Trimaran, Piver

55' x 25' x 15 Tons

24-Ft. Dia. Sea Anchor

Force 11-12 Conditions

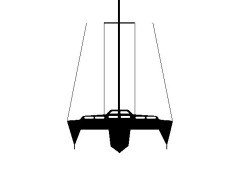

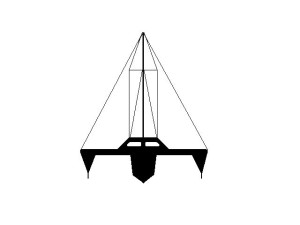

File S/T-19, obtained from Mel Pearlston, Petrolia, CA. - Vessel name Surrender, hailing port Petrolia, trimaran ketch, designed by Arthur Piver, LOA 55' x Beam 25' x Draft 4' 7" x 15 Tons - Sea anchor: 24-ft. Diameter Para-Tech on 600' x 3/4" nylon three strand tether and bridle arms of 75' each, with 5/8" stainless steel swivel - No trip-line - Deployed in a North Pacific storm in deep water about 500 miles west of Humboldt Bay (California) with winds of 70-80 knots and seas of 50 ft. - Vessel's bow yawed 10°.

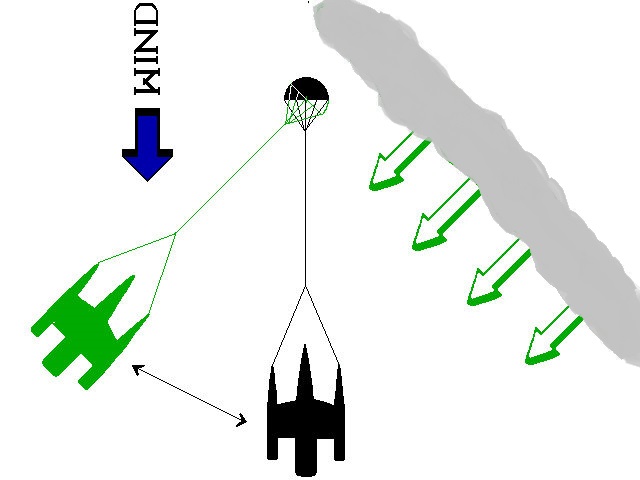

Mel Pearlston was sailing Surrender back to California from Hawaii in 1992 when she ran into a September storm. A 24-ft. diameter Para-Tech sea anchor was then deployed, which kept her three bows snubbed into the seas for about three hours. The anchored trimaran was then struck by a rogue wave coming in at an angle of 30-40°. As to what happened next, the best that Pearlston and Shane could determine after long telephone conversations is as follows. Either the trimaran was picked up and carried sideways, inducing considerable slack in the system, which allowed the yacht to lie a-hull temporarily. Or the sea anchor itself was picked up and thrown - possibly fouled - by the same rogue wave, causing the line to go slack and the yacht to lie a-hull. Or a combination of both (Fig. 40).

Although mercifully rare, large breaking rogues are capable of dealing swift and unexpected death blows to small craft. One needs to try to come up with additional tricks that might improve one's odds of survival in the event of such an encounter. Perhaps one such trick would be to deploy an auxiliary - smaller - sea anchor on a much shorter line off the approach ama, if one knew which side the rogue was going to come from. Or possibly the main hull, if one did not. This sort of strategy was once used on some of Richard Newick's earlier Vals, the idea being that if a capsize couldn't start it couldn't finish. Several OSTAR Vals, among them Three Cheers, rode out storms on double sea anchors. Perhaps this auxiliary sea anchor could be a weighted, 3-5 ft. diameter cone with a wire hoop sewn into the skirt to keep the mouth permanently open, deployed on 30-50 feet of line.

Conditions being life-threatening Pearlston made a quick decision to cut away the rig and run downwind. Transcript:

Surrender left Kauai, Hawaii in early September, 1992, when hurricane Iniki was just leaving the coast of Baja and turning west across the Pacific. There were three of us aboard Surrender, a modified Piver Enchantress, stretched to 55'. Surrender had been lovingly and heavily built over a twenty year period by a master craftsman, and I had been sailing her for five years in the Eastern Pacific. After sailing north on a port tack for a week, we turned right and headed across the top of the North Pacific High for our home port of Humboldt Bay. Just about this time hurricane Iniki was devastating Kauai, destroying every boat on the island. The distress channels were full of incoming calls, spread over a thousand mile radius. We were counting our blessings for having left when we did, thinking that we were home free.

