S/C-20

Catamaran, Crowther

49' x 24' x 8 Tons

15-Ft. Dia. Sea Anchor

Force 8-9 Conditions

SW gale vs Agulhas Current

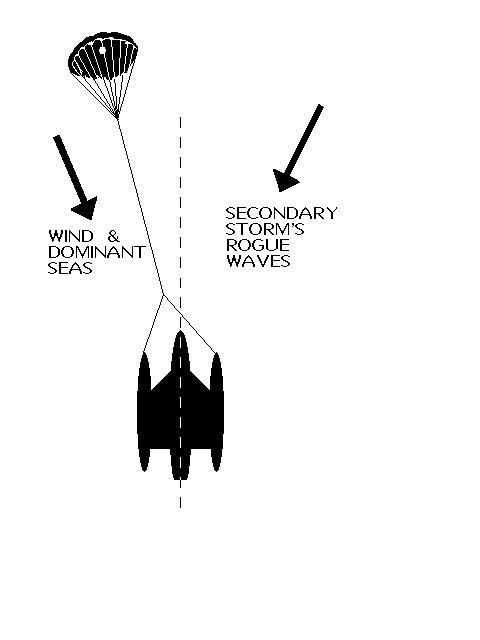

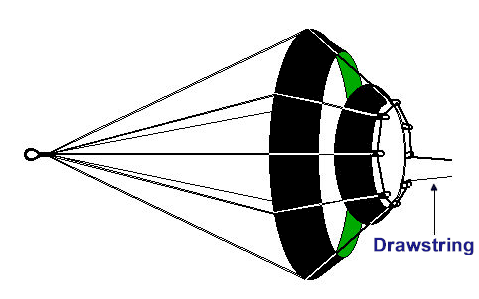

File S/C-20, obtained from Jean Claude Barey, Montreal, Canada - Vessel name Chasse Galerie II, hailing port Montreal, Spindrift catamaran, designed by Lock Crowther, LOA 49' x Beam 23' 6" x Draft 3' x 8 Tons - Sea anchor: 15-ft. Diameter Shewmon on 300' x 3/4" nylon three strand tether and bridle arms of 40' each, with 5/8" galvanized swivel - No trip line - Deployed in a whole gale in 500' of water about five miles SE of Port Elizabeth (South Africa) with winds of 40-45 knots and seas of 17-20 ft. - Vessel's bow yawed less than 10° - Drift was estimated to be 8 n.m. during 42 hours at sea anchor.

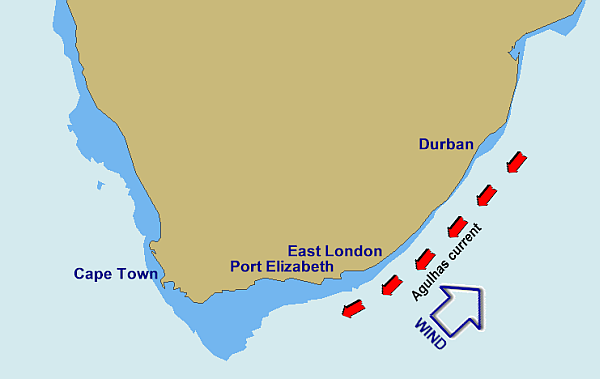

Jean Claude Barey took Chasse Galerie II on a circumnavigation in 1991. After transiting the Suez Canal he sailed her down to Durban, East London, Port Elizabeth, and was en route to Cape Town when he ran into a blow on the continental shelf, in close proximity to the Agulhas current. Transcript:

The conditions were not bad, but we could not take long tacks against the wind, because we were too close to the Agulhas current. We then used the sea anchor. Other boats without sea anchors decided to run back [to Port Elizabeth] after a few hours because they were not making progress to windward. Our Shewmon sea anchor worked well in those conditions. The boat was very steady (less than 5° yaw I will say).

The Gulf Stream and the Kuroshio (Japan) notwithstanding, the Agulhas is likely the strongest and most articulated current on earth - with a reputation for breaking ships in two. Because of it, the southeast coast of Africa represents a gauntlet that mariners need to run with great care and prudence. Charts of the region warn: "Abnormal waves of up to 20 meters in height, preceded by a deep trough, may be encountered in the area between the edge of the continental shelf and twenty miles to seaward thereof. These can occur when a strong southwesterly wind is blowing."

The Agulhas runs mainly from northeast to southwest, following the two hundred meter contour of the continental shelf and dissipating over the Agulhas Bank south of Mossel Bay.

If the Agulhas could be likened to a great river - moving 80 million tons of water per second at speeds of up to six knots - the high-crested waves that form on it during southwesterly storms would be akin to the tidal bores that travel up the Amazon and the Bay of Fundy.

Since the current extends to depths of more than 1000 meters, and since it generally does not intrude onto the shelf regions, but tends to lie just offshore of the shelf edge, evasive procedure for cruisers has always been to stay clear of the area seaward of the edge of the continental shelf. What many sailors do after leaving Durban is to sail offshore just far enough to "kiss and ride" the current south, but not so far that they can't make a hasty retreat out of its axis and duck inshore at the slightest indication that there is a southwesterly gale brewing.

As always, the cardinal rule is never leave according to clock or calender, nor have a deadline at the other end. According to literature forwarded to Victor Shane by Chris Bonnet, Principal of the Ocean Sailing Academy in Durban, the best time of the year to travel south is January to March.

The gauntlet from Durban to East London is 250 miles with absolutely no safe place to duck into in between. Bonnet advises sailors to wait for a favorable window. Leave Durban at the tail-end of a southwesterly blow when the barometer has topped out, preferably at about 1020 milibars. Clear customs and immigration at the advent of a southwesterly, which will normally blow from 36 to 48 hours, then sail on to the two hundred meter line as soon as possible as this is where you can obtain a several-knot boost from the current.

It also means that in the event of not reaching East London before another southwester, you can quickly duck inshore and avoid being caught in the middle of the current - where sixty foot walls of water have been known to break ships in two. You will find that on average the two hundred meter line will give you a distance offshore - between Durban and East London - of approximately ten miles.

The gauntlet from East London to Port Elizabeth is shorter - 120 nautical miles. Kiss and ride the current, move inshore if caught. The Port Elizabeth to Cape Town leg is a little safer as there are decent places to anchor or put into - Knyasna, Cape St. Francis or Krombaai. But watch the charts and proceed with caution as there are rocks and reefs all about.

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!