D/M 23

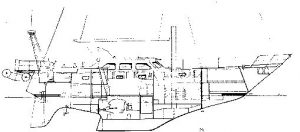

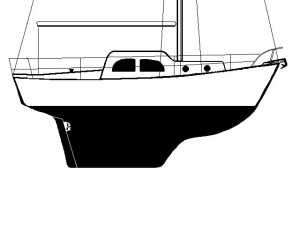

Monohull, Bruce Roberts Voyage 388 cutter

39' (12m) x 23 Tonnes, Fin keel

39' (12m) x 23 Tonnes, Fin keel

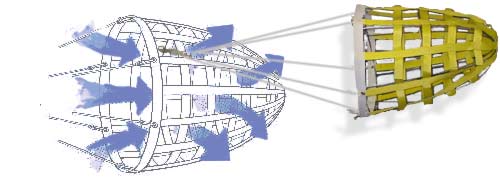

Jordan Series Drogue

Force 9+ Conditions

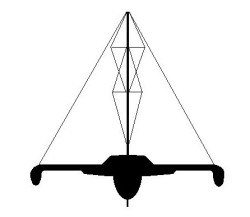

File D/M-23, obtained from Rob Skelly, Canada - Vessel name Pauline Claire, hailing port Vancouver, monohull steel hulled cutter designed by Bruce Roberts and built by Rob Skelly himself, LOA 39' (12m) x LWL 34' x Beam 13' (4m) x Draft 6' 10" (2.1m) x 23 tonnes - Fin keel - Drogue: Jordan Series Drogue 100' leader followed by 130 cones on 7/8" (22mm) nylon double braid rode plus 6.8kg lead weight with 24' (7m) bridles of 7/8" 3-strand nylon - Deployed in deep water 120 miles south of Madegascar while singlehanded midway on passage from Reunion to Durban in winds of 50+ knots and breaking seas of 16 - 23 ft. (5 -7m) - Speed was reduced to about 2.5 knots during 36 hours of deployment. Total drift was about 70 nm.

Having built his boat himself, Pauline Claire ended up being considerably heavier than the design specifications. Rob then set off from British Columbia, Canada, on a circumnavigation with no previous sailing experience. All was well until the Indian Ocean when he was notified by his shore-based sister of the oncoming gale that he could not avoid at his cruising speed.

Rob's Jordan Series Drogue was permanently set up with the bridles in place attached by spliced eyes to the cleats welded to the aft quarters. Below the cleats on each side were vents that opened below into the engine room. These vents were quickly ripped off by the bridles once the drogue was deployed. After that there was nothing to chafe the bridles and, fortunately, there were no waves that pooped the stern that might have flooded the engine room through the now missing vents.

The drogue itself was stored in a locker on the deck above the transom from where it could be quickly thrown aft into the water.

Knowing the storm was coming, Rob was running downind under bare poles and auto pilot. The wind vane was pinned to lock the hydrovane runner amidships. The wind at this point was maybe 45 kts but the waves had not yet built to maximum.

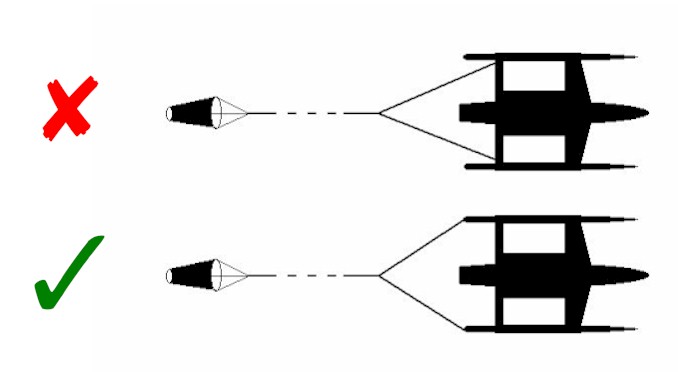

The drogue was then deployed by throwing out the weight. The drogue rushed out, but two of the cones did snag (and tear) on the swim platform on the way out.

Once the drogue was out everything settled down. Autopilot was turned off, and Rob retired below from where he could watch the drogue through his Lexan companionway hatch. He was then able to sleep and send emails to his sisters by Iridium to reassure them that life was getting to be 'a bit of a drogue'.

The drogue would cycle between full load and slack as the waves passed by underneath. When under full load the bridle would be fully stretched out, once the load reduced the bridle would then retract and twist over itself. This did not seem to affect the performance of the drogue but might, over time, have caused some chafing issues though none was noted.

After two nights the wind had dropped and progressively eased to 15 kts while the seas continue to be large. Because the boat speed had dropped, there were times when the drogue was quite slack and, because of the movement of the boat in the waves actually got wrapped around the hydrovane rudder. Once the load came on again the rudder was taking all the strain. Rob attempted to unwrap it but was unable to do some. Eventually, fortunately, during a slack period on a wave it did unhook itself.

The drogue was rigged with a strong recovery line attached to the V of the bridle. This long line was brought back to a which with which Rob was able to then haul in the drogue while the bridles remained attached to the cleats.

Once the bridle V was onboard, the bridle arms were disconnected from the cleats and the rest of the drogue was winched on board in sync with the slack from the waves, hand-tailing as the cones would not go through the self-tailer. Totaly recover time was maybe two hours.

Lessons Learned

- The number of cones used were correct for the design weight of the boat. However, the boat ended up being much heavier than intended and so the number of cones was insufficient. This resulted in a speed of 2.5kts instead of 1.5kts when on the drogue. Since he was headed in the right direction anyway this was not of any concern. Rob has since had another 25 cones added.

- Rob also changed the 3-strand bridles into double braid (25mm) to prevent the twisting.

- He has also added another 8 lbs (3.6kg) of lead to the end of the drogue, separated from the other one by about 6' (2m). These are shackled to an eye splice at the end of the rode.

- The vents have been replaced with flat deck plates so there is nothing to snag.

- Rob has not yet figured out how to solve the problem of the cleats on the swim deck snagging the cones on deployment.

- There is a small wooden platform on the hydrovane on which one can step while pinning the vane in place. This had a sharp corner which also snagged a cone on deployment. That has now been rounded off.

- Rob recommends retrieving the drogue as soon as possible when conditions improve. so as to prevent the risk of it wrapping around a rudder.

Having discovered that the retieval was not as hard as expected, especially with the retrieval line going to the V of the bridle, Rob has no hesitation in using the drogue.