Trimaran, "Rose-Noëlle"

41' x 26' x 6.5 Tons

24-Ft. Dia. Parachute Sea Anchor

Force 8-10 Conditions

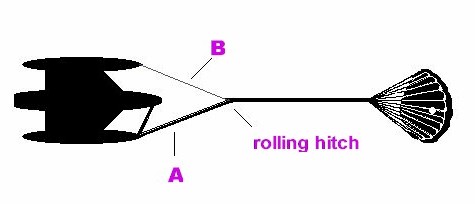

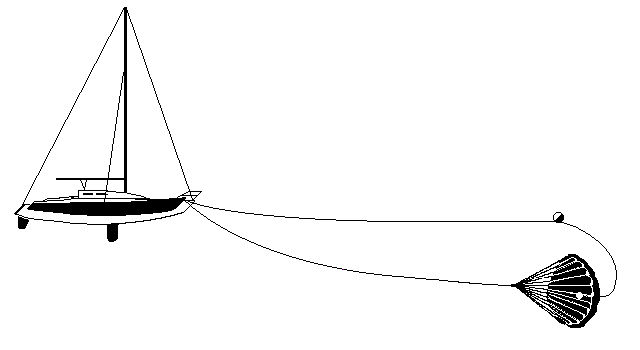

File S/T-7, obtained from John Glennie, New Zealand - Vessel name Rose-Noëlle, hailing port Nelson, New Zealand, trimaran designed and built by John Glennie, LOA 41' x Beam 26' x Draft 3' x 6.5 Tons - Sea anchor: 24-ft. Diameter military chest reserve parachute on 300' x 3/4" nylon three strand tether and bridle arms of 40' each, with 1/2" galvanized swivel - Full trip line - Deployed in a gale in deep water about 150 miles southeast of the East Cape of New Zealand with winds of 40-60 knots and seas of 20 ft. - Vessel's bow yawed 10° - Fouled trip line collapsed the parachute after 10 hours, allowing the trimaran to lie a-hull and be capsized by a rogue wave - Crew survived 118 days adrift inside the inverted hull.

On 4 June 1989 the trimaran Rose-Noëlle capsized some 140 miles east of the Wairapa coast of New Zealand. The crew of four spent 118 days adrift inside the upturned hull. The incident subsequently became a source of some controversy, leading to an investigation by the New Zealand Ministry of Transport. John Glennie's exclusive story was first published in the November 1989 issue of New Zealand Yachting. Later, John wrote a book about the ordeal called Spirit of Rose-Noëlle.

John Glennie is an institution in the land of Down Under. New Zealand and Australian magazines have referred to him as Free Spirit of the Pacific. John and his brother David started out by building a 35' Piver Lodestar trimaran in their Father's Marlborough farm shed in America. They named it Highlight and sailed away. After spending eight years roaming all over the Pacific, John and David wound up in Australia, where they worked on and delivered many famous boats, including Mike Kane's Spirit Of America, a Kraken 55 trimaran of Lock Crowther design.

Glennie's own boat, Rose-Noëlle, took nineteen years of intermittent work to build and launch. John sailed it to the Great Barrier Reef, then across the Tasman Sea to New Zealand, where he gained boat-building work at Paremata, working with the brother of New Zealand's America's Cup helmsman, David Barnes. Every cent that he earned went into equipping Rose-Noëlle for self-sufficiency on high seas. Innovative rigging, water still, solar panels, radios, radar, etc., and a 24-ft. diameter parachute sea anchor.

Rose-Noëlle set sail from Picton New Zealand on June 1st (winter Down Under), headed for warm waters and Tonga. The crew consisted of John Glennie, Philip Hoffman, Rich Hellriegel and Jim Napelka. On the third day out they ran into a southerly gale and for a while used a Sea Squid (bullet-shaped Australian plastic drogue) to slow the boat down. Later they stopped the boat and deployed the parachute sea anchor. It pulled the three bows of Rose-Noëlle into 20-ft. seas and kept them there for the next ten hours.

The full trip line, probably left hanging loose in the sea, must have fouled with the parachute because sometime after those ten hours the trimaran began to yaw increasingly from side to side, until finally she was lying a-hull. It was night and little could be done. An hour or so later, the crew heard the approach of a great roaring noise, much like that of a huge - Hawaiian - surf wave. The rogue wave hit the boat broadsides and rolled her over very quickly. In the article that appeared in New Zealand Yachting Glennie stated that just before the capsize the wind had eased and he was concerned that without the wind "regulating" the seas, two or three waves might "ring hands and turn into rogues."

After the capsize it took the crew a while to settle down to the business of survival. Wrote Glennie, "I had to keep their hopes up and get them over the shock of the first stage. If people give up, they die." Eventually they all adapted, surviving the next 118 days adrift inside the inverted hull of the trimaran. There was plenty of food left inside, and the problem of fresh water was solved when John devised a system for collecting and storing rain water. From then on it was patience and perseverance, despite numerous gales, saltwater sores, and the occasional brawl that one might expect in such dire and cramped circumstances.

The inverted trimaran drifted "all over the place." It is estimated that she covered, ignominiously, a journey of nearly 2,000 miles, during which the cramped crew experienced somewhere between 17-20 gales - an average of one every week! And astonishingly enough, four months after the Royal New Zealand Air Force planes had given up the search for Rose-Noëlle she washed back up unto Great Barrier Island, at the edge of the Hauraki Gulf, the well-populated sailing area of New Zealand. Transcript of hand-written notes that accompanied John Glennie's feedback:

The para-anchor worked well and I was most impressed till it fouled.... The trip line fouled the chute and with the chute partially collapsed we lay a-hull.... The wave was so big that it would have rolled the Cutty Sark! They [rogue waves] are out there. I think three waves got together, so it was probably 60 feet high. I saw a similar 60-ft. vertical wall of water in 1968, mid-winter, 43° south, below Tahiti. Water was running down its face and I remember the noise it made as it came towards us.... Next time I won't use a trip line. I could have got the chute back in with the electric capstan in the calm after the storm.

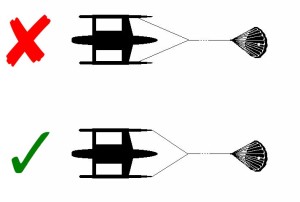

A reminder that the Casanovas used full trip lines for eighteen years with seldom a foul-up. According to John Casanova, the trick is to have a small swivel at the float, and keep the trip line fairly taut - no excess slack hanging loose in the sea to foul with the parachute or rode. Bear in mind, also, that if the wind force increases the main rode will elongate, requiring that the full trip line be slackened off accordingly (otherwise it may trip the canopy). By checking the trip line tension on a regular basis, one can tell if it is too loose, or too tight. One should also use the binoculars to keep an eye on the big red float itself. If it is behaving awkwardly - as though it had hooked onto a big fish - it may mean the trip line is too tight and needs to be slackened off a little.

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!