D/M-15

Monohull, Contest 40

40' x 8 Tons, Fin Keel

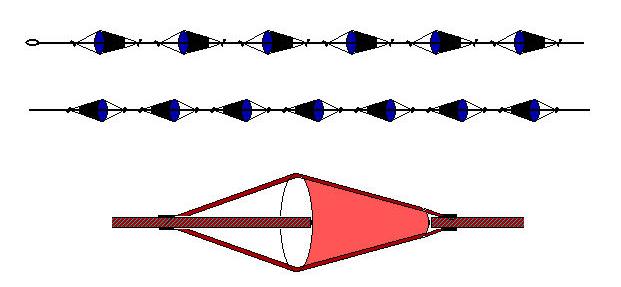

Series Drogue - 120 x 5" Dia. Cones

Force 9-10 Conditions

File D/M-15, obtained from Robert J. Burns, Townsville, Australia - Vessel name Peter Sanne, hailing port Detroit, MI, monohull, Contest 40, center cockpit ketch designed by Conyplex, LOA 39' 9" x LWL 29' x Beam 12'6" x Draft 6' x 8 Tons - Fin keel - Drogue: Jordan series, 120 x 5" diameter cones on 300' x 3/4" nylon double braid rode, with bridle arms of 15' each and 35 lb. anchor at the end of the array - Deployed in a whole gale in the Gulf Stream with winds of 45-55 knots and seas of 20 ft. - Vessel's stern yawed 20° - Drift was about 12-15 nm during 6 hours of deployment, with a 3-4 knot current running.

Robert Burns made up his series drogue with the help of Professor Noël Dilly (previous file). En route to Newport from Bermuda he ran into a whole gale in the Gulf Stream and deployed it. Six hours later he lost the series drogue due to chafe. He then deployed a 2-ft. diameter conical parachute type drogue. This is an important file which provides an immediate comparison between the two different drogue concepts. The following are excerpts from Burns's article entitled Streaming A Drogue, appearing in the December 1993 edition of Yachting Monthly (reproduced by permission):

I've run before rising gales, but never with such menacing seas. There were three distinct inter-active wave patterns that combined to form massive pyramids which collapsed periodically in an immense surge of white water. As long as I could avoid the breaking portion of the waves there was little danger of sustaining damage from the mass of breaking seas colliding with the yacht.... We were truly surfing now, down wave faces that would break behind us, catching us as we increased speed, then engulfing the yacht in white water. Steering required intense concentration to keep the stern pointing in the direction of the breaking sea and present the minimum surface area, reducing risk of broaching. I was conscious of the forces of the rudder. The last thing we needed was to lose steerage.... If the storm was going to build for another four hours, it was time to try another tactic before it got too dark to see what we were doing.... The series drogue consisted of a 300ft length of 3/4" double braid nylon that had 120 5-inch diameter cones spliced onto the line through their axes. The drogue had an anchor attached to the outboard end for a weight and was attached to the stern with a bridle. The gusts were furious now. The seas were 25-30 feet with faces at 45 degrees and 50 degrees and breaking frequently. The shrieking of the wind in the rigging and the whip-like crackling of the ensign was making me most anxious. It was time to stop. We were above hull speed most of the time now, and it was hard to control the vessel. I sent Curley astern to kick the anchor over the side that would commence the deployment of the drogue.

The drogue had been rigged at the stern with anchor attached. As soon as the weight was released the drogue line paid itself out of its storage box. The tow line streaked out with dramatic speed and force. After less than a minute the drogue was deployed and the cones began to exert their resistive force on the bridle. The slowing effect was phenomenal. Deploying the drogue was like bungee jumping off a 30ft wave with a 40ft. yacht. The feeling of being elastically attached to the sea itself is hard to imagine. After a minute or so we had slowed from 8 knots to 1.5 knots. The stern was pointed aggressively into the wind and sea. It was as if we had entered a calm harbor of refuge. The yacht held her position near the top of the waves' crests. When a wave approached and threatened to break on board, the drogue would pull us up and over the top of the breaking waves. There was no possibility of a breaking wave hitting us broadside, as we were always above the majority of the white water.

