Monohull, Norseman 447

45' x 14 Tons, Low Aspect Fin Keel

Sea Squid Drogue

Force 12+ Conditions

File D/M-12, obtained from Paula & Dana Dinius, Long Beach, CA. - Vessel name Destiny, hailing port Long Beach, monohull, Norseman 447 designed by Robert Perry, LOA 45' x LWL 37.6' x Beam 13' x Draft 6.5' x 14 Tons - Low aspect fin keel - Drogue: Australian Sea Squid on 200' x 1/2" nylon braid rode + 12' of 3/8" chain, with bridle arms of 20' each - Deployed in the Queen's Birthday Storm in deep water near 25° 55.7' S, 175° 28.4' E (about 400 miles SSW of Fiji) with winds of 80-100 knots and seas of 60 ft. and greater - Vessel's stern yawed 45° and more with the owner steering - Speed averaged about 6 knots during 15 hours of deployment - Destiny was damaged after somersaulting off a huge stacking wave and had to be abandoned.

In June 1994 a regatta of pleasure yachts left New Zealand, headed for Tonga. En route they were devastated by an unseasonable cyclone.

The event coincided with the celebration of Queen Elizabeth's birthday, and has been referred to as the Queen's Birthday Storm ever since. About half a dozen boats were abandoned. Two dozen sailors had to be rescued. The yacht Quartermaster sank with loss of three lives.

Destiny, the subject of this file, did a spectacular dive off the top of an eighty foot wave. Dana Dinius told Victor Shane that it was like going over the falls on a surfboard - the yacht fell straight down. He distinctly remembers being weightless while hanging on to the wheel. Destiny went end over end when she finally hit bottom, doing a cartwheel and snap roll that bent her mast all the way around the hull. Dana's leg was badly broken at the hip, incapacitating him. Paula somehow managed to drag him inside, where the two spent a night to remember, rescue aircraft circling overhead.

The life and death rescue drama that transpired the next day is described in great detail in other texts and videos, among them Tony Farrington's book Rescue In The Pacific (International Marine Publications), and Ninox Films's epic video, Pacific Rescue (Ninox Films, Ltd., PO Box 9839, Wellington, NZ).

At this point we would like to digress and say something else about the Queen's Birthday Storm: the cyclonic conditions were exacerbated by microburst-generated ESWs. The term ESW - extreme storm wave - was coined by Jerome W. Nickerson when he was head of NOAA's National Weather Service Marine Observation Program. "The ESW appears to be about 2.5 times the significant wave," wrote Nickerson in the NOAA publication, Mariner's Weather Log (Vol 29, No. 1 - see also Vol 37, No. 4, the Great Wave issue). ESWs arrive as colossal walls of water with a deep trench in front. When aligned with the seaway they may be technically classified as episodic (wave events that stand apart from all others during the analysis interval). When misaligned, they may be classified as freaks, mavericks or rogues, because they intrude into the dominant seaway at angles of up to 50°, causing "stacking" and "wave doubling" where they intersect with the regular significant waves. Sometimes ESWs come in pairs, the largest following on the heels of the first. On rare occasions they may even come in sets of three, a fearsome phenomenon dubbed the three sisters by ancient mariners.

