Trimaran, Kismet

31' x 18' x 2.5 Tons

20-Ft. Dia. Parachute Sea Anchor

Force 10+ Conditions

File S/T-2, condensed from the writings of Randy Thomas - Vessel name Celerity II, hailing port Victoria BC, "Kismet" trimaran designed by Bill Kristofferson, LOA 31' x LWL 29' x Beam 18' 6" x Draft 30" x 2.5 Tons - Sea anchor: 20-ft. Diameter cargo parachute on 300' x 7/16" nylon three strand tether and bridle arms of 100' each, with 1/2" galvanized swivel - No trip line - Deployed in hurricane Freida in deep water in the South Pacific, with winds of 50-60 knots and seas of 30 ft. - Vessel's bow yawed 20°.

This file was condensed from articles by Randy Thomas and additional information provided by others, among them Bob Wilson of the British Columbia Multihull Association, to whom the author is indebted.

Celerity II, a Kristofferson-designed, light displacement Kismet 31 was en route to Kosrae from Rabaul (Solomon Islands) when she had an encounter with hurricane Freida in February 1982. As the wind and seas continued to build, Randy Thomas found options narrowing. Running off was out of the question. It would take Celerity II into a screen of low-lying atolls, and toward the eye of the storm. And Randy had once tried lying a-hull in a blow off Point Conception, California. It had been a bad experience.

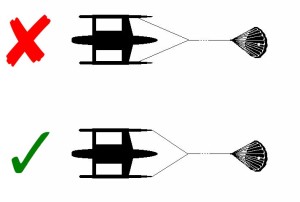

With her reefed main set as a riding sail and the tiller lashed amidships, Celerity II lay quietly hove-to for a while. But the wind was building in 5-knot increments and soon it became clear to Randy that the mains'l would have to come off altogether - taken off the boom. It was time to set the parachute sea anchor. Randy had never set the chute before. With safety harnesses snapped on, he and his companion Thea carried the 20-ft. diameter parachute on deck. Crests broke over the boat as Randy crawled onto the narrow floats to shackle each end of the bridle to the heavy duty U-bolts which he had installed three feet inboard. "`Next time rig the bow bridle before you leave port,' ran my mental memo." (Writing in the article that appeared in SAIL Magazine). They dunked the chute and watched, as the boat's drift payed out the 400' of tether and bridle. But Celerity II continued to lie-ahull!

Overcome with dismay, Randy wanted to get the knife and cut the whole rig away, but Thea shouted above the noise of the wind that he should try leading the bridles off the extreme outboard tips of the floats before doing so. Randy was skeptical at first, but then decided to give it a try. He would have to unclip the two snatchblocks from the U-bolts (three feet inboard), wriggle out to the ends of the narrow floats and re-attach them to pad-eyes forward. It was a formidable struggle, but it did the trick. Celerity II immediately rounded up and began facing the seas. In his article appearing in the June 1982 issue of SAIL, Randy describes Celerity II's behavior (reproduced by permission of SAIL Magazine):

She bobbed easily over the upwelling crests, first backing swiftly, then popping upward like a suddenly released balloon. I was certain we would be buried under each seemingly perpendicular wall. No water came on deck. The bridle led perfectly, never coming into contact with either the hulls or the deck. There was no jerking at the blocks - only a gradual tension and relaxation as the nylon "springs" dissipated the heavy loads. We were anchored in mid-Pacific. We might have been anchored in a monsoon-torn harbor, except for the longer periods between each extraordinary rise and fall.

With the situation in hand they went down below and prepared a meal. Radio reception faded in and out, but they were able to piece the fragments together: tropical storm Freida had been upgraded to a hurricane, and her eye was 150 miles to the north! Just before dark Randy estimated the wind speed at about 50 knots sustained, with seas of 30 feet from trough to crest. Many of the waves were observed to be breaking heavily along their full lengths, but Celerity II had settled down into predictable cycles and seemed to be doing OK.

The night was a lonely vigil for the two. Randy writes that lying in the dark cabin they were mentally overwhelmed by the noise of the combers, rising in pitch as they approached the boat and then falling in pitch as they receded - like approaching and receding freight cars. The wind was shrieking through the rigging and the radar reflector up on the mast, creating an incessant racket that tore at their nerves. It was impossible to sleep. At dawn they were able to prepare a breakfast, and the radio informed them that the eye of the storm - packing 100 knot winds - had re-curved and was passing to the north for the second time! Thea put her head into the plastic observation bubble in the coach roof and surveyed the white seas around them. Suddenly she exclaimed she could see the parachute in the distance. As the boat climbed the next wave, Randy saw it too, "a shimmering disc, suspended like a huge jellyfish in the face of the bottle-green sea. The shroud lines reached out like tentacles, holding us safely in their grasp. We knew we were safe as long as our chute held." Well, the chute did hold, and, other than some minor damage to the trim-tab on her self-steering rudder, Celerity II emerged from her encounter with the lady Freida intact. In the same article Randy Thomas sums up his opinions:

Cruising safety depends on having options. And the parachute sea anchor can offer you a crucial alternative when the chips are down. Lying a-hull in heavy seas can result in damage, capsize, or worse aboard a light-displacement boat that is easily "tripped" by a fin keel or a submersible float. A parachute will hold such craft safely head-to-the-seas, minimizing drift and the danger of breaking crests.