-steering mounting brackets. There was damage to the stern pulpit and deck fittings, evidence of the forces and motion exerted on the hull by the drogue before it parted the bridle.

Burns deployed his backup drogue - a 2-ft. diameter conical parachute. Note the difference in the behavior of the yacht:

When all 300 ft of line was out and the chute was subject to some forward motion the line came taut. There was no bridle now, so the tow line was only attached to the starboard stern cleat. The yacht yawed to port, aligning the stern almost into the wind and sea. Our forward velocity was about 2 knots. Big waves would cause us to surge forward and down the waves faces, as the chute didn't have sufficient surface area to slow us down against the push of big seas....

Gone was the feeling of "bungee jumping" [associated with the series drogue]. The forces exerted by the chute were sharper [jerkier] and nowhere near as powerful. However, the strategy of lying stern-to was still the most comfortable and safe. The little chute did well. We had no serious broadside wave strikes, even though there were still a lot of breaking seas around us. The chute was not able to pull us up and over the breaking waves, so the occasional wave dumped on the stern. As the yacht had a center cockpit, there was less danger of it being filled....

There are a number of things to be said about this file, not the least of which is that we have more to learn. One can reasonably assume, for example, that if all this had happened in more severe conditions - such as those typified by the Queen's Birthday Storm - the difference between the performance of the series drogue and the little parachute would have been far more pronounced, even critical.

Also, in reading this file one can't help worrying about the integrity of the hatches and washboards on production boats - Victor Shane's persistent worry about the passive drogue approach. Granted, Peter Sanne's companionway was shattered after the series drogue was lost. But note what Robert Burns says:

... the boat heeled sharply to port under the force of a wave striking the starboard quarter. The sound of flowing water was everywhere. In the next instant the companionway doors shattered, and an angry stream of water rushed into the saloon....

If a wave striking from the starboard quarter can shatter the companionway doors of a center cockpit boat like Peter Sanne, what might it do to a production yacht with a stern cockpit? The implication is quite clear: one should never take anything for granted about the integrity of the companionway on any yacht. If one is going to opt for the passive approach, the hatch and washboards had better be massive, otherwise the sea will find a way of breaking through. The series drogue is a marvelous contraption.

Judging by Burns's description of the behavior of Peter Sanne, Donald Jordan's brainchild provides an ingenious method of keeping yachts aligned in storms, providing one can keep the sea out.

Your authors worry about the "people risk" as well. There is little to worry about as long as people stay out of the cockpit. But what if something needs to be tended to - a problem with chafe, for example? Since the yacht is more or less stationary in the water, any breaking wave striking the cockpit directly may severely injure someone in it. Being slammed into a steering pedestal or fiberglass bulkhead by tons of fast moving water isn't all that different from being slammed into a windshield during an automobile accident. Roger Olson, File S/M-22:

As the weather deteriorated I ran off with storm jib and storm trysail. I considered dropping the trysail but wanted it up in just case I decided to heave-to. Deployed two "MINI" tires [makeshift drogue] off the stern for better control. Wind and seas not too bad (40 to 50 knots) and it was going in my direction. A huge wave broke next to us, depositing ample amounts of water on me and filling the cockpit. It doesn't take a genius to realize that if the wave had been over the stern I would have been rammed against the flat aft side of the cabin. Also, I could easily imagine this wave carrying me to the end of my harness tether. If the tether didn't break it would surely break my ribs. So I decided to come about and heave-to.

Xiphias was "going with it" - running and being steered. Even so, Roger Olson could see how that he might be seriously injured by a breaking wave. With a series drogue deployed a yacht is more or less dead in the water, hence the threat of bodily injury has to be taken very seriously. When working on a slippery bow, deploying a sea anchor, for example, one is usually in a crouched position, on one's knees, or even lying flat, hanging on for dear life, facing forward, reading the approaching waves and always anticipating trouble.

Standing in the cockpit one tends to be more at ease, likely to let one's guard down. In the cockpit one is usually standing up, with one's back to the boarding seas as well. Here also, one should be in a crouched position, facing astern, reading the approaching waves and always anticipating trouble.

