S/P-1

S/P-1

Commercial F/V

50' x 22 Tons

28-Ft. Dia. Parachute Sea Anchor

Force 10 Conditions

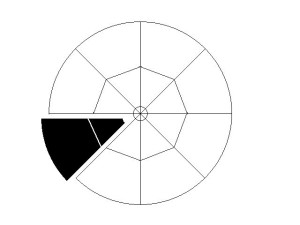

File S/P-1, obtained from Captain Arthur Davey, Yarmouth Port, MA. - Vessel name Sea Roamer, hailing port Hyannis, MA, commercial F/V, designed by Gallagher, LOA 50' x LWL 48' x Beam 16' x Draft 6' x 22 Tons - Sea anchor: 28-ft. Diameter C-9 military class parachute on 150' x 3/4" Poly-Dacron rode with 5/8" galvanized swivel - No trip line - Deployed in a storm in shallow water (60 fathoms) 75 miles east of Chatham, Massachusetts, with winds of 50 knots and seas 20-30 ft. - Vessel's bow yawed 10° - Parachute disintegrated after 20 hours (probably due to short, low-stretch rode).

This file was derived from numerous telephone conversations with Captain Arthur Davey, along with an article called The Wreck Of The Sea Roamer by William P. Coughlin of the Boston Globe (courtesy Boston Globe).

At the time, Captain Arthur Davey was a 30-year veteran of the commercial fisheries. He has been through more storms than he can remember. This one was different, however.

On the night of Tuesday 15 December 1981, Sea Roamer, a steel-hulled gillnetter out of Hyannis, was about 75 miles offshore, riding to her 28-ft. diameter parachute in 30-knot winds. The rode consisted of about 150 feet of 3/4" low-stretch Poly-Dacron. The barometer was dropping. There were warnings of two weather fronts, with an interval of 12-18 hours forecast between them. A faster moving upper altitude TROUGH was about to overtake and reinforce a surface LOW (classic "bomb" type storm development, similar to Fastnet '79.)

By 8 a.m. the next morning it was blowing 45 knots as Sea Roamer's bow, snubbed to her parachute, lifted in what now were 30 ft. combined seas. One and a half hours later it was blowing 50 knots - with 90-knot gusts recorded at Chatham Weather Station.

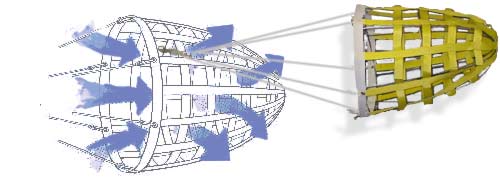

The 150 feet of Poly-Dacron rode was not long enough, nor did it have sufficient elasticity to absorb the dynamic loads imposed by the wind and the seas on the 22-ton commercial F/V. Those loads were being transmitted directly to the lightweight surplus parachute in the water, and it began to fail - panels began to blow out.

Sea Roamer's bow began to swing off the wind in an increasing arc. The parachute finally disintegrated and Captain Davey had to cut away its remains. Sea Roamer came beam to the seas and began rolling heavily, rails buried. The skipper fired up the engine and put her on a westerly course, the 300 horsepower Caterpillar Diesel chugging at 1200 RPM. That was when the two weather fronts came together. They fell into synch, "Right on top of us," Captain Davey said. No 12-18 hour interval. No window of escape for Sea Roamer. The forecast had been wrong.

The seas rapidly built until some of them started to curl over and break. Arthur Davey was at the helm, trying to call them. He had to steer carefully, using Searoamer's bow as a shield. When he saw one coming he would head into it by putting down the wheel and easing off on the throttle. The wave would slam against the bow, making the hull pivot on its CLR. The skipper would then apply throttle again, inching westward, rounding up north to parry off another wave, then inching westward....

Captain Davey: "Once in a while, one would break over the bow, but I wasn't concerned. I had been caught in it before. And, if worse came to worse, I figured we could go further to south'ard and go in the deep water route by Great Round Shoal Channel."

An hour later the wind was screeching at hurricane force - 75 miles per hour sustained. The sea had become white with foam and was now delivering hammer blows at Sea Roamer's steel hull.

Already the Coast Guard had its hands full. For that was the dreadful night in which the 94-ft. F/V Pioneer went down and all hands had to be rescued. Meanwhile, Marjorie and Arthur Davey Sr., the skipper's parents, had been calling Sea Roamer over the base station from their home at South Yarmouth - to no avail. Their concern mounted until finally a call was put through to the Coast Guard. Soon they were listening on Channel 16 as the Coast Guard station at Chatham put out its own calls: "Come in Sea Roamer. Come in Sea Roamer." There was no answer.

