Monohull, Morgan 382

38' x 9 Tons, Low Aspect Fin Keel

Five 14" Plastic Cones In Series

Force 11 Conditions

File D/M-8, obtained from Jim Gilster, St. Clair Shores, MI. - Vessel name Windsprint, hailing port St. Clair Shores, monohull, Morgan 382 designed by Ted Brewer & Jack Corey, LOA 38' 4" x LWL 30' 6" x Beam 12' x Draft 5' x 9 Tons - Low aspect fin keel - Drogue: 5 each 14" diameter plastic cones (Davis Instruments) on 300' x 5/8" nylon three strand rode plus 20' of chain - Deployed in a storm in deep water about 200 miles north of Bermuda with winds of 60-70 knots and seas of 20 ft. - Microbursts - Vessel's stern yawed 10° - Speed was reduced to about 2 knots during 33 hours of deployment.

On 3 June 1984 the British sailing barque Marques capsized and sank with loss of 19 lives, 80 miles northeast of Bermuda while participating in the Tall Ships Race. On 14 May 1985 the replica sailing vessel Pride Of Baltimore capsized and sank 240 miles north of Puerto Rico. On 31 August 1986 the Calida, a 135' replica of the Cutty Sark, capsized and sank in similar circumstances 90 miles southeast of Cape Fear, North Carolina.

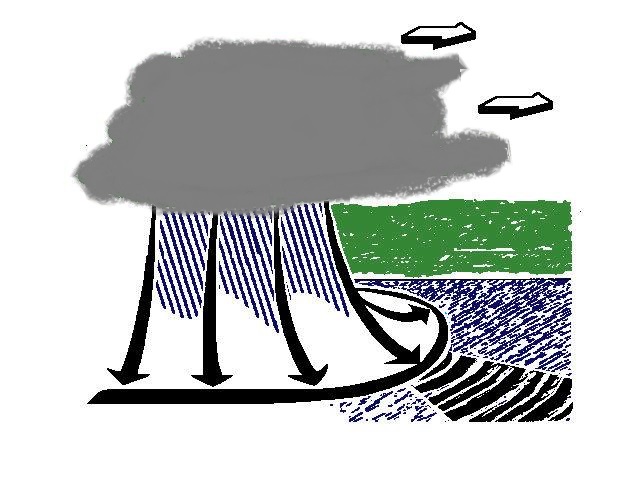

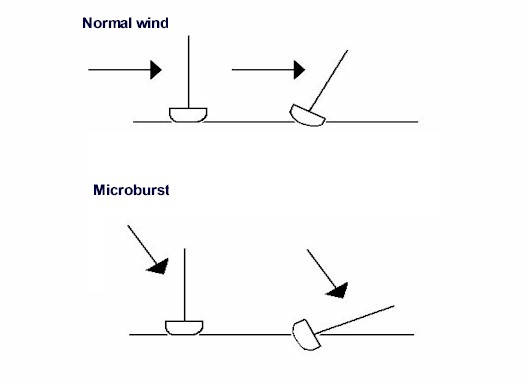

The culprit in each case: Microburst. Microbursts, or "white squalls," as they are sometimes called, are associated with massive thunderstorm cells embedded within existing storm systems. A microburst involves a sudden, cataclysmic release of bottled-up energy in the form of one or more downbursts. These downbursts - sometimes sporting wind gusts of 100 knots - consist of cold, dense air which plummets down to the surface of the sea, thereafter spreading out on all sides, the outer edge being called a gust front or shear line.

This precipitous downward movement of air, also known as wind shear, is now believed to have been the cause of a number of previously inexplicable air tragedies, among them the tragic crash of Delta flight 191 in Dallas in 1986. The crash of Delta 191 prompted the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to sponsor the development of NEXRAD - "next generation" pulse-doppler radar capable of detecting wind shear as well as incipient tornadoes and twisters. (Today NEXRAD is in wide use throughout the world). The added leverage gained by the wind, because of its downward vector, has no doubt been the undoing of many a sailing vessel. Try sailing under the wash of a hovering helicopter with a sailing dinghy and see what happens. The downward blast from those rotors will instantly knock your dinghy down. The same phenomenon occurs in nature, only on a much, much grander scale - microbursts. It is Victor Shane's opinion that the Queen's Birthday Storm of June 1994 was reinforced and exacerbated by a great many microbursts (see File D/M-12).

Sailing vessels situated directly beneath the microburst will find themselves in grave peril, especially those with lofty rigs. The added leverage gained by the wind will easily knock down, capsize, or drive the bow down under, as was the case with the Marques. The downward force of the wind struck against her lofty rig from the port quarter, burying the bow; the sails, then on the starboard side, served as the lever to spin the Marques around and quickly roll her onto her beam ends. She filled with water and sank in a matter of minutes.

It is interesting to note that the builders of the old Baltimore Clippers seemed to have had foreknowledge of microbursts, and made allowance for this vice of nature in the way that they designed the rigging. In an article called The Baltimore Clipper, appearing in volume 14 of Sea History, Melbourne Smith writes, "Everything aloft was made as light as possible to reduce windage and save weight. The gear could be struck at will by the large number of men carried aboard. Some of it was purposely fashioned light as a built-in safety factor so that it could be `removed by the Lord' if the crew failed to do so in time." (Courtesy Sea History, a publication of the National Maritime Historical Society.)

Getting back to file D/M-8, Windsprint, a Morgan 382, was being sailed to England in June 1984 when she was caught in the same storm system that sank the Marques. The owner of the boat, Jim Gilster, was quick to take down all sails and set a new course downwind, a few degrees off the rhumb line to Bermuda. Windsprint was soon averaging 7 knots on bare poles with the helm manned. The skipper then deployed a drogue consisting of five 14-inch diameter plastic cones, shaped like Mexican hats, manufactured by Davis Instruments. (Davis is still manufacturing the "Mexican hats", but for use as "rocker stoppers" only). The five cones, spaced 18" apart at the end of a 300' nylon rode, did a good job of keeping the stern of the yacht pointed into the seas for some 33 hours. In fact, once the helm was properly adjusted and locked no further steering was required. The crew was able to retire down below and rest in relative comfort, seventy knot winds and twenty foot seas raging outside. Transcript:

We were in the storm pattern that sank the Marques on June 3, and we were told of its sinking by one of the tall ships continuing on to Halifax. When we arrived in St. George's Harbor in Bermuda we witnessed services being held aboard the one tall ship that dropped out of the race to assist in the search and rescue effort.

The five plastic cones were spaced 18" apart; I rigged them up with 5/16" braided nylon, doubled, with a thimble at the bend, and figure eight knots at the holes in the cones. I attached all this to 20' of chain and 300' of 5/8" nylon line, led to the port stern cleat and port sheet winch. I felt confident it would all hold up. It did, in 70 knot winds and 20' seas. We slowed down to 1.5 to 2 knots from 7 knots on bare poles. I adjusted the wheel to allow us to quarter the waves, and we were "comfortable".... We were occasionally pooped, but with a bridge deck and tight hatch, little water entered the cabin. Although each of the five cones was cracked when we hauled them back in, we did not notice any diminished resistance while "at anchor." I am in the process of affixing two cones together to make five sets of two each, somehow each set of two cones sealed/glued together for strength.

Interestingly, these cones were originally marketed as "sea anchors" in the early 60's when I purchased a set for this purpose. I think Davis should beef them up a bit and again denote them "sea anchors." I would, and will, use them again in the same manner. I was very pleased with the way they slowed the boat down, although, of course, I had no lee shore to contend with.

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!