We furled the remaining portion of the jib, tied off the helm, checked to make sure everything on deck was secured, and then went below. Inside the main cabin the noise of the gale was much less. With the reduction in the yacht's motion, our situation seemed not too bad. We were all exhausted and took the opportunity to try to get some sleep. The time was 2130. I got up several times to check the situation. Despite the roar of breaking seas as we were pulled over the tops of breaking waves, I slept surprisingly well....

At about 0230 the sound of waves falling on deck seemed to increase and the motion of the yacht changed. Gone was the elastic "bungee effect." I was about to climb out of my bunk and put on harness to inspect the rig, when the boat heeled sharply to port under the force of a wave striking the starboard quarter. The sound of flowing water was everywhere. In the next instant the companionway doors shattered, and an angry stream of water rushed into the saloon.... I reached for the nearest overhead light... it came on to reveal the main saloon with 2-3ft of seawater sloshing above the cabin sole. Debris of the splintered hatch floated with charts, books, wet blankets and sleeping bags. The cockpit was full to the top of the coamings with frothing sea water. The night was dark, but I could still make out the towering peaks of white water around and above us. I glanced at the wind instruments; we were lying with the wind just aft of the beam, we had no headway. "So," I thought, "this is what it is like to lie a-hull." The priorities were to clear the boat of water, and try to repair the shattered companionway in case we were boarded by another sea. And to check what had happened to the drogue. The crew were in favor of launching the life raft. I recalled previous conversations about abandoning a damaged yacht. In the 1979 Fastnet Race it had been a major contributor to loss of life. We were still very much afloat. The thought of taking to a life raft was not at all appealing to me.... My priority was to reset the drogue.

I found the bridle dangling over the transom, severed on both sides. The 3/4" nylon bridle had been abraded by the self-steering mounting brackets. There was damage to the stern pulpit and deck fittings, evidence of the forces and motion exerted on the hull by the drogue before it parted the bridle. It was imperative to get the stern facing the seas again. I pulled several lengths of anchor rode and mooring lines out of the aft lazarette, tied them together, and streamed them over the transom. This had little effect as the line was mostly polypropylene and skipped along the surface. Every moment we continued to lie a-hull we were at risk of being struck by another breaking monster. I recalled that I also had a small hand-made parachute-type sea anchor stowed below. My wife had constructed it some years ago for our coastal cruising around Tasmania and it had never been used.

The parachute sea anchor was a 2ft diameter cone made of synthetic canvas with ¼" polypropylene lines braided together to form the shrouds. It looked frail in comparison to what it had to stand up against. I tied the parachute to the longest length of line and let it slip over the side. Nothing happened at first. When all 300ft of line was out and the chute was subject to some forward motion the line came taut. There was no bridle now, so the tow line was only attached to the starboard stern cleat. The yacht yawed to port, aligning the stern almost into the wind and sea. Our forward velocity was about 2 knots. Big waves would cause us to surge forward and down the waves faces, as the chute didn't have sufficient surface area to slow us down against the push of big seas. We were much better off now. If the chute held we would be safe.

Gone was the feeling of "bungee jumping" [associated with the series drogue]. The forces exerted by the chute were sharper [jerkier] and nowhere near as powerful. However, the strategy of lying stern-to was still the most comfortable and safe. The little chute did well. We had no serious broadside wave strikes, even though there were still a lot of breaking seas around us. The chute was not able to pull us up and over the breaking waves, so the occasional wave dumped on the stern. As the yacht had a center cockpit, there was less danger of it being filled.... Dawn came slowly. The fury was fading from the wind and it seemed like the little chute would see us through the gale.... We cranked out a tiny bit of jib from the furling gear. The yacht pointed directly downwind, similar to riding with the series drogue. I wondered why I had not thought of using a bit of jib earlier.... By noon 6 June we had crossed the Gulf Stream axis into the cold water of the US continental shelf.

Robert Burns constructed another series drogue for his next boat, the 50-ft. aluminum Holman & Pye ketch, Eclipse, which he and his wife Kathryn sailed to Australia.

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!