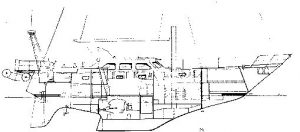

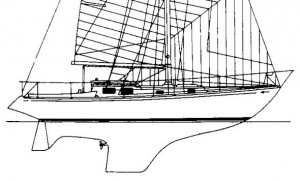

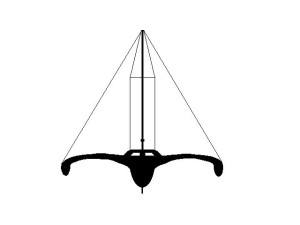

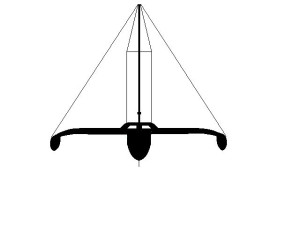

Catamaran, custom design

46' x 25' with 8' daggerboards x 9 tonnes

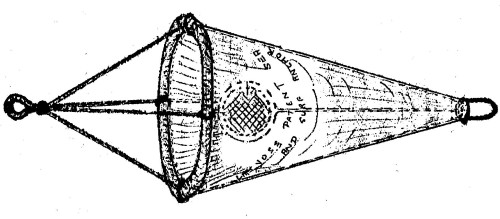

Jorrdan Series Drogue

Force 9 Severe Gale

File D/C-10 obtained from Mike Reed of Santa Barbara, California. Vessel name Rum Doxy, hailing port Santa Barbara. fast crusing Catamaran, custom designed by Copelli and Mike Reed himself. LOA 46' x Beam 25' x Draft 8' with dagerboards down. Drogue: home made 300' Jordan Series Drogue (150 cones) on double braided nylon with 30lb length of chain at the end, and 50' x 3/4 3-strand bridle arms deployed in deep ocean on passage from Japan to Alaska during a fast-moving remnant of a Tropical Storm. Winds of 45kt gusting to 50+ and breaking waves of 7m. Drifted 30 miles over 12 hours.

Attachment points: custom stainless steel chainplates 1/4" x 2.5" x 18" with 6, 3/8" bolts each set on aft cross beam about 16ft apart. 5/8" galvanised shackles on galvanised thimbles. Zero chafe.

Mike Reed has over 40,000 miles under his belt, so it is no surprise that he was well prepared, having both a para-anchor and a series drogue ready-rigged in case he needed them. In this case, deployment of the drogue was a simple matter of dropping the weighted end over the stern and allowing the drogue to rush out (keeping feet and hands clear). Once set, it allowed him to rest overnight with no drama, and then resume his way in the morning when the gale had passed.

We deployed our JSD in force 9 conditions off the coast of Japan. We were eastbound 5 days out of Yokohama when we were overtaken by the remnants of TS Leepi, which had become a fast-moving extra-tropical cyclone. The wind was in the high 40's, gusting into the mid 50's with seas of approximately 7 meters. The boat was under autopilot, our speed was 9-11 knots under bare poles and, although an occasional breaker would push the stern around a bit, the boat was handling the conditions comfortably, taking the seas in a dignified manner off the starboard quarter.

However, as the wind continued to build, the boat began to plane on the gusts, reaching speeds of 15 knots. The autopilot continued to handle it well but the sun had set, the wind was building and it was time to slow the boat.

We had pre-rigged both the JSD and parachute anchor prior to leaving Japan. I chose to deploy the JSD rather than the parachute anchor as we were traveling in the same direction as the weather with 4,000 miles of sea room and I expected the gale to pass by us quickly.

Deploying the drogue off the stern was simply a matter of dropping the chain weight at the end overboard. The drogue ran out smoothly and behaved brilliantly, slowing the boat to 3.5 – 4.5 knots as the stern lifted gently over the seas. We have a hard dinghy in davits and I was concerned that the breaking waves would swamp it, but the sterns would lift as the waves passed and the dinghy never got wet.

We turned off the autopilot and settled in. The gale continued for another 3 hours then began to abate. By sunrise the wind had dropped to 15 knots with seas approximately 2 meters and we retrieved the drogue and carried on.

A few points are worth commenting on.

First, the forces exerted on the boat by the drogue were truly impressive. The pull from the JSD, while gradual, would cause us to stagger if we were not holding on.

Second, one often hears that a disadvantage of the JSD is that they are difficult to retrieve, but in this particular case we found it fairly easy. Before deployment I had rigged a long pendant to one of the bridle arms. When it came time to retrieve the drogue we simply led this line forward to the bow roller, released the bridle arms and motored slowly forward, pulling the drogue in by hand. The whole operation took about 15 minutes.

Third, and most surprising, was that when we retrieved the drogue in the morning we found that most of the cones had frayed badly, particularly those closest to the boat that, presumably, were subjected to the most stress and turbulence,. The leading edges were most affected, but the trailing edges were frayed as well. This was after only 2-3 hours of gale force conditions. The cones were 2.2 oz ripstop nylon from a kit supplied by a marine canvas supplier. They no longer sell these. We made new cones out of 4 oz polyester with a hem on the leading edge. I n retrospect I wish that I had used even heavier cloth with hems on both edges.

Fourth, I was a bit surprised at our speed while lying to the drogue. After reading many accounts of monohulls lying to a JSD I expected our speed to be around 2-3 knots. We averaged 4 knots, which may have contributed to the rapid degradation of the cones. When we replaced the old cones with the new ones we found that the supplier had sent us 10 fewer cones than required for our size boat, which may have accounted for the higher speeds.

Many people comment that the JSD is hard to retrieve. However Mike, with forethought, rigged up an extra length of line to the bridle so that he could take that around to the front, and then haul it in as he motored forwards towards the drogue. This obviously requires turning the boat 180 deg and then having someone at the helm to make sure they don't drive over the drogue while it is being retrieved, But 15 minutes has to be a record for JSD retrieval!

The alternative method is to winch it in over the stern, timing the winching with the slack produced as each wave passes (see Tim Good's report D/M-21).

The fraying of the cones after just a few hours of gale is certainly of concern. Steven Brown also noted the same problem and wondered if a longer length of rode before the first cone might help. Plus, of course, using good strong cloth. In this case Mike tells us the closest cones were also lifting out of the water, so maybe indeed this is a cause of cones fraying.