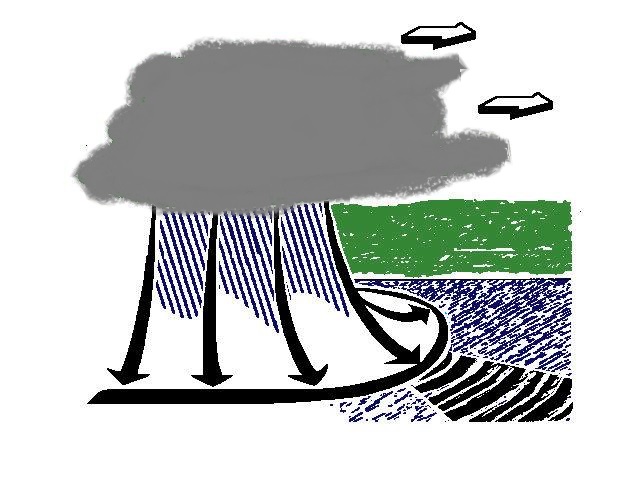

GUST FRONT OR SHEAR LINE

Cold, dense air from the upper part of thunderstorm cell plummets downward. When it reaches the surface it spreads out on all sides, but most strongly in the direction of the movement of the storm. The outer edge is called a gust front or shear line. Bold arcs in lower right corner indicate dangerous area in which the gust front is sufficiently synchronized with the prevailing waves to reinforce/amplify a few significant ones into Extreme Storm Waves (ESWs). There were dozens of massive thunderstorm cells embedded within the Queen's Birthday Storm.

Putting all things together, several components can be applied to the Queen's Birthday Storm, setting the stage for the genesis of ESWs: Inordinately steep pressure gradients, resulting from the confrontation of differing air masses; a rapidly developing, warm-core cyclonic system, rotating clockwise in the southern hemisphere; wind field rapidly increasing to above Force 10 (50 knots sustained), producing significant waves of about 20 feet. The picture so far is fairly representative of the average storm. However, we now have to look for an additional reinforcing agent or catalyst by means of which significant waves can be built up to the 80-ft. monster that threw Destiny end over end in the Queen's Birthday Storm.

According to Jerome W. Nickerson, one such catalyst or reinforcing agent can be found in extreme downbursts. Such downbursts are associated with the rapid venting of energy bottled up in discrete thunderstorm cells embedded within the larger storm system. Thunderheads have been known to reach heights of 65,000 feet. The cold, dense downdraft from such a concentrated energy cell will sometimes produce wind gusts of 100-knots and higher - as with tornadoes. When such a downburst reaches the surface of the sea it could statistically synchronize with, organize, reinforce and amplify the existing significant waves into ESWs.

We already have a 979 mb cyclone in the Queen's Birthday Storm. Add sudden, catalytic release of energy bottled up in massive thunderstorm cells, pulsing down against the surface of the sea and thereafter spreading out on all sides (but most strongly in the direction in which the storm is moving) in the form of a gust front or squall line.

Speculation locates the genesis of an ESW at a place where the speed and direction of the moving gust front coincides with the speed and direction of the highest existing waves (lower right corner, bold arcs in Fig. 55). The developing ESW - the dominant wave in the train - will now collect more energy from the wind than the other waves. Moving faster, it will also merge with and collect energy from the smaller waves it is overtaking, in effect "stacking" and "snowballing" into the stature of a genuine extreme storm wave.

Was this the case in the Queen's Birthday Storm? Well, it could have been a contributing factor because we have many first hand accounts of violent thunderstorm activity. In fact there was so much electrical activity that many claimed to have seen strange lights - some even thought they had seen flying saucers. Commander Larry Robbins of the HMNZS Monowai (one of the rescue ships) reported seeing such lights, as did other personnel aboard the ship. "Suddenly the decks lit up... the sky just lit up and we could see for miles," said Lieutenant Andrew Saunderson. Jim Helden, captain of the cargo ship Tui Cakau III - whose Fijian crew took Paula and Dana off Destiny - saw the electric show, as did Paula and Dana Dinius themselves. Said Paula in the interview that she and Dana did for Ninox Films, "The lightning was approaching... I believe we went right through the center because of this lightning show... it was just amazing... you could just see it coming directly, and then it was on us, and it was just all over us... you could feel it as it cracked... it would just go through your body."

One can also infer microbursts from the baffling testimony of Dana Dinius himself. Dana was bewildered by the chaotic nature and direction of the wind as he struggled with Destiny's helm: "We had 85 knots of wind, and it really wasn't a wind... it was a mist, it was really intriguing... there was a real presence there, an evil that we felt... the wind would come in from the right or the left and swirl up in front of us in a big mist, and then it would exit... and it might exit forward, it might exit over my shoulder... it wasn't a consistent type of a wind, and with the lightning cracking all around us, it was... we can only describe it as a real evil." (Courtesy Ninox Films).