In the Coast Guard report that he co-authored, Donald Jordan - the inventor of the series drogue - writes the following:

The cockpit may not be habitable and the crew should remain in the cabin with the companionway closed. In a severe wave strike the linear and angular acceleration of the boat may be high. Safety straps designed for a load of at least 4g should be provided for crew restraint.

One should not venture out into the cockpit area with any sort of a medium-pull drogue deployed. If it is absolutely necessary to do so, one must wear a padded PFD (personal flotation device) with some sort of head gear, and one must have one's safety harness snapped on at all times.

Moreover one needs the assistance of someone standing in the companionway to warn of approaching danger as well. When Dana Dinius was grappling with Destiny's helm in the Queen's Birthday Storm, Paula Dinius was braced in the companionway with her head out of the hatch, helping him read the waves that he could not see behind him. When a great wave would approach she would give a shout and Dana would correct the helm ahead of time, without looking back.

This sort of teamwork may be called for if one ends up using the active approach in a life-threatening storm. It is absolutely called for when one is using the passive approach and someone has to go out into the cockpit area. Any crew member venturing out into the cockpit must do so under the close supervision of a "Paula-watch" - a new nautical term!

This Paula-watch must brace himself or herself in the companionway - washboards in place, head poking out of the hatch - wearing foul weather gear, a PFD, a safety harness.

Stout hand rails must be installed on both sides of the companionway in the interior of the yacht so that the Paula-watch can hold on with both hands while standing on the companionway steps and looking astern. The steps themselves must be surfaced with anti-skid compound - or tape.

He or she must wear safety goggles, ski goggles, or Uvex goggles so as to be able to look directly into the maelstrom. The watch must not look at the individual in the cockpit, but rather keep his or her gaze fixed astern, so as to be able to read the approaching waves and serve as eyes and ears for the person working in the exposed cockpit. The watch must give a loud shout - or blow a whistle - if he or she sees a dangerous sea coming, so that the individual in the cockpit can "hit the deck" and hang on for dear life. Methods of communication must be established among crew members to this end - voice signals or whistle blows that can be heard above the screech of the wind. Whistles must be the sort that will continue to sound when drenched with water.

Having said all that, maybe the risk of boarding seas, when static in the water using a Jordan Series Drogue, is not as high as one might expect. Typically the water cascading forward from a breaking wave falls onto something that is positioned on the face of the wave and is sliding (surfing) down that wave. As the wave breaks, the boat is carried with it, and thus stays positioned right under the crashing water. With the Jordan drogue in tow, the boat is static and, as Robert Burns said:

The yacht held her position near the top of the waves' crests. When a wave approached and threatened to break on board, the drogue would pull us up and over the top of the breaking waves. There was no possibility of a breaking wave hitting us broadside, as we were always above the majority of the white water.

Instead of sliding down the wave under the force of tons of falling water, the boat stays static, and the wave, with its breaking crest, passes below.

Do we know for sure that this is what happens? Unfortunately not - we need many more reports of boats using Jordan drogues in serious weather before we can draw any firm conclusions. Comparative reports, such as Robert Burns' with and without the series drogue are particularly useful.

The series drogue was specifically designed for the passive approach. The "bungee jumping" alluded to by Noël Dilly and Robert Burns is a saving grace, not a danger. Bungee jumping to a series drogue is not to be confused with bungee jumping to a large sea anchor off the stern. The former would be analogous to jumping off a bridge with bungee cords attached. The latter would analogous to jumping off a bridge with ordinary rope attached.

Unlike a large sea anchor, the series drogue allows a great deal of precisely tailored yield in the event of a wave strike. With anything bigger off the stern the yacht will surge ahead, only to come up short against the pull of a large, unyielding device. Even if the device is a relatively small parachute, the yield signature is not the same as that of the series drogue.

In file D/T-2 we find delivery skipper Thomas Follett using a 5-ft. diameter Shewmon sea anchor off the stern of a 60-ft. trimaran in Force 9-10 conditions. No steering involved. The boat was brought to a grinding halt and stayed glued where it was for 36 hours. With only 100-150' of rode payed out Follett reported that there was unbearable strain on the everything, "too great to risk paying out any more line after we got the thing made fast."

