D/M 22

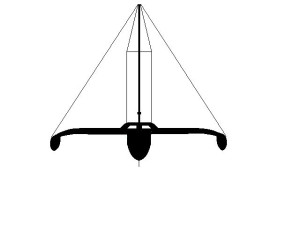

Dykstra-designed 2-masted

Aero Rigged Schooner.

Aero Rigged Schooner.

60' (18.5m) x 25 Tons, retractable centerboard

Jordan Series Drogue

Force 9+ Conditions

File D/M-22, obtained from Stephen Brown, France - Vessel name Novara, hailing port Newport UK, monohull cutter designed by Dykstra and built by Damstra in Holland, LOA 60' (18.5m) x Beam 13' 9" (4.5m) x Draft 5' 6" (1.7m) - 10' (3m) (CB down) x 25 Tons - retractable centerboard - Drogue: Jordan Series Drogue on 330' (100m) - 180 cones, spectra/dyneema double braid rode plus 25kg of chain for weight, using 10m bridle arms and 10m rode before teh first cone - Deployed in deep water en route from South Georgia to Port Stanley, Falkland Islands in winds of 45kts to 55kts with gusts over 60 kts and breaking seas of 16 - 23 ft. (5 -7m) - Speed was reduced to under 2 knots during 42 hours of deployment. Total drift was about 82 nm.

Steve Brown has over 80,000 miles of experience, and seems to like cold weather! Novara was custom built as an icebreaker specifically for high lattitude and polar cruising, so they knew they would be getting into some serious weather.

On trying to return to the Falklands after cruising around South Georgia they were unable to find a decent weather window so left immediately after a storm passed, hoping that the wind and the waves would abate over the following week.

They did, but only for a few days, after which another system passed through, bringing 45kts and breaking seas. Reluctant to be tethered to a para-anchor (which was probably too small), They elected to deploy the series drogue.

This was stored, ready to go, in a launch bag on the roof of the pilot house, with the end-weight chain in a separate bag at the stern near to the launch position. The bridles were already attached to the stern cleats and were temporarily secured using cable ties that woujld quickly break when a load was applied.

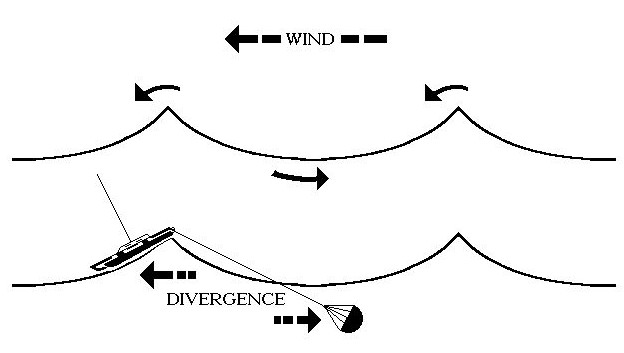

Once the decision to deploy was made, the chain and drogue were thrown over the stern. The centerboard was up. Once in the water, the boat quickly turned around to head downwind, and the speed slowed to under 2 knots. As Steve said, "it works!"

Although the boat lifted nicely on each passing wave, they did get pooped several times by breaking waves coming up over the stern and flooding the cockpit.

After almost two days the winds eased to 25kts and Steve and his crew were able to winch the drogue in using their main winch.

They lost a couple of days of time, and 82 miles of distance, but everyone was safe and there was no drama. Another successful deployment.

Steve makes a number of interesting points about his experience:

- Using a large sailbag secured close to the deployment point would have been easier than their pilothouse roof method.

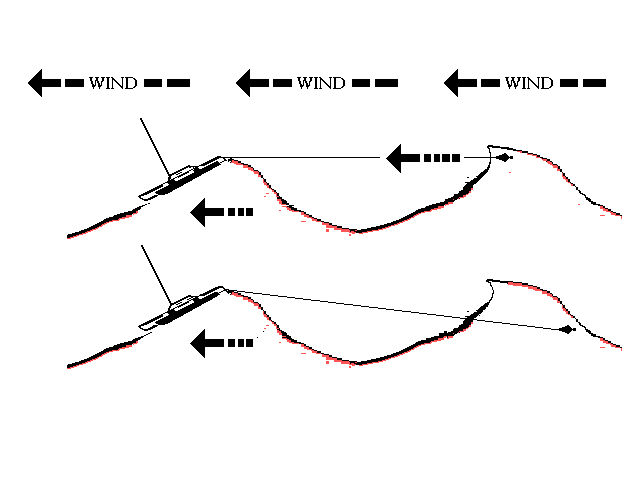

- On retrieving the drogue they found 14 cones had been shredded by the wind, having been lifted clear of the water. He has since replaced the cones and extended the first section (closest to the stern of the boat) by 10 meters so as to ensure they stay submerged.

- One of the bridles had been chafed through to 50% of its diameter through contact with a rough patch on the stern hawser. Steve has since put some thick diamter tubing over the bridle to try to prevent that.

- Retrieval could have been easier if the drogue had been led directly to the main winch instead of forward around a block and then back to the main winch. That would have avoided having a crew member at risk out on the side decks.

- Make sure your boat is ready for a huge wave crashing over your stern, as it can happen even with a drogue. Good cockpit drainage and well sealed hatches and companion ways are crucial.

- Practice makes perfect and will highlight any deficiencies in your setup or technique. Do this well before you set off on a passage so you can get it perfect.

To these observations, we can perhaps also add these suggestions:

- Chafe is a huge problem for drag devices that needs serious consideration BEFORE you set out to sea. The key to this is to avoid the bridle from touching anything. Steve's solution of using a big plastic hose around the bridle is a good one. Perhaps an even better solution is that described by Tim Good in the previous report D/M-21 Seastream 43 in which he installs a custom-built bridle attachment point that extends well aft of anything that could possible touch the bridle.

Then during the storm check on it regularly. Had Steve's storm lasted another day or two he could have had some big problems if the bridle chafed through. - Big seas can and will jump onboard into your cockpit - be prepared for that and make sure anyone outside, even in the cockpit, is securely tethered. Better still, stay below and get some rest.

- As Steve says, think through and practice the retrieval. The challenge is how to get started - how will you get the bridle on to the winch to begin the process?

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!