Canoe, "Tilikum" (Voss)

32' x 1.5 Tons

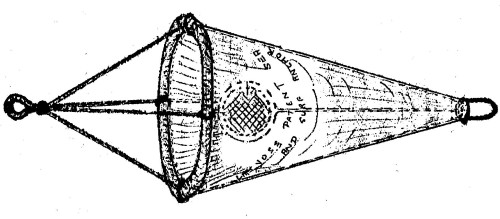

22" Dia. Cone Type Sea Anchor

File S/M-1, derived from the writings of John Claus Voss and Norman Kenny Luxton - Vessel name Tilikum, converted Siwash Indian war canoe, hailing port Victoria B.C., LOA 32' x Beam 5' x Draft 36" x 1.5 Tons - Sea anchor, four-foot long, 22-inch diameter canvas cone used in conjunction with a mizzen sail - Deployed in numerous storms during voyage from Victoria B.C. (May 19, 1901) to Tahiti, Australia, South Africa, and finally England (September 2, 1904).

This is one of the earliest recorded cases of a small sailing vessel using a sea anchor to negotiate heavy weather offshore. Mention of the use of the device is made in The Venturesome Voyages Of Captain Voss and Luxton's Pacific Crossing (Gray's Publishing, 1968 and 1971). Both books have been out of print but Grafton Books has recently issued a reprint of the former, now entitled Venturesome Voyages, in its "Mariner's Library" series.

Little is known of the life of John Voss, the father of drag devices. He was born in about 1854, some say in Newfoundland, others Nova Scotia, and yet others Sweden. His seafaring life seems to have begun in 1877 when as a young man he went to sea in large sailing vessels. By 1901 he was a hardened seaman, having served as master on many sailing ships plying the fur trade from Victoria to Yokohama. Much controversy surrounds him in his later years. Some maintain that he was eventually lost at sea. It is more likely, however, that he died in San Francisco in 1922, while earning a living driving a bus there.

The vessel making the remarkable 1901-1904 circumnavigation was a converted 32-ft. Siwash Indian dugout which, according to her owner, had been in many Indian battles on the West Coast of British Columbia. She was given the name Tilikum, a Chinook word meaning "friend." During the voyage to the South Pacific the crew of the Tilikum consisted of John Claus Voss, captain, and Norman Kenny Luxton, mate. The two later fell out with each other. Voss's attitude toward the sea was a very conservative one. He was not one to take anything for granted out there and dealt with the unpredictable forces of nature in a cautious, methodical way.

Wrote Norman Luxton, "Voss's ideas were very much more scientific in weathering a storm... he knew his business, and he learned it by going easy. I only once ever saw Voss take a chance. He never gave a storm any benefit of any doubt, and he never sailed until he even lost a sheet, always anticipating trouble. Many's the hell he has given me for not taking in sail when perhaps I should have." (Luxton's Pacific Crossing.)

Voss told Luxton about how he would heave-to in a storm on what he called, a "sea anchor." He had gotten the idea from an old sailor in the North Sea. Tilikum's sea anchor consisted of an iron barrel hoop about twenty two inches in diameter, with a four-foot canvas cone sewn on (see image).

It was used in a total of sixteen heavy gales during the three year circumnavigation. To quote Luxton, "Once, for seventeen days the Tilikum rode to such an appliance and a drag, and never shipped a cup of water. The weather was composed of samples of everything that the misnamed Pacific could put up."

Voss maintained that a stationary hull was better able to retain its buoyancy - rise to the seas. The same hull moving at speed through the water, he argued, was "held down by suction" and susceptible to great damage by boarding seas. In Venturesome Voyages he appendixed some twenty paragraphs of advice, where we find the following:

I will go a little further, claiming - and I have absolute confidence in doing so - that on no occasion while in charge of a vessel which was hove-to under storm sail in a violent gale, have I shipped a sea that caused any damage to ship or outfit, even though the storm sails had been carried away by the force of the wind. And the same applies to the small boats I have sailed on long cruises when they were hove-to under sea anchor and riding sail. (Venturesome Voyages, Grafton Books, 1989.)

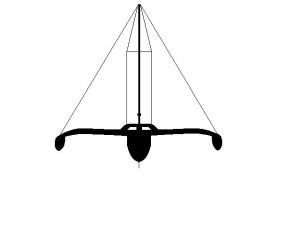

Voss's philosophy was to go into a defensive posture - heave-to - long before the seas built too high or began breaking. Head sails were first dropped and the vessel made to head up into the seas. The sea anchor was then lowered and its cable let out. The heavy mizzen was then set as a riding sail. Thus, if the bow fell off to one side it could only yaw so far before the sea anchor and the mizzen brought it back to face into the teeth of the gale. Using this tactic, Voss and crew were able to survive a 1912 typhoon off the coast of Japan in Sea Queen, a little yawl, 19 feet on the waterline! The outer fringes of the typhoon lifted the roof off Yokohama Station and drove a large steamer ashore.

This idea of "a cone and a riding sail" has entered into the folklore of heavy weather tactics. To this day your authors receive inquiries about the so-called Voss method. Both the Coast Guard report (CG-D-20-87, Investigation of the Use of Drogues to Improve the Safety of Sailing Yachts) and the Wolfson RORC report have concluded that small, cone-type sea anchors are generally ineffective and unstable on their own. Both indicate the need for larger devices for use off the bow.

Earl Hinz renders a similar verdict in Understanding Sea Anchors And Drogues (Cornell Maritime Press, 1987). It has to be pointed out, also, that small conical sea anchors tend to put inordinate strains on rudders and their fittings as well.

Lin and Larry Pardey have modified and modernized Voss's method of heaving-to with great success on their own boats. They have replaced Voss's small conical sea anchor with a larger parachute-type device, and his canvas mizzen with a modern storm trysail. Using these they have ridden out various storms with success - see Files S/M-3 & 4.

In 1965 Tilikum was restored and moved into the Maritime Museum of British Columbia in Victoria's Bastion Square. She - and her crude drag devices - can be seen there today, along with some other famous sailboats, among them John "Hurricane" Guzzwell's Trekka. A fact-finding mission to the Maritime Museum of British Columbia is highly recommend (read good excuse for a wonderful little vacation).

From Seattle take the high speed ferry to the delightful port of Victoria, then relax and immerse yourself in the sights, sounds and smells of a seafaring past. Stand on the wharf, close your eyes, and you may imagine that you hear the clanging of ship's bells and the noise and commotion that surrounds the arrival of a big, three-masted bark, after a difficult passage from Yokohama. The gaunt, tired Captain Voss leans silently over the rail. The first mate shouts orders as men with salt-crusted beards furl and tidy sails from their lofty perches up in the sky. Waiting on the wharf are the wives and children of the seamen, dressed in the attire of the late 1800s. A seagull cries out. The last yardarm is secured. The ship coasts to a perfect docking. Lines are heaved ashore. If you press your imagination a little more you may even see the horse-drawn carts lined up on the wharf, the horses flicking their tails impatiently.

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!

D/T-5

D/T-5