S/C-1

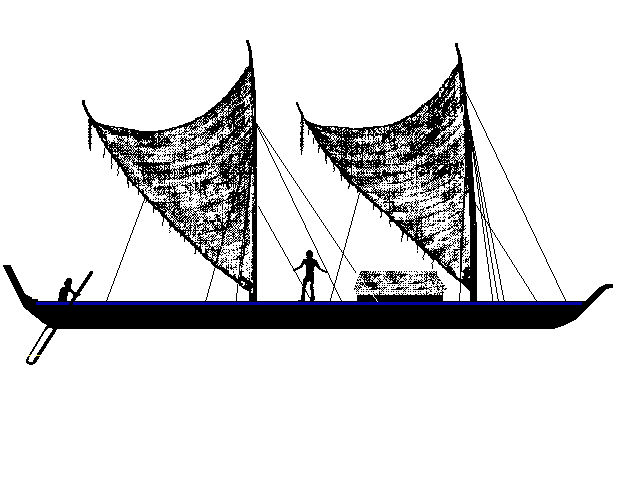

Catamaran, CSK

65' x 30' x 22 Tons

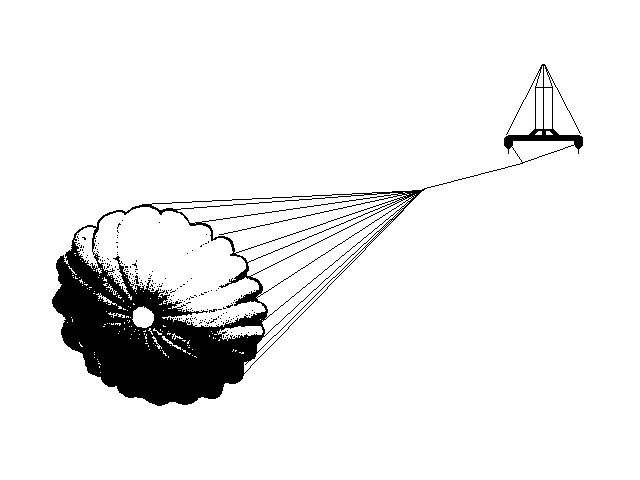

28-Ft. Dia. Parachute Sea Anchor

Force 8 Conditions

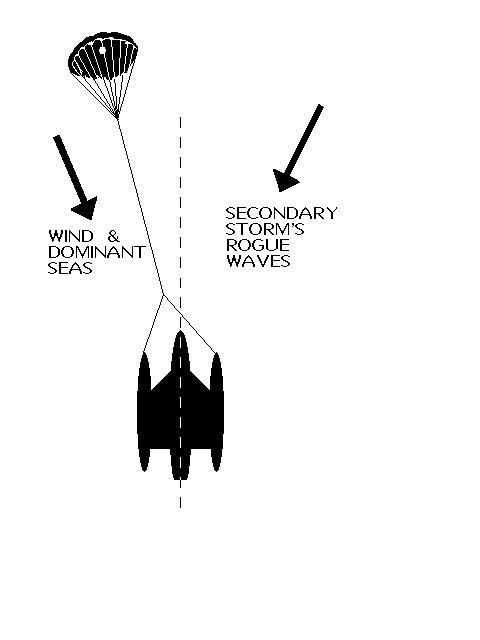

File S/C-1, obtained from Bruce Reid, Costa Mesa, CA. - Vessel name Rose Marie, hailing port Vancouver, BC, catamaran, designed by Vince Bartalone, LOA 65' x Beam 30' x Draft 3' 3" x 22 Tons - Sea anchor: 28-ft. Diameter C-9 military class parachute on 500' x 1" nylon three strand tether and bridle arms of 60' each, with 5/8" galvanized swivel - No trip line - Deployed in gale force winds in shallow water (40 fathoms) off Point Conception, California, with winds of 40 knots and seas of 15-20 ft. - Vessel's bow yawed 5° - Drift was upwind at 2 knots, induced by current.

