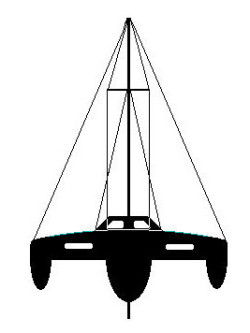

Trimaran, Horstman

40' x 24' x 6 Tons

24-Ft. Dia. Parachute Sea Anchor

Force 8-9 Conditions

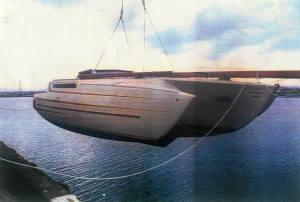

File S/T-20, obtained from Gary Habersetzer, Raymond, WA - Vessel name Amenity, hailing port San Diego, Tri-Star ketch designed by Ed Horstman, LOA 40' x Beam 24' x Draft 38" x 6 Tons - Sea anchor: 24-ft. Diameter military parachute on 400' x 5/8" nylon three strand tether and bridle arms of 60' each, with 1/2" galvanized swivel - No trip-line - Deployed in a gale in Mexican coastal waters about ten miles from Magdalena Bay with winds of 35-50 knots and seas of 8 ft. - Vessel's bow yawed 10° - Drift was minimal during 12 hours at sea anchor.

Gary Habersetzer is one of the original group of multihull builders/sailors who learned how to use parachute sea anchors directly from John Casanova (File S/T-1). The group included Carol Donovan, owner of the 35-ft. Horstman Tri-Star Lion's Paw, Jim Staggs, owner of the 41-ft. Nottingham trimaran Whither, Jack Beadle, owner of a 32-ft. Simpson Wild "Shifter" trimaran, and Bob and Marilyn Braggins, owners of the very first flush deck Horstman Tri-Star ever built, Puffin.

Gary bought his first surplus military parachute from John Casanova in 1975, using it in a whole gale aboard his first multihull, a 31-ft. Piver AA trimaran off Cape Mendocino, California. When Gary, along with Bob Braggins, was invited to fly over and help sail a newly-built Horstman Tri-Star from Seattle to San Diego, he brought along two parachutes.

The story about him boarding the plane with two 28-ft. C-9 parachutes rolled up under each arm - causing not too little anxiety among the passengers - is well known in multihull circles. Bringing those parachutes turned out to be a wise decision, however, because the Tri-Star ended up having to use one in a gale off the mouth of the Columbia River.

In the July/August 1979 issue of Multihulls Magazine Joan Casanova wrote about the dangerous behavior of the boat prior to deployment (reproduced by permission):

The small Tri-Star rose above the monstrous waves, sliding swiftly down each face. Every few waves which passed under the boat were just a little larger than the last ones. It sent the tri skidding off at a 45° angle, nearly coming to complete broaching position in the trough. the action gave the helmsman anxious moments before the boat would respond to the helm. All aboard knew the dangers of that position. They were aware that the tri exceeded a safe speed. Below decks all gear was rolling in the aisle. It was only a matter of time before the growing seas would roll the lightweight trimaran over. Bob Braggins, skipper of Puffin, reflects in his tone of voice those anxious hours, as if reliving them.

"I'm sure we would've gone over if we hadn't put out the chute. We had difficulty putting it over the side at first. The wind got hold and wanted to open it on deck. As soon as it took hold in the water, the boat began to ride easily and we began to relax. It was my first time using a chute, and believe me, I am sold!!"

Gary has used the parachute sea anchor too many times to list all of them. On the occasion of this particular file he and his wife Karen were sailing Amenity from San Diego to Cabo San Lucas when the wind and seas suddenly came up near Magdalena Bay. Amenity was hove-to for twelve hours, after which she resumed her cruise south. There is a photograph of Gary and Karen folding the parachute on Amenity's deck in the July/August '79 issue of Multihulls. The photo was taken by Joan Casanova.

In 1976 Gary Habersetzer went into business for himself as head of Marine Repair Service in San Diego. After two decades of multihull building experience he founded Pedigree Cats in Seattle in 1995. The company now builds large multihulls. At this writing there are several large Horstman Tri-Stars in the works, including one that is 105 feet long. A 52-ft. Shuttleworth design with a high-tech Aero-Rig is nearing completion. Pedigree Cats has also received an offer to build catamarans for an Austrian concern.

The short note that Gary sent in along with the filled out DDDB form reads thus:

I think you now know why we list the chute as standard equipment on all the cats we build. We have used them and know that you should not leave the dock without one.

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!