D/C-9

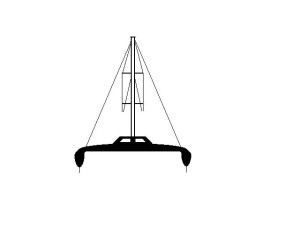

Catamaran, Searunner

44' x 25' x 6 Tons

Shewmon VP and Shewmon 9-Ft.

Severe Tehuantepeccer (Hurricane-Force)

File D/C-9, obtained from Captain Fred Yeates, Tarpon Springs, FL. - Vessel name Anna Kay, hailing port Gwenn Island, VA, catamaran, designed by Jim Brown, LOA 44' x Beam 25' x Draft 3' x 6 Tons - Drogues: 4-ft. diameter Shewmon Variable Pull & 9-ft. diameter Shewmon (sea anchor) on 250' x 3/4" nylon braid tether, with bridle arms of 25' each and 5/8" galvanized swivel - Deployed in a severe Tehuantepeccer storm in 160 fathoms of water in the Gulf of Tehuantepec with winds of 120+ knots and seas of 40 ft. and greater - Vessel was blown 100 miles offshore in 20 hours before having to be abandoned.

Situated on the Pacific side of the Mexican isthmus, the Gulf of Tehuantepec ranks among the most perilous bodies of water on the planet earth. Experienced ship captains fear the Tehuantepec as they fear Bengal monsoons, Caribbean hurricanes, North Atlantic icebergs, North Pacific fog and the freak waves of the Agulhas (see a list of such events by month in Appendix V at the back this publication).

Crossing the Gulf of Tehuantepec is not something to be trifled with. The weather mechanism that can generate 70-knot winds in a matter of hours can be likened to a boiling kettle from which high pressure steam has only one escape route - the spout. The kettle is the Gulf of Mexico, flanked by the Mexican Plateau and the 10,000 ft. Sierra Madre mountains.

The steam consists of the northeast tradewinds reinforced by a massive high pressure cell situated over Texas or thereabouts. The spout is the cut in the Sierra Madre Mountains (in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec) through which the wind blasts out into the Pacific.

The Tehuantepec Demon (as locals refer to it) is most active in the months of November, December and January, though it has been known to wake up in other months. The demon's reach may extend a few hundred miles out to sea.

In crossing the Tehuantepec most southbound cruisers hold up in Huatulco Bay, waiting for a weather window. Northbound cruisers do the same on the other side of the Gulf of Tehuantepec, in Puerto Madero. The distance between Bahia de Huatulco and Puerto Madero is 260 miles as the crow flies

Since a strong wind must blow over a minimal distance - fetch - in order to build dangerous seas, and since the Tehuantepeccer blows from land out to sea, standard procedure - the highly recommended course - is to hug the beach and anchor if the Tehuantepec awakens, using the boat's heaviest ground tackle. Note that in doing so there are currents and other hazards that have to be watched for.

Captain Fred Yeates built Anna Kay with his own hands in 1984. She was the largest Jim Brown designed catamaran at the time. He spent five years cruising the Caribbean before transiting the Panama Canal in the spring of 1991. After several years in San Diego, Yeates sailed up to Santa Barbara where Victor Shane briefly met him. In the autumn of 1995 Yeates and Holly Janette Gatioan set sail out of Santa Barbara. Their destination was to be the Caribbean, via the Panama Canal. They spent several months in Mexico, arriving in Huatulco Bay in late February. Anna Kay waited there for two weeks. On 5 March a 48-hour window came through from the Canadian route forecaster Herb Hilgenburg via SSB. The weather fax was good and the port captain predicted safe sailing for two days. Fred and Holly set off to cross the Gulf of Tehuantepec and a nice warm breeze pushed them past Salina Cruz that night. The next day the wind freshened and Anna Kay was moving along at a nice clip, hugging the beach just in case the Tehuantepec should awaken. In the afternoon of 7 March 1996 the Tehuantepec awoke with a vengeance. The wind did an abrupt right-face and started blowing offshore, building to hurricane force in two hours, wiping out the local fishing fleet and claiming dozens of lives. Anna Kay was blown offshore. Transcript:

