D/T-9

D/T-9

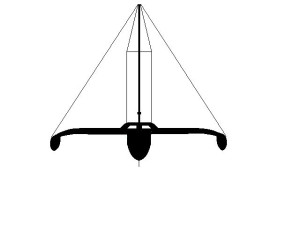

Trimaran, Shuttleworth

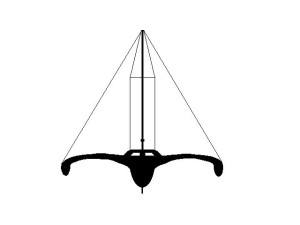

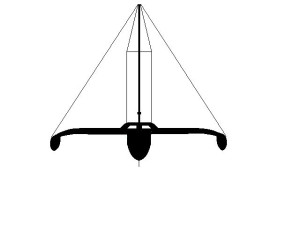

60' x 40' x 10 Tons

12 Knotted Warps (300' each)

Force 12 Conditions

File D/T-9, derived from an article by Richard B. Wilson, appearing in the October 1991 issue of SAIL MAGAZINE - Vessel name Great American (ex-Livery Dole IV, ex-Travacrest Seaway) hailing port Boston, MA, maxi ocean racing trimaran designed by John Shuttleworth, LOA 60' x Beam 40' x Draft 11' (3' board up) x 10 Tons - Drags: 12 knotted warps, 300' each (3/4" and 5/8" nylon) - Deployed in a 940 milibar storm in deep water 400 miles west of Cape Horn with sustained winds of 70 knots and breaking seas of 50' - Vessel capsized on 22 November 1990 despite the 12 long warps - Crew of two were rescued by the M/V New Zealand Pacific.

On 22 October 1990 Rich Wilson and Cape Horn veteran Steve Pettengill set sail on the 60-ft. maxi ocean racing trimaran Great American determined to break the 76-day San Francisco to Boston record set in 1853 by the clipper Northern Light. Apart from wanting to beat the record, it was also Rich Wilson's goal to heighten public awareness of the activities of the American Lung Association and to prove the viability of corporate sponsorship in sailing. Wilson is a severe asthmatic.

Sailing out of San Francisco Bay Wilson and Pettengill put "pedal to the metal" and tried to imagine their opponent, Northern Light, beginning to trail behind. Having records of Northern Light's daily runs, they had their imaginary opponent in view, so to speak, trailing behind all the way down the coast of California and then Mexico. In skirting hurricanes Trudy and Vance off Mexico, however, the lead changed hands a few times as the ghost of the 200-ft., three-masted clipper ship would overtake the trimaran, only to be later overtaken herself. Once past the equator, Wilson and Pettengill began bashing full bore into the southeast trade winds. The going was rough and took a heavy toll in equipment failures. After passing Pitcairn Island they began to line up their approach to Cape Horn - and "the mother of all storms."

It began as a low system that "exploded" (to quote the words of meteorologist Bob Rice) into a 940 milibar storm, with Great American's number written all over it. Approximately 600 miles from Cape Horn the storm said hello to Wilson and Pettengill when the trimaran broached, tripped on her big daggerboard, and Wilson was thrown violently out of his bunk. The two dazed men found that they had to raise Great American's huge daggerboard all the way up to improve steering and avoid tripping on it.