Sea Roamer, apparently out of range, continued to inch her way through streaked, white mountains of water until 3:40 in the afternoon. That was when the hands on the ship's clock stopped - a watery giant, coming from a different direction, curled and exploded right on top of her.

"It was a rogue. A rogue wave of good proportions," Captain Davey said later, "I was at the wheel. I was on watch. That's all I remember to this day. How it hit, I don't know. I can vaguely remember the chopper, then the brain scan machine at the hospital. That's about it."

The wave ripped open and devastated Sea Roamer's heavily built oak and plywood wheelhouse. It also knocked the skipper unconscious. According to Roy McKenzie, mate for two years, "Everything was blown out in the wheelhouse. The captain was on the floor... the doorway was gone. Blood was pouring out of both his ears, his forehead and mouth. His eyes were open, rolled back."

Somehow McKenzie and deckhand Jack La France managed to get the unconscious Arthur Davey into a survival suit, and then put their own suits on. Sea Roamer lay dead in the water, with three of her five watertight compartments flooded forward. "The sea had gone to just foam. It was all white. Terrifying. You could hear the wind. That shrieking noise. That roaring," said McKenzie.

They deployed the life raft and struggled with it, but had to cut it loose, unable to put the unconscious captain in. The seas were now breaking regularly and Sea Roamer was lying a-hull, rolling heavily - up to 60°. Twilight descended. A tanker passed by, but didn't see the lights that they flashed at it - it was having troubles of its own. Exhausted, the men lay down on the steel deck next to their unconscious captain. Both recall having lifelike visions of their past lives.

By dawn the next day, the Coast Guard had a helicopter and a fixed wing Albatross out of Otis Field searching for Sea Roamer. On board the boat, Captain Davey suddenly groaned, opened his eyes, and looked around. "What happened?" he asked. "Get on the radio. Call the Coast Guard. And, Jack, Jeeze, will ya close the door. It's cold in here." There was no door to speak of - it had been blown away. The radio had been damaged - and the EPIRB lost - when the rogue wave hit. But McKenzie and La France bailed and managed to reconnect the battery line to the engine. They found the starter switch in the jumble of wires and hit it. The big diesel turned, stopped, turned again, caught and started to chug.

Sea Roamer was under way again, but her captain lapsed back into unconsciousness. The men steered for the west and kept bailing with buckets. At 12:39 p.m. on Thursday Dec. 17th, Lt. Steve Hilfery and co-pilot Lt. Ted Ohr, flying an Albatross seaplane out of Otis Field, spotted the little white hull of Sea Roamer in the rough sea below and a message quickly crackled back to the air station: "Located F/V Sea Roamer. Position, 41-dash-31 North latitude, 68-dash-50 West longitude, proceeding 330 degrees at five knots. Appears disoriented. There is damage to the pilot house."

The twin engined plane banked, turned and made a low-level pass over the boat. When the men heard the aircraft roar overhead they began sobbing uncontrollably. They came out and waved their hands.

At 2:55 p.m. a Coast Guard helicopter lifted the unconscious Captain Arthur Davey to safety, the seventh human life it had plucked from the ocean on that day.

At 2:55 p.m. a Coast Guard helicopter lifted the unconscious Captain Arthur Davey to safety, the seventh human life it had plucked from the ocean on that day.

The ordeal ended the next morning when the cutter Point Bonita eased into her berth at Woods Hole, having put three Coast Guard seamen on board Sea Roamer for the slow tow to Hyannis, and having taken La France and McKenzie on board the cutter for initial treatment for "harsh exposure." Roy McKenzie's wife Melody and his son, Roy Jr., were standing at the dock as lines were heaved to the Point Bonita. Jack La France stepped onto the concrete dock and made a vow never to go to sea again, a vow that he has yet to break.

But Captain Arthur Davey? Well, no sooner did he get released from the hospital than he was right back offshore, staring down another winter gale on the Georges Bank. For cryin' out loud Arthur.

How would Sea Roamer have fared at sea anchor if she had used 600 feet of elastic nylon rode instead of only 150 ft. of low-stretch Poly-Dacron? Would she have been able to ride out the storm without damage? We will never know, but Arthur Davey told Victor Shane that he was never too old to learn. He still uses parachutes at sea. But now with a long NYLON rode.

S/T-3

S/T-3