We were sailing off the Mexican coast, on the Pacific side, in the area known as the Gulf of Tehuantepec. At 1500 hrs on the afternoon of 7 March 1996 I found myself staring at a true wonder of nature - the largest thunder cloud I had ever seen, grow and form into a massive solid black wall of wind and rain bearing down directly on Anna Kay. I awakened Holly from her sleep. She came up on deck and saw what was coming down. I can't repeat her first words. The cold wind and rain hit us like a sledgehammer. There were other vessels around us, large shrimp boats, with crews of four or five. We watched them struggle with the sudden buildup of wind and sea.

Anna Kay was handling the conditions very well, the wind pushing us along the beach in the direction we wanted to go, there being no reason to anchor. In fact, by then it would have been quite difficult to do so. The bottom was too deep and the surf along the shore already quite spectacular. The wind continued to build. As we were being blasted down along the shore we witnessed one shrimp boat capsize. Clearly others were in trouble as well. With darkness falling, conditions worsening, and having no radar, I felt it would be wise to move offshore. Around 2000 hrs the wind suddenly shifted 90° and quickly built up to 75 knots! I deployed my 4' Shewmon VP [variable pull] drogue. Holly and I watched the last shore light disappear. We were now alone and heading out to sea.

With the drogue deployed from a stern bridle the behavior of the boat was relatively comfortable and I was able to lie down and rest for an hour or so. By midnight the confused seas had built to such an extent that the ride was getting scary. Suddenly we started moving faster, crashing-banging sounds all around. We came on deck and discovered that the drogue had twisted and tangled itself. I retrieve it, straightened it out and re-deployed it. The behavior of the boat improved. Around 0300 the drogue fouled again. In the darkness I couldn't tell why. It was a vital piece of gear and it had always worked before. About all I could do was to haul it back in and try re-deployment.

Dawn revealed an ugly sea. As the sun came up the wind increased, and with it came even larger seas. Once again the drogue fouled and I hauled it in, with Holly at the helm. By now the wind was gusting to 100. With no drag in the water we started to be picked up and thrown about by huge confused seas, cresting on both sides and to the rear. I went below and hauled out my 9-ft. Shewmon sea anchor. Everything was a mess down below, with water sloshing about my ankles. With quiet a bit of difficulty I set the bigger sea anchor [off the stern, on the fly] and breathed a sigh of relief when it opened and held. With the big Shewmon deployed the boat slowed down and I didn't have to steer. I could leave the helm and actually go inside. I felt like resting for a while. But that was not to be. A wave washed the dinghy overboard. It was still tied and being dragged ten feet behind Anna Kay (the sea anchor being some 250' behind the boat). Big waves were breaking over our transom, trying to throw the dinghy at the catamaran. I thought about letting the dinghy sink and provide more drag. But the next wave convinced me otherwise. The dink had to go. I crawled to the transom with a knife in my teeth and cut it away.

The wind was still increasing. As we rose to the top of a wave the sea was a white-out all around. The sea anchor was getting rolled by the steep, confused waves, from the left, then from the right. Later, as I was watching, it got caught by two cross-seas and collapsed right before my eyes. I worked very hard to retrieve it, with Holly at the helm, trying to keep the boat from broaching. The sea anchor was all tangled up but not torn. I untangled it, only to have a wave come along and tangle it again and almost sweep me overboard. After straightening out the sea anchor I carefully deployed it, trying to let it out as slowly as possible. It worked fine again for a while, before being fouled by more cross seas. I had no choice but to pull it back in again. This took some doing. The 3/4" rode was slippery and my hands were all white and wrinkled by now. My safety harness saved me many times. I felt the problem was not having a swivel. Dan Shewmon himself had told me that it was not necessary. But in this situation it was. In the chaos down below I found my heaviest ground tackle swivel. I hooked everything up - not an easy task. It took a little time. The wind was gusting way past 100 now. The gusts were so powerful that they would flatten the sea by the acre, whipping up spray that would white-out the entire ocean. I heaved the sea anchor overboard again. As I tried to ease the line out we surfed down a huge wave and I lost control. We were surfing at 15 knots. I had to let go the rope. I had to get my feet out of the way of the lines that were running out. The line reached its end and stretched. The sea anchor opened, a beautiful sight. Then it shuddered, turned into a rag and disappeared.

