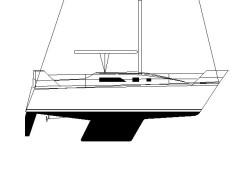

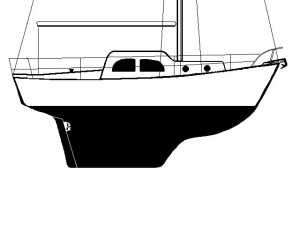

Hunter 31 Sloop

31' x 5 Tons, Fin Keel

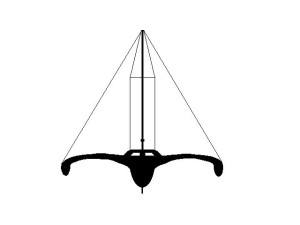

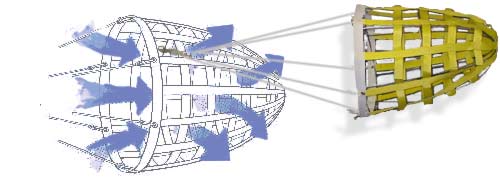

15-Ft. Dia. Sea Anchor

Force 8 Conditions

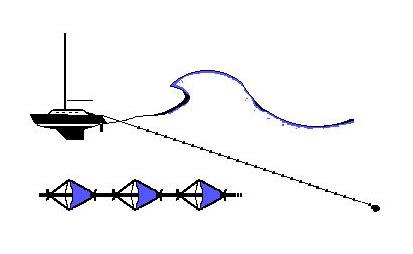

File S/M-32, obtained from Chris Brann, Sausalito, CA. - Vessel name Snow Dragon, hailing port Juneau, Hunter sloop, designed by Cortland Steck, LOA 31' x LWL 28' x Beam 11' x Draft 5' 10" x 5 Tons - Fin keel - Sea anchor: 15-ft. Diameter Para-Tech on 150' x 5/8" nylon double braid with 1/2" stainless steel swivel - Partial trip line - Deployed in a low system in deep water about 150 miles west of Noumea, with winds of 45 knots and seas of 15-20 feet - Vessel's bow yawed 30° - Drift was 8 n.m. (confirmed by GPS) during 5 hours at sea anchor.

Chris Brann was a participant in Compuserve's mammoth drag device and storm tactics debate. The debate has since been "packaged" and placed in the library of the SAILING FORUM. When in Compuserve click on the traffic icon, type GO SAILING and look for a file called Thread on Drogues, Sea Anchors and Storms in the "Seamanship and Safety" library.

Brann cruised Alaskan waters with Snow Dragon, a fin-keeled Hunter 31, before sailing her all the way to Brisbane, Australia. Aside from two incidents of rudder failure, the boat held up fairly well. The failures were caused by the rudder manufacturer's use of smaller shaft dimensions, a defect since corrected by Hunter Marine (owners of older Hunters should make certain that their boats are not affected). The second incident of rudder failure occurred on the Noumea leg of the journey, where Brann had to deploy a sea anchor for damage control and attitude stabilization purposes. Transcript:

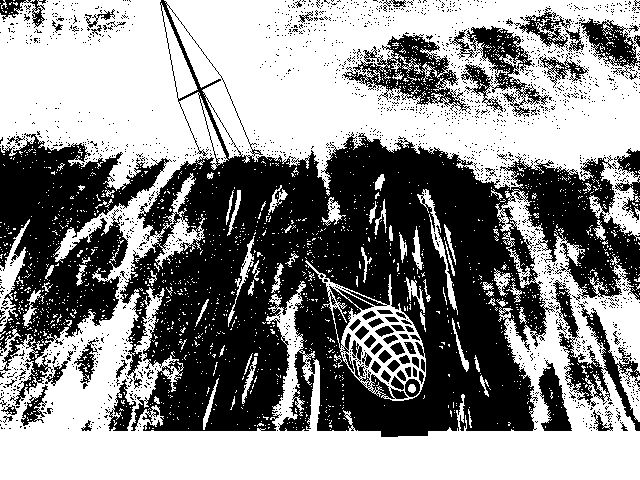

0300 November 26, front passed, wind backed to southwest, over 30 knots. 0410 We suddenly lost steering. After mounting the emergency tiller, checking cables and movement of the rudder post we realized we'd lost our rudder again. The seas were over 12 feet and continuing to build. The wind was 40-50 knots. With no rudder we fell into the trough, lying parallel to the waves. 0510 We deployed a 15 foot diameter parachute sea anchor from the bow... to prevent capsizing, and to try and stabilize the vessel while we built an emergency rudder. This held the bow into the waves. By now the wave crests were breaking regularly. The anchor was attached to the bow, via 300 feet of 5/8 inch double braid nylon. This made things a bit more comfortable, and it was easier to drill holes and so forth. Unfortunately, the outer covering [of the double braid] chafed, so I pulled enough rode in to put sound line on the cleats. This resulted in about 150 feet between the sea anchor and the bow. This was not enough line to absorb the energy....

At about 1000 a large wave broke over most of the vessel, filling the cockpit, even though it came from forward. The bow cleats are welded to a 1/4" stainless plate that is in turn bolted through the sides of the vessel. The strain [of the breaking wave] curled this plate through more than 90 degrees, crushed the pipe forming the legs of the cleats, and then broke the 5/8" line (breaking strength 14,400 lbs.) I determined that the line had broken rather than chafed through by observing that the ends of the strands were all about the same length and were slightly fused. The strain also curled the main plate holding the forestay. Loss of this plate would have meant loss of the mast. The structure of the boat was also damaged, opening the joint between the hull and deck on the port side, and we started to take water in through the gap.

1040 I rigged a trysail to try and stabilize the boat a bit, though it didn't really head it into the seas, and we were pretty much parallel to the waves for the rest of the day. We had crests break on the hull several times each hour, fortunately none of them were big enough to capsize us. I hung over the stern and dismounted the paddle from the wind vane (self-steering device) for use in building an emergency rudder, which occupied us for the rest of the day.

About 1600 the wind and seas had moderated, and we hoisted a storm staysail, streaming a 36" Galerider drogue from the stern. This got us moving towards Australia, though our course was still determined by the direction of the wave troughs. At 1900 wind was SSE 20-25 knots.... The next day we rigged the emergency rudder. It broke after a few hours, but we redesigned it and put it back on. We spent the next week improving the rudder and sailing to Australia.... Directional control was eventually established by a combination of jury rudder and a light drag towed behind the boat.... We tied to the customs wharf in Brisbane at 0720 local time on December 4.

Comments: This was a normal low pressure system, with wind and seas that would present no danger to a well-found boat equipped with a rudder. Two other vessels were nearby and in radio contact with us. One was 32' long, and the other 43'. Neither of them suffered any damage from the weather, and in fact both were able to rendezvous with us to provide additional lumber for use in making another emergency rudder in case our first one failed. Our problems were solely a result of the rudder failure.

What we'd do next time: Shackle all 300 feet of nylon line to the [steel] anchor and let out the [steel] anchor and 100-150 feet of chain. This approach was used by some friends on a 42 ft. Lord Nelson with success in the Tasman sea. In our case, while it lasted the sea anchor stabilized the boat quite a bit, especially compared to our gyrations without a rudder.