Rose Marie was on her way to Vancouver from Newport when she ran into gale force winds off Point Conception - the "Cape Horn of the Pacific." The skipper put out the 28-ft. diameter C-9 parachute when progress against headwinds began to diminish. The strong coastal current that flows northward hereabouts caused the para-anchor to tow the big catamaran upwind! Because water is some 800 times heavier than air, large sea anchors should be used with caution where there are local currents, especially in close quarters. The sea anchor will pull the boat with the current, regardless of the intensity and direction of the wind. If the current is going your way, then fine and well. If not, be warned that the sea anchor may tow your boat over a ledge, across fishing nets, a shipping lane or into other hazardous areas. Transcript:

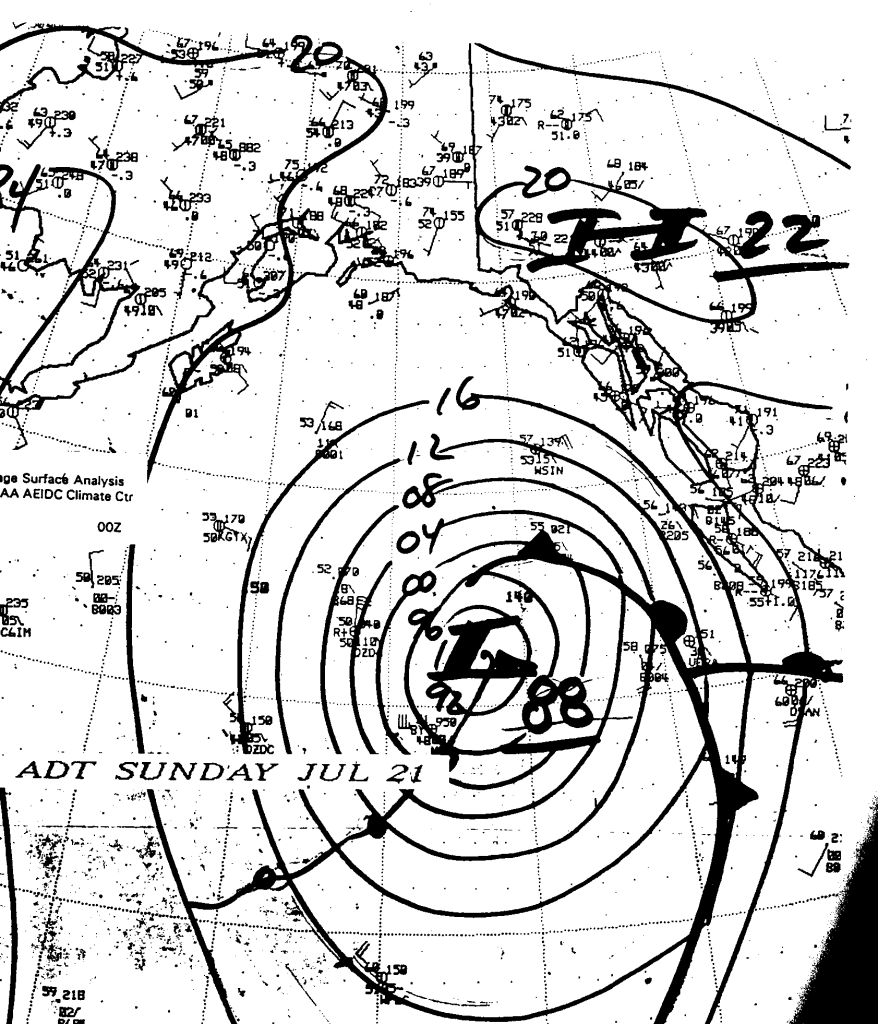

We were conducting sea trials of our newly launched C/S/K designed catamaran. We had departed Newport Beach on 9 June 1984 with the intention of making our way north to Vancouver B.C. On the evening of June 11 we anchored at Coho, an open roadstead just southwest of Point Conception, along with six or seven fishing boats and two other cruisers. The winds were northwesterly at 28 knots, gusting to 38 knots, and the seas were about 15 ft., which continued to build during the night. By early dawn the fishing vessels all departed in the direction of Santa Barbara, along with one of the cruisers. The other cruiser, a Westsail 32, raised sail and headed out to sea. At around 5:30 am we motored out to see what the conditions were... the 2 am weather report was 35 knots gusting 45, with seas of 15-21 ft. We continued on course for about an hour and a half when the wind shifted to the north by northwest and our progress began to diminish. The Westsail 32, under sail and engine, passed ahead of us on a port tack and seemed to be taking a lot of green water. Standing on our cabin top my eye level is about 18 ft. above the waterline and in several of the troughs I could not see over the approaching wave. The 6 am report described the sea as 18-26 ft. and I am sure they were all of 18 and occasionally 26 ft.