We had lost the sea anchor. I sat down next to Holly and kept yelling "what happened?" But this was not the time or place to cry over spilt milk. When I retrieved the rode only one new shackle was at the end [the connecting eye of the 5/8" galvanized swivel must have broken]. I hooked up the 4' drogue and put it out again. Again it helped some, but didn't last long and I had to retrieve it. It was badly torn now and we couldn't tell what it had originally looked like. I asked Holly if she could sew it up. She went below looking for the sewing kit. I then put out a tire, and a couple of anchors to slow us down. I went forward and struggled with our largest anchor, trying not to look at the waves crashing all around (hope never to see such a sight again). I trailed as many things as I could off the stern to create drag and it helped a little bit. I seem to remember we managed a drink of water or juice then. I also remember seeing birds that couldn't fly, and turtles in great distress.

Late afternoon. Night was coming and there would be no moon until midnight or later. It was very cold. I had put on my Mustang immersion suit earlier, but it was open at neck, sleeves and ankles, so I was soaking wet and shivering. Holly was no better off as we screamed our commitments to each other above the noise of the wind and encouraged each other to fight on. The poor boat was trashed inside, but structurally sound. We would surf down a wave, be lifted to the top only to be sledge-hammered sideways by a cross sea. This action would launch heavy things around inside, levitating them, then causing them to hit something hard when the boat moved again. At the helm it was hang on for your life as white water tried to sweep you clean off the deck. The boat would be lifted by a crest, the bows would hang in mid-air and teeter there, before dropping one way or the other. Going over the back was much better than surfing the front, but you had to be ready for both.

Holly saw it first, pointing straight ahead, yelling "A freighter! A freighter!" It was half a mile away, a big white freighter, her bow scooping a huge sea, the wind whipping the water into a rainbow of spray that went clear over the bridge. The poor freighter looked like a canoe in the rapids. I went below and called on the VHF. I tried three times. No response. Finally they came back. I talked with the captain. He said the weather report was for conditions to get far worse. I was concerned about our lives. I was concerned about Holly. We truly love the life style, the people, the fun and the freedom of cruising, but we weren't out there to commit suicide. I issued a formal mayday. The captain of the freighter said he would try to make a lee.

I went down below. There was no time to gather the treasures of a lifetime, clothes, books, charts, photographs, things that can never be replaced. My wallet washed past my ankle. I picked it up, put a few other papers in my backpack and went out on deck. Holly went below to put a few things in a bag. The freighter passed by and came around behind us. Its towering bow came right on top of us, stopping in the nick of time. I saw her name, CHIQUITA BARU. We slid by and they fired rocket lines. But the wind blew them right back at the freighter. I asked Holly to cut away all the things we were dragging in the water. She was almost washed away in the process. It seemed that conditions were getting worse by the minute. I could see that the freighter was having its own problems, rolling dangerously, heavy surf crashing on deck as it lay broadside to the wind.

Anna Kay's motor started right up. The rudders worked fine. I tried to hold position by motoring around. Impossible. I tried reverse. No good. The freighter made another pass close by behind us, firing rocket lines that just got blown away again. We turned again. They were putting cargo nets over the side. Somehow we managed to come alongside. The catamaran's stable platform made it easier to get off. There was only time to help Holly up the ladder. She was alive, and that was all that counted. The ladder was swinging in and out, banging against the side of the huge hull. I urged her on, "climb, baby climb," and jumped myself. I got her moving up to strong hands that were waiting at the rails. She was taken below immediately, the conditions even on the deck of this Norwegian freighter being dangerous. The lines of the Anna Kay were let go and she drifted away. My last sight of her was a huge wave crashing over and onto the bows. She shook it off, and rose to the next, and then seemed to disappear in the stormy night.