S/P-3

S/P-3

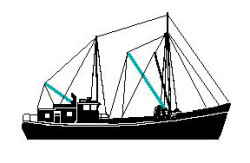

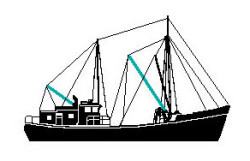

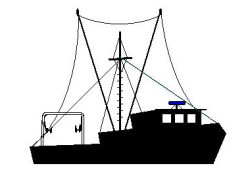

Commercial F/V

66' x 120 Tons

32-Ft. Dia. Sea Anchor

Force 9-10 Conditions

File S/P-3, obtained from Captain Michael Monteforte, Kenyon, RI. - Vessel name First Light, hailing port Point Judith, RI, commercial F/V, designed by Walter Bechman, LOA 66' x LWL 62' x Beam 21' x Draft 12' x 120 Tons - Sea anchor: 32-ft. Diameter Para-Tech on 150' x 1¼" nylon three strand rode, with 3/4" stainless steel swivel - Full trip line - Deployed in a whole gale in shallow water (60 fathoms) about 150 files from Boston with winds of 55 knots and seas of 20 ft. - Vessel's bow yawed 10°.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, commercial fishing ranks as one of the most hazardous occupations in the United States.

Those of us who sail offshore for pleasure can pick our season and our route, and change both if necessary. But the skipper of a commercial F/V is up against an economic imperative. "Breaking up a trip" can be an expensive proposition. He has spent hundreds of dollars in fuel, ice and provisions, and the crew has to get paid whether they catch fish or not. So what happens when the Weather Service issues an untimely bulletin? Given today's shaky economic picture, the skipper has to make a difficult decision as to whether to go ahead with the trip, or to abort and head back for port with the holds empty.

In the course of interviewing scores of offshore fishermen, Victor Shane discovered that, as a general rule, most will stay on the fishing grounds and ride out the average gale, especially if the trip is still young. The majority will steam back for port in the event that the forecast is upgraded from "gale" (34-40 knots sustained) to "storm" (48-55 knots sustained). Sometimes they get caught out there in between.

Now when a commercial F/V runs into an offshore gale it is standard procedure to "jog into it" - an expression used by commercial fishermen themselves. The engine is placed in slow forward and the F/V makes just enough way to enable the helmsman to keep the bow pointed as high into the teeth of the gale as possible. Fuel is spent in jogging into the seas; the hull may pound some; there is the wear and tear on everything and everyone. And if the vessel loses power, if she springs a bad leak, or if something major - like a pump - breaks down, she may end up needing the assistance of the Coast Guard.

This is why commercial fishermen were among the first to use parachutes at sea. With the parachute set they can shut down all engines and stay on top of the fishing grounds, anchored to the surface of the ocean in relative comfort. Transcript of Captain Monteforte's testimonial:

I used sea anchors for four years on my last boat, the Dyrsten. She was 60' long by 20' wide, made of yellow pine planks with oak ribs. Her gross weight was 38 tons. We used surplus parachutes then, but suffered with the problem of the chutes blowing out, so we always carried a spare. I thought about a chute for my new boat, First Light, but because she is at least three times heavier than Dyrsten, I didn't follow up on the idea, until last January, when I called Para-Tech, after seeing their ad in National Fisherman. I purchased a 32' diameter chute... a well-made, extremely rugged looking sea anchor.

We started using it on the very next trip. We would fish all day, and lay to the chute during the night. What we experienced at sea anchor was a very peaceful motion, as the bow of the boat tracked its way into the oncoming swells. The ride was different than if you were to jog into it. I suppose there was just less pitch, allowing for a good night's sleep. On one particular trip in March '88 we were fishing at least 150 miles offshore when, on the second or third day of the trip, the barometer started to fall rapidly. Now, ordinarily, we are left with two choices if the weather deteriorates: steam home, or lay to. Unless the forecast is really bad, we invariably lay to. At any rate, we set the chute before dark and when I got up at dawn the wind had already shifted to the northeast and was blowing 30 knots. Having noticed that the barometer was still low, I decided to remain at sea anchor a while longer. As it turned out we remained at sea anchor for another day and night. The wind increased to fifty five, sixty knots, with higher gusts.

The whole time that we were hove to the sea anchor we were comfortable and relaxed. When it was over, we were rested, in good shape, and anxious to get back to work. In my opinion, a sea anchor, used with good judgment, is an invaluable tool.

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!