Only a severe microburst - or macroburst - could have exhibited such chaotic characteristics (meteorologists call downbursts with outflow diameters of no greater than 2.2 nm microbursts, and those with outflow diameters greater than 2.2 nm macrobursts). Depending on her position beneath the downburst, Destiny might have been blasted with 80-100 knot gusts from any number of directions. Transcript:

On June 4, 1994, five days out of Auckland, New Zealand, approximately 400 nm SSW of Fiji, my wife Paula and I were hit by an out of season 979mb cyclone. It was to come without warning and deliver constant 80-85 knot winds (gusts over 100 knots) and 15 meter breaking seas. At the storm's conclusion 21 people were rescued, 7 cruising boats abandoned and, sadly, three lives lost. Our boat and home for seven years, a Norseman 447 named Destiny, was a 45 foot fiberglass performance cruiser designed by Robert Perry. Unfortunately, she was not to survive the storm, pitch-poling off a 100 foot stacking wave resulting in severe damage to both the boat and her crew.

The cyclone dropped on us without warning. Our land-based weather service had forecasted for us 35-40 knots of wind during the evening, coming from a 1005mb LOW located to the north around Fiji. Since our weather fax printouts from both New Zealand and Australia confirmed that report, we had no reason to suspect anything else. At 1800 hours, after our evening check-in and with 3 meter breaking seas behind us, we elected to go to bare poles and deploy our drogue. At the time we felt it to be a bit of an overkill, but thought it would provide us with a relatively quiet night. Our drogue was an Australian SEA SQUID, an orange plastic cone designed to channel water into its sides and out the rear, creating a braking effect. Not expecting any real weather, we deployed it off the port side on 200 feet of 1/2 inch yacht braid, and 12 feet of 3/8" chain to hold it down under the surface. The line was run through the aft port chock and up to the primary winch in the cockpit. A bridle of sorts was jury rigged by tying a shorter piece of 1/2 inch line to the rode and running it back to the primary winch on the starboard side. By adjusting the length of the both leads we could get the drogue to trail directly behind the boat, or to either side.

During the night the seas increased to giant mountains towering well above the mast. It had the look of traveling through snow-capped mountains during a lightning storm. The P-3 Orion crew that held station over us during the rescue, said their ground search radar was giving them 80 to 100 foot variances, indicating trough to peak heights. We found our drogue set-up to be optimal in conditions that far exceeded what we expected that night. Destiny was held to 3-4 knots in the troughs and 7-8 knots running down the giant wave faces. There seemed to be little or no yawing, and steering control, while being a little sluggish from the trailing drogue, was responsive enough to handle the storm. The ride in general, although very wet, was relatively smooth.

Although the speed was well under control we still felt it necessary to hand steer the boat. The blast of wind hitting the transom as we raised up out of the trough (generally 35 knots in the trough and 80+ on the crest) was strong enough to drive the stern of the boat hard to port or starboard. Reaction had to be quick and complete enough to bring the stern back around before the breaking seas engulfed it. Failure to complete this maneuver left us exposed at an angle to the breaking seas, which would in turn push the boat further around, greatly increasing the danger of a broach/roll. There were times we were hit so hard that Destiny, even with the helm hard over, barely corrected stern to the seas before the next wave crest. It is our feeling that the autopilot (an Auto Helm 6000-Mark II) would not, at the peak of the storm, have been able to correct fast enough to complete the maneuver.

We feel our chances of surviving the storm were greatly increased by choosing an active role at the helm. This decision took into account exhaustion and exposure. Warm, tropical weather diminishes exposure problems, and as for exhaustion, we've learned in extreme conditions the pure adrenaline pump will keep you going many more hours than you think is humanly possible now. Had we been in a colder climate we may have decided differently. We also realize that an active technique is not for everyone. For those who do not wish an active part, a much larger drogue that would hold the boat at a snail pace, "perhaps" would give the resistance needed to stay stern-to with the aid of an autopilot. We are sure, however, the boat would take a terrible beating given the size and power of the seas we experienced. As it was, we lost most of our cockpit canvas and saw extensive damage to the supporting stainless steel long before the pitch-pole.