Days later he used a 3-ft. diameter Shewmon low-pull drogue off the stern of the same boat. "Worked much better," he reported, "lots of shipping about and we could maneuver with the engine (drogue still out) whenever necessary. Didn't stop us but slowed us down a lot and was very comfortable."

In file D/C-1 we find Walter Greene deploying a 4-ft. diameter Shewmon sea anchor off the stern of the 50-ft. catamaran Sebago. No steering involved or possible, and great strains again. He said, "The sea anchor really beat the hell out of the boat - deck gear and waves crashing on the boat."

Victor Shane is of the opinion that medium-pull drogues require much longer rode lengths. This is in marked contrast to the use of low-pull devices where one can tailor the length to the conditions, and very short lengths can sometimes be optimal.

Had Walter Greene used 600' of rode instead of 250-300 feet he would no doubt have found the seas much more comfortable. Had the crew of Rogue Wave (File D/T-3) been able to let out 500' of rode instead of only 150', no doubt they too would have found the seas much more forgiving.

In File D/C-2 we find John Kettlewell deploying a BUORD para-anchor off the stern of his 31-ft. catamaran Echo. This ordnance parachute has a porous canopy with an inflated diameter of about 6 feet, making it a medium pull-drogue for some vessels. Kettlewell was wise enough to pay out 400' of tether and the crew was able to go down below and get some rest on the floor of the saloon area. John Kettlewell:

In general we were very pleased with the performance of the drogue. As I stated previously we could not lie bow into the wind with this size chute. I wonder if we had removed our roller furling jib we could have laid bow to.... In any case I'm sure I would now prefer to run before the seas on this boat. Our cockpit is well protected with a strong door and great drainage due to the motorwell for the outboard. I think it is useful to give with the punches of the waves. We even raised our rudders to take the strain off them from wave hits.... With a bridle to each stern the drogue held us straight on to the sea and we did not have to steer....

Our rode consisted of 2 x 200' lengths of 1/2" nylon connected by a large shackle in the middle. I feel your length recommendations (i.e., LOA x 10) may be a bit short. I was certainly happy I had 400' of rode!

Perhaps the rule should be changed to LOA x 15 in association with medium-pull drogues. Had Kettlewell deployed only 200' of rode Echo would no doubt have taken a terrible beating. But such beatings can be expected when using any sort of medium-pull drogue in storms. Dana Dinius, File D/M-12:

For those who do not wish an active part, a much larger drogue that would hold the boat at a snail pace, "perhaps" would give the resistance needed to stay stern-to with the aid of an autopilot. We are sure, however, the boat would take a terrible beating given the size and power of the seas we experienced. As it was, we lost most of our cockpit canvas and saw extensive damage to the supporting stainless steel long before the pitch-pole.

In File D/C-9 we find the 44-ft. catamaran Anna Kay taking a terrible beating in the Gulf of Tehuantepec. She was using a 9-ft. diameter Shewmon sea anchor off the stern with only 250' of 3/4" tether. Given the diameter of the drogue, and given that wind was blowing 120 knots, Anna Kay might have fared a lot better with 600', 800' or even 1000' of line out. One can't help thinking, though, that a series drogue might have been the salvation of this boat.

The sailor who leans towards the active approach will argue that he would prefer something that didn't stop the boat entirely. The sailor who leans towards the passive approach might argue that he would prefer a drogue that could take total control of the situation, allowing him and his crew to rest down below - out of harm's way. The former may have a yacht with a wide, vulnerable transom. The latter may have a double-ender with a well protected center cockpit. Or perhaps a multihull with lots of stern bouyancy. The former may be trying to inch his way out of the dangerous quadrant of tropical storm. The latter may be wanting to anchor his ship and allow a fast moving front to pass overhead.

Any number of other variables might come into play in the making of such decisions. Every situation is different, every crew is different, every boat is different, every gale is different. The decision as to which approach to use must take into consideration many factors.