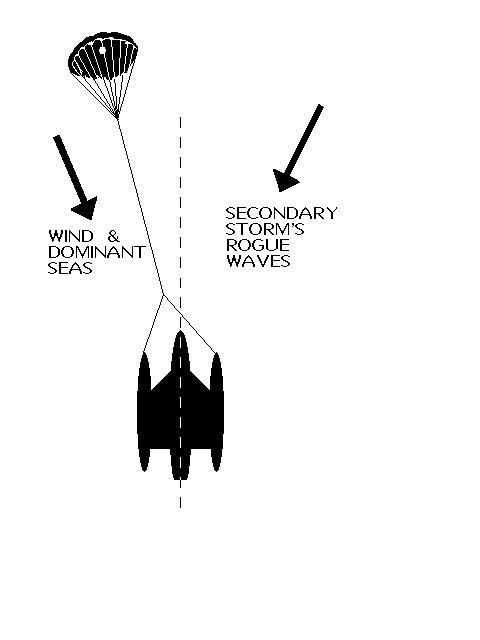

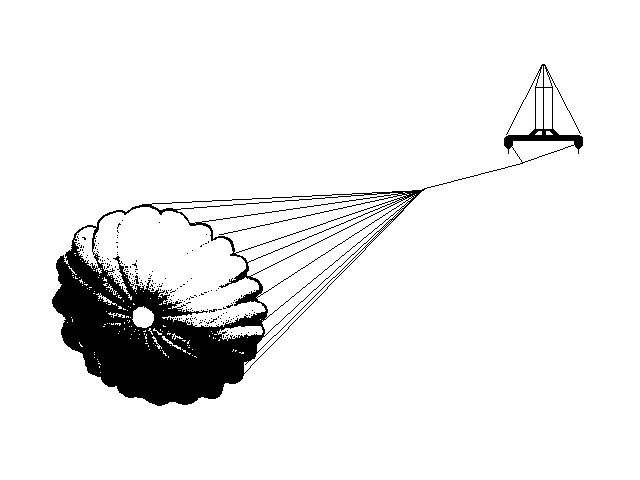

Steve Pettengill then let out five knotted warps, 300' each, slowing the boat down a little. On the next day the boat broached again with the five warps in tow. But she side-slipped smoothly - raising the board had definitely helped. Pettengill added three more 300' long knotted warps. On Wednesday morning, 21 November, the boat's barograph tracer hit rock bottom. Four additional knotted warps were then added, making a total of twelve (12) to bring the speed back down to 9 knots in 70-knot winds and 50-foot seas.

On Thanksgiving morning, some 400 miles west of Cape Horn, a graybeard swept over the entire boat (this trimaran is 60 feet long and 40 feet wide!) carrying away the two wind generators. Great American then rushed down another steep mountain. The combined drag of the twelve knotted warps were not enough to keep her properly aligned. She slewed to starboard, probably dug the port ama, heeled, and capsized. The two men, fortunately OK, immediately donned their immersion suits, activated the 406 MHz EPIRB, and resigned themselves to the business of survival. As they were sorting out the debris in the inverted main hull, "the grandfather of all waves wrenched the water-laden trimaran out of the water, spun her, and slammed her violently back down, upright again." (Quoting from Wilson's article in SAIL).

So, Great American was right side up again! But the mast and the rigging were in pieces on deck and trailing in the water. The cockpit was awash and the main hull looked like a submarine, with the winches at sea level. Everything was in shambles. Everything had broken free down below. They wondered whether they would have been better off if they had remained upside down. Somehow, in the freezing cold, they managed to sort things out and get a little hot nourishment. Meanwhile, Scott Air Force Base in Illinois had received a "hit" from the EPIRB. Additionally the ARGOS, which had gone off when the second wave righted the boat, had alerted a base in France, which alerted Atlantic Rescue. AMVER (automated merchant vessel emergency routing) then found the nearest ship to be the New Zealand Pacific. In a feat of brilliant maneuvering, Captain Dave Watt brought his 62,000 ton ship - the world's largest refrigerated container carrier - alongside the awash Great American at 3:30 am in the dark. With the 815-foot ship rolling severely, Captain Watt coordinated the throttles and bow thrusters with such precision that Rich Wilson and Steve Pettengill were able to step onto the rope ladders hung down from the cliff-like side of the ship. They were then taken inside, cared for, and taken to Vlissingen, Holland.

Three years later, Rich Wilson and his new crew mate, Bill Biewenga, set out again from San Francisco. This time Wilson accomplished his goal. On April 7, 1993, Great American II finally arrived in Boston, 69 days and 20 hours out of San Francisco, beating Northern Light's record by six days. Wilson is currently head of Ocean Challenge, an educational institution dedicated to linking classrooms all over the world with ongoing adventures. Ocean Challenge has an interesting web site that readers may wish to explore: www.sitesalive.com