What was learned:

1) 200' of rode is not enough. Twice during the night our drogue broke loose and pulled out of the wave behind us. Destiny shot from 7 knots to 14 knots in the bat of an eyelid. Had there been any way to extend the rode at that point we would have, but by then the weather was critical. The cockpit was constantly awash. Hanging on and steering was all we could manage. We learned that given a shorthanded crew, the rig you go into extreme weather with is most likely what you will be forced to stay with for the duration. Hindsight tells us that even if we didn't think we would use it, we should have rigged more line. Our suggestion is to have the stern anchor rode rigged so you can attach the drogue at a moment's notice.

2) We found that directly downwind was the most stable and survivable course. In our case, at 7 knots, burying the bow was not a concern. Our biggest concern was being caught sideways and rolled. We attempted to cheat to the SSW whenever possible to work out of the dangerous SE quadrant of the storm, but found it almost impossible to make much ground without putting the boat at risk of a broach.

3) The most critical point of the storm, with respect to survival, came when the winds had subsided a little, during the eye of the storm. The wind was never the real problem. As it fell from the 80's to the 50's the seas, which up to this time had their crests blown flat, began to break more top to bottom. The wave faces became steep enough to force corrections port or starboard to keep from broaching in the troughs, even traveling at 7 knots. Three times during the morning hours, Destiny's keel broke loose and we slid down the wave face like dropping in an elevator. It was at this point we felt control had been lost and we issued our PAN PAN call. As the wind began to clock south and increase again, there developed a secondary wave direction which created a "stacking effect." Ultimately, we feel that's what killed Destiny. Two or three breaking waves stacking on top of one another produced a bottomless situation. Under those conditions we don't think any drogue could have held the boat from that fall. There comes a time in extreme conditions when your survival boils down to the luck of the draw. We feel this was one of those times.

4) We have been asked if our chances would have been better with a sea anchor. Not having tried one we will never know. We do know that after the boat pitch-poled and had been dismasted, we were lying a-hull for many hours. During that period we suffered countless 120° knock-downs, but were never rolled again. Perhaps the broken mast, which was wrapped around the boat, gave it additional stability? Who knows. The boat did take the pounding and seemed to hold up pretty well. But it should be noted here that conditions were such that things could have gone pretty much any way at that point. Had the boat broken up, a hatch tear off or a window break (we had the storm shutters on), we would not be here today. To attempt to man a life raft in those conditions would have been a sentence of death.

Being inside, without control, was the first time we felt helpless to protect ourselves. Because the boat withstood the pounding [while lying a-hull] one could make a case for the para-anchor. However, given the size of the seas we were in, we would worry about how the anchor is attached to the hull. The issue of chafe goes without saying, but even more worrisome is the question of attachment points. What stresses are at work when you are hit by a breaking wave taller than a telephone pole moving along like a freight train? And this continues for 12 to 16 hours? We question the ability of many cruising boats to hold up under those conditions. Still, all things being equal, with adequate warning of extreme conditions, we feel we would chose to go with a large para-anchor, 500 feet of heavy line, attached with a wire bridle distributing the load to points throughout the hull. In our opinion, there is a good case for both a drogue and a para-anchor aboard a seaworthy cruising yacht. In the final analysis it's up to each of us to decide on the solution we can live with. When that moment comes, it's nice to have options at hand.

In subsequent telephone conversations Victor Shane pressed Dana Dinius about the perennial question as to whether one should run directly downwind or try quartering the seas. After thinking about it Dana replied that on Destiny, in that storm, it had to be directly downwind. However he added that in other situations he might decide to quarter the seas, especially if the bow was beginning to bury itself in the base of the next wave now and then.

On another matter, Dana confirmed that he and Paula felt most vulnerable when the wind dropped in the eye of the storm. He said, "as the wind dropped, the waves became hollow." This is something that Shane had heard before, something that one should be prepared for. Compare with John Glennie's statement in File S/T-7: "Without the wind regulating the seas, I was afraid that two or three waves might ring hands and turn into rogues."