S/C-5

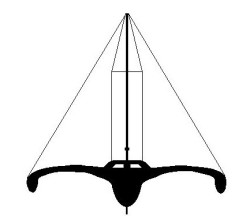

Catamaran, Walter Greene

50' x 30' x 5 Tons

4-Ft. Dia. Sea Anchor

Force 9 Conditions

File S/C-5, obtained from Walter Greene, Yarmouth, ME. - Vessel name Sebago, catamaran, designed by Walter Greene, LOA 50' x Beam 30' x Draft 7' (20" board up) x 5 Tons - Sea anchor: 4-ft. Diameter Shewmon on 250' x 3/4" nylon braid tether and bridle arms of 50' each, with 1/2" galvanized swivel - No trip line - Deployed in a whole gale in deep water in the middle of the North Atlantic with winds of 40-50 knots and seas of 25-30 ft. - Vessel's bow yawed 45-60° - Drift was estimated to be 30 n.m. during 48 hours at sea anchor.

By way of a brief digression we should perhaps mention a previous experience of renowned multihull designer Walter Greene, an experience that ushered in a new era in SAR (search and rescue). Indeed the experience marked a point in maritime history when it became possible to ensure the safety and survival of human life at sea to an extent never before possible.

On 10 October 1982 Greene was sailing his 50' trimaran Gonzo to St. Malo, France, when it capsized in a violent North Atlantic storm 300 miles south-east of Cape Cod. The boat had been running before 30-ft. seas without a drogue when she was picked up and thrown by a huge wave - she broach-capsized when one of her bows dug into green water. Once over the initial shock of the capsize, Greene and his well-prepared crew jumped into action. In no time they had donned their immersion suits, lashed themselves to the upturned, floating, hull, and switched on the EPIRB - Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon.

It was the navigation officer on board TWA's flight 904 that first heard the lonely wailing of Gonzo's EPIRB (the signal is swept audio tone, sounding like a miniature "wow-wow" police siren). The information was immediately relayed to the FAA's Oceanic Control at Islip, New York, which in turn informed Atlantic Rescue at Scott Air Force Base in Illinois.

At that time (1982) SARSAT - Search And Rescue Satellite-Aided Tracking - was not quite operational, but a participating Russian satellite, Cospas, was known to be overhead. Scott AFB obtained an uplink and sure enough, no sooner had Cospas signed on than it confirmed a "hit." The satellite then provided data and telemetry needed to pinpoint the position of the distressed vessel. Atlantic Rescue then broadcast an urgent All Ships Bulletin, and the tanker California Getty was diverted to the scene. At the same time, the Coast Guard Air Station at Elizabeth City North Carolina was briefed and advised to launch a C-130 search plane, which picked up Gonzo's EPIRB signal, homed in on it and dropped two datum marker buoys (which transmit additional homing signals on a different frequency).

The tanker California Getty was the first on the scene, but failed to effect safe rescue in the 25 ft. seas, standing off to windward to provide a "breakwater" for the disabled trimaran. And there she stayed, "like a big Saint Bernard," until the 210' Coast Guard Cutter Vigorous arrived on the scene.

One by one the three survivors were taken off to safety, concluding one of the most remarkable rescues in maritime history -one of the first in which a satellite played an instrumental role. (A quick reminder that SARSAT is now fully operational in most areas of the world and any sailor with a Class A EPIRB can access the grid to get a distress signal through to international Search & Rescue agencies).

Walter Greene happily went on to design many more multihulls and four years later used a sea anchor on board his 50' catamaran, the infamous Sebago. The 4-ft. diameter Shewmon sea anchor was deployed off the bow, but was too small to do a satisfactory job (the same sea anchor did a lot better when used off the stern - see file D/C-1.) The bows of the big catamaran yawed past 60° at times.

Shewmon sea anchors are available in many sizes, up to 33 feet in diameter. Literature published by Shewmon, Inc. would seem to indicate the need for an 8-10 ft. diameter Shewmon sea anchor for a boat the size and weight of Greene's Sebago.

Why did Walter Greene choose a 4-ft. diameter sea anchor instead? Likely he was worried about a bigger one being too "unyielding." Victor Shane ran into this same apprehension among other multihull sailors. To this day some of them will react with alarm at the very idea of tethering their boats to a large diameter, "unyielding" sea anchor in a gale.