I awoke three mornings later about five hundred miles west of Cape Mendocino to the blackest and most ominous horizon I had ever seen. The forecast was for a low pressure system to produce 40 knots of wind and seas of from 15 to 20 feet, but I didn't believe a word of it. The wind built quickly from the NNE to 45 knots, at which point I made the decision to deploy our 24' Para-Tech sea anchor. The anchor was attached to 600' of new 3/4" three strand, 75' bridle arms, a 5/8" SS swivel, and was secured to the boat by massive, custom-made stainless steel bails on the bow of each ama. No trip line was used, but two 24" diameter mooring balls were used for floats, together with a man overboard pole to make visual observations and recovery easier.

By the time the sea anchor was deployed and the boat buttoned up (which included lashing the helm amidships), the wind had built to fifty knots and the seas were building quickly. Over the next three hours we rode extremely comfortably to the sea anchor while conditions continued to deteriorate. The wind increased to a sustained 70 knots, gusting over 80. The larger waves were in the fifty foot range, and the swells were 600 feet apart. While riding to the sea anchor Surrender did not yaw perceptibly. As we rose to each wave the boat would rise and begin to be carried back until the anchor rode came up tight. Then, like a huge rubber band, it would gently pull us through the top of the swell. It was truly a testament to the use of the sea anchor. To this day I remember thinking how eerie it was that we could be so comfortable in such conditions.

At the height of the storm I felt the boat rising to a particularly large swell. At some point I realized that this wave had come from a point some 30 to 40 degrees off our starboard bow. At the top of the wave, after the anchor rode had stretched out and we were being pulled through the crest, something happened and the tension on the rode was suddenly released. Surrender free fell backwards down the face of the wave, and upon landing was completely submerged. Sometime during this fall one of the forward salon windows was broken. After assuring myself that the boat was still upright, I took stock of our situation. The main cabin had three feet of water in it. All of the items stowed on the starboard side of the boat were now on the port side. Upon going topside, I found that our decks had been swept clean of all stowed gear, including items that had been secured with heavy webbed strapping. I nailed a piece of plywood, with a closed cell foam gasket secured to one side, over the broken window. Next I went forward and cut loose the sea anchor bridles because the boat was broadside to the swell and there was no appreciable tension on the rode, and I assumed that the sea anchor was gone. I did this so that the rode would not foul our prop or rudder as my intention was to run down swell and deploy drogues. In retrospect, this was a poor decision. I did not consider the possibility that the anchor was tumbled and/or fouled. All I could think of was not spending one more moment than necessary with Surrender broadside to those huge seas.

While I unlashed the helm, I made my next mistake. I attempted to start the engine for maneuverability without checking the engine room. Apparently the starter had gotten wet and it immediately shorted out causing billowing clouds of smoke to emerge from the engine room. At the same time I realized that the helm was not responding and when I inspected the rudder post my worst fears were confirmed. The two inch bronze post had snapped below the steering quadrant. It appeared to have twisted like a piece of plastic almost 90 degrees before breaking. There was less than half an inch of mangled post left to work with - far less than that needed for my emergency tiller to attach to. The next eighteen hours passed in a blur. We bailed the boat out with buckets, as the books and food on the cabin sole of the salon turned the water into a thick gruel that foreclosed the use of either our electric or hand pumps. The wind had subsided to fifty knots, and the seas to the 30 foot range by this time, and a small amount of headsail allowed Surrender to ride hove-to quite comfortably. By the end of this period I was able to jury rig a steering quadrant to the rudder post utilizing a modified clamp-on quadrant from an Alpha auto pilot, and we got back underway. The next five days were spent limping into Humboldt Bay fighting the cold (we had no dry cloths or blankets) and our dwindling supply of amps.

Better decisions would have left us with an answer as to whether some part of the sea anchor system had failed, or if the sea anchor had merely been tumbled and/or fouled, and if so, whether it might have eventually recovered and restored its pull. In any event, I have never traveled offshore since without two complete sea anchor rigs aboard, and would never hesitate to recommend their use for rest, repairs, or as a defensive storm tactic. I consider it the single most important tool we carry.

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!