Looking to the Future

One would hate to think that a method of investigation, hopefully well worked out in the pages of this book, might end up as a consumer device to push sea anchors or drogues as "magic bullets."

There are no magic bullets at sea.

Only human ingenuity, coupled with the obstinate tradition of seamanship will answer. Sea anchors and drogues are products of human ingenuity. Both belong in the inventory of a cruising yacht. Both have already saved life and property at sea. With their vices and virtues clearly understood, they stand to save much more in the future. Victor Shane himself would not think of putting out to sea without several drogues and several parachute-type sea anchors. We find many of the sailors featured in this publication expressing a similar sentiment. Jeremiah Nixon, File S/M-5:

These are some of the reasons why I consider this equipment the most important safety item on my boat.... I will never make an ocean passage without one on board. People must realize that ocean cruising can be safe if you go with the idea that you will go into a defensive position before the seas build too high. The flat-out philosophy of professional racers must be disregarded by the small crew cruising yachts.

Captain Jerry Sidock (File S/M-9):

I would like to say that I don't think that common sense would permit me to leave shore without my sea anchor. It is just too difficult at times to continue on when short-handed, or rather single-handed, as I am most of the time. It is at that time that I look for assistance from other sources, such as a sea anchor.

Solo circumnavigator Brian "BJ" Caldwell, File S/M-27:

I don't know how our family cruised for six years without this. There's no excuse for leaving on a long cruise without a sea anchor and a drogue....

Delivery skipper Phil Herting, File S/T-9:

I hate to think of the situation if we had not had the para-anchor with us. It should be considered a vital piece of gear when making any substantial offshore passage.

Delivery skipper Warren Hawkins, File D/M-9:

The very instant that the Galerider took hold it was as if you had pushed a button and calmed the gale. We made a quick jury-rig repair on the tiller (which lasted all the way to Honolulu) and the motion of the vessel was such that we could take normal steering watches on the tiller and the off watch could get some sleep.

Sir Peter Blake, File D/T-1:

We just about lost the boat on two occasions at that point going down the mine, until we got the drogue out the back and then suddenly we could relax. That really was a matter of survival. It was an "if we don't get the drogue out we're not going to be alive" scenario. There was no maybe to it that time.

Are we arguing towards an implicit hypothesis? Are we subjectively handling the data in such a way that our optimism undermines our objectivity? To date we have not compiled nearly enough files to do the subject the justice it deserves. And yet there is great promise in these initial studies. The subject, although complex, would seem to be tractable.

A foundation has been laid upon which one can make claims, not that certain things will always happen, but rather that certain things will probably happen. We hope thus to adhere to the spirit of the scientific method as we understand it and thereby to leave open the way to more learning. Certainly we have a lot more to learn on this vast subject. As more and more files are added to the DDDB, we will learn more about various classes of vessels, keel types, rigs, hull shapes, tethers and the many modes of deployment.

For this reason we implore you, if you have been through a survival storm, whether or not you used a drag device: please submit a report to us. The more reports we have, the better we can all learn. Likewise, if you know someone else who has been through such an experience, please encourage them to contact us.

There are at the same time limits to everything on this earth and we will never achieve the level of certainty that some seem to demand of life. By now, all the same, we can feel secure in a substantial practical knowledge of the ways in which drag devices can play an important part in safety - and even survival at sea.

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!

just bought an Attenborough drogue but it has the 4 stainless steel arms missing any one got any.

Lots of gales, including in the Celtic Sea/Fastnet area but survival storm was in the Med heading from Ibiza to Majorca in June 2014 on a Lagoon 50′ charter yacht. Had steady winds over 50 knots and gusts over 60. I was terrified as had my three kids and my sister aboard but remained on flybridge with both engines on doing 5-6 knots and bare poles. Passed right through the eye of the storm and boat stayed on rhumb line as if it didn’t really notice the weather. My ignorance was terrified me the most though so many thanks for this help !

Glad that you came through that without problems. ‘What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger’ 🙂

I am guessing that you did not use any drag devices at that time. Were you to find yourself in the same situation, do you think you would deploy one or other type of drag device next time?