Within one mile or so of Point Arguello, the Westsail 32 turned and ran back toward Point Conception.... Though we were not in any trouble, we decided to deploy our 28' diameter parachute and take a rest. We had covered only nine miles in about three and a half hours. My windspeed indicator averages out most of the gusts, so the peak winds are not known, but while lying to the parachute the wind rarely fell below 40 knots, and on occasion we saw 50 knots.

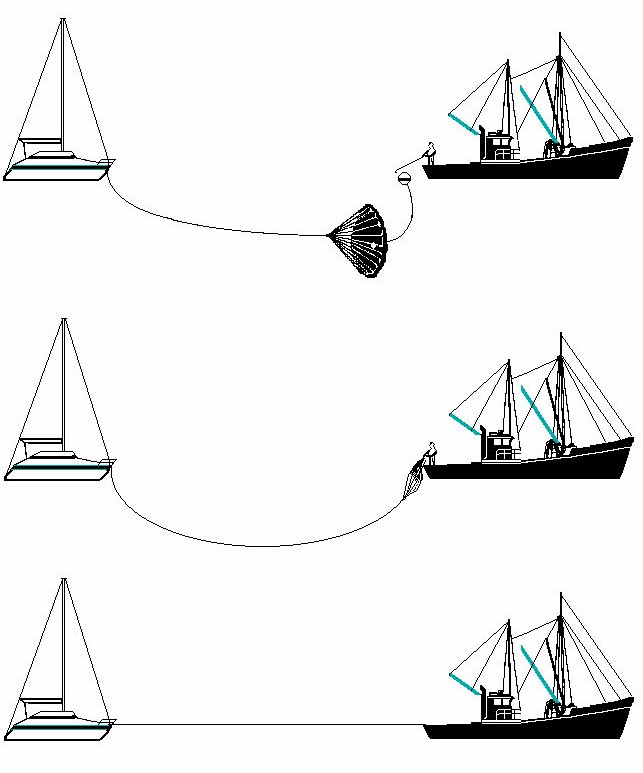

Standing about a mile and a half offshore, lying abeam to the sea under minimum power, we slowly deployed the parachute off the port bow, letting it stream off to weather about 30 to 40 feet. We then snubbed off the rode and watched the chute fill and come to full shape. We then fed out the rode until it was a full 500 ft. out to windward, then secured it to the bridle, in turn secured to the port and starboard bow bollards. Everything became quite peaceful. We took reference sights on the shoreline and went below for breakfast.

About twenty minutes later, I checked on our shore marks but could not identify them. I had a feeling of confusion and together with a crew member established a new set of reference marks on shore. Fifteen minutes later I went on deck and saw that the marks had shifted unexpectedly. What had confused me on my first sights was that I had expected our drift to be to leeward. After careful calculation we estimated that we were making about 2 knots to windward! We were making about the same progress to weather as we had been making motor-sailing, however, with everything shut down life had become so peaceful we had to refer to the windspeed indicator to verify the winds had not decreased and in fact had increased slightly.

After about two hours we decided to practice picking up the parachute and attempted a hand over hand retrieval. A bit of foolishness. We then cast off the rode and began to motor up on the trip line float. Again another bit of foolishness. The float's relationship to the parachute was impossible to determine and in short order we had the parachute around a prop. After recovering all the rode and what we could of the parachute, we sailed off back around Point Conception. So far as we could determine, our cat has never shown any tendency to sail about while laying to a parachute (on 500 ft. scope). Whatever movement there may be is within a five degree arc. If the movement is in fact greater than that it is very difficult to identify it from the other motions, created by the sea state.

All my parachute retrievals since this event have been by a polypropylene trip line, however I find even with the help of various crew members recovering a chute on 500 feet of rode is always work, even when conditions are less hectic. So far as I am concerned, getting to port ahead of a storm is the best tactic. But if that is impractical, lying to a parachute on a bridle, head-to-wind, or even with the sea quartering, is by far the safest and least wearing storm tactic I have tried to date.

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!