S/M-36

S/M-36

Arpège 29 Sloop

29' x 3.6 Tons, Low Aspect Fin/Skeg

12-Ft. Dia. Sea Anchor

Force 8-9 Conditions

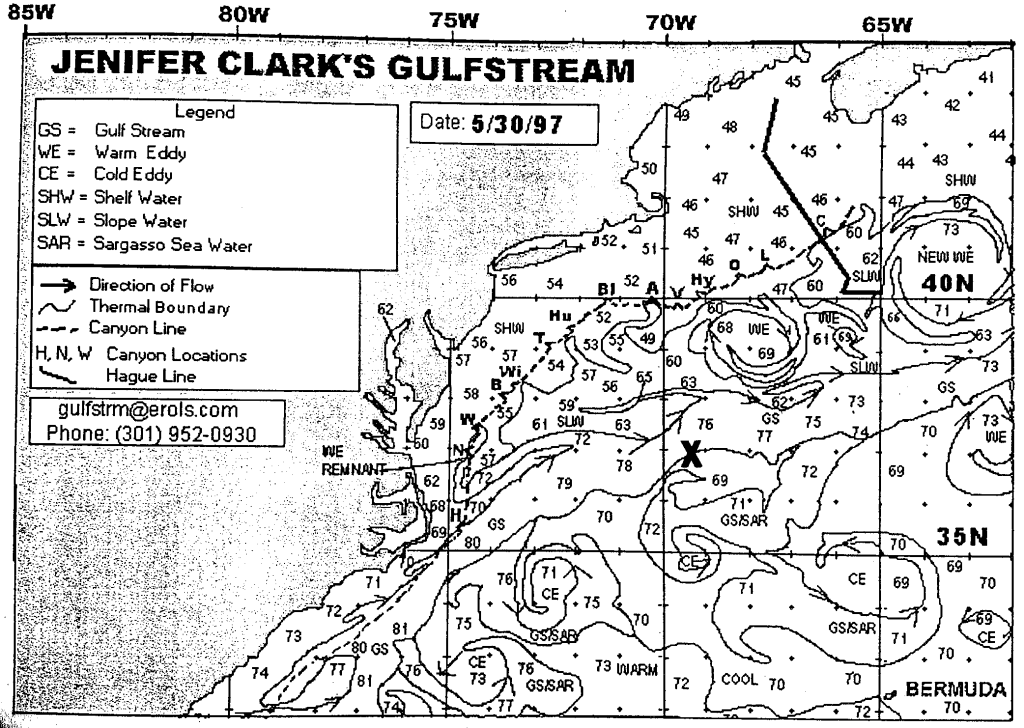

File S/M-36, obtained from Eleanor Tims, West Hagbourne, England - Vessel name Moon River, hailing port Southampton - Arpège sloop, designed by Dufour, LOA 29' x LWL 22' x Beam 10' x Draft 5' x 3.6 Tons - Low aspect fin keel & skeg rudder - Sea anchor: 12-ft. Diameter Para-Tech on 300' x 5/8" nylon braid rode with 1/2" stainless steel swivel - Partial trip line - Deployed in a gale in deep water about 50 miles north of Casablanca, with winds of 35-45 knots and confused seas - Vessel lay broadsides to the seas due to fouled sea anchor - Drift was about 80 n.m. in 32 hours.

Eleanor Tims has been a die-hard sailor for twenty years and has her own sailing school in the UK, offering practical boat handling and confidence-building courses. She has cruised her Dufour Arpège 30 out of Hythe Marina in England, sailing nearly 5,000 miles a year, now and then shaking a white-knuckled fist at Fastnet Rock on a passage to the fair harbors of Ireland, or waving a hasty goodbye to Ushant Island on a wind-driven - compulsive - jaunt to Santander harbor on the northern coast of Spain.

Eleanor is addicted to sailing. She has written many articles describing some of her hair-raising experiences at sea, the most infamous of which took place in the Bay of Biscay in 1994 - Force 9 and 25-foot seas, the mast about to come down, crew seasick, the diesel and the VHF dead, a roller furling genoa in ribbons and turned into screaming banshee, rocky islands and shoals looming close in the night, etc. etc.

Somehow the indefatigable, indomitable Eleanor Tims manages to emerge from such ordeals with a wave, a nod, a wink and a wicked sense of humor. Where would we all be without our sense of humor at sea?

In November 1996 Eleanor and friend Tom were sailing Moon River to the Canaries from the Moroccan harbor of Mohammedia when they ran into a gale and tried to deploy a sea anchor. What follows is a hard-won lesson that the lady would like to pass on to others:

We left Portugal for the Canaries with a favorable NE wind and decided to divert to Casablanca, Morocco, in order to break the long 600 mile leg into two stages and also to visit an "exotic" country. After leaving the harbor of Mohammedia our tack lay to the SW, but the wind, which had been from the NE for a long period, did a complete volte-face and came from the SW. I decided, nevertheless, to leave, as the forecast was for Force 5/6 and I thought that I could lay in a long tack to the NW and then to the South and perhaps the front would pass over in that time. However, things did not work out according to plan, as firstly there were very big seas running and secondly the wind increased past Force 6, to 7 and then 8. We were already becoming very tired and it was obvious that the time had come - indeed was past, as it was now dark - to put out the para-anchor.

Because it was dark, I took a long time in carefully preparing everything to ensure that is would run smoothly when launched, perhaps an hour. When I went up onto the foredeck, it was found that the deck-light was not functioning, so I had only the fitful light of a flashlight shone from the cockpit towards me. First of all I launched the pickup buoy and line, followed by the float buoy, but these were torn from my hands by the wind (nearly 40 knots) and by waves sweeping over the deck and over me. I then realized that the genoa furling line made things complicated and that I ought to have launched all this gear beneath the furling line instead of above it, so I pulled it in and tried to stuff it back into the sea under the line instead of over. Trying to do this caused a tremendous snarl-up, so I was forced into spending a long time lying sprawled on the deck in the almost continuous dark, with waves washing over me, trying to sort it all out. Eventually I decided I had it just about right and once more launched it all, following it finally with the para-anchor and 100 metres of rode. This done we turned in. However, things didn't seem right somehow. The bow was clearly not pointing into the waves, as every wave swept us over sideways, sometimes very nearly beam on, is how it felt. We were quite clearly lying ahull, and an inspection of the wind instrument confirmed that wind and waves were beam on. We passed an entirely wretched night, and were so tired the following day, with the wind steady at about 40 knots, that we were too tired to do anything much about remedying the situation. I did realize that the para-anchor hadn't opened, and as I could see both buoys close together, I also realized that the whole lot had snarled up together. We attached the rode to the [steel] anchor and let out a few metres of chain, so that it now ran out of the boat through the bow roller instead of through a deck fair-lead. This didn't improve things at all, in fact it probably worsened them, as I suffered some damage to the bow roller as a result. We had another perfectly horrible day, drifting backwards for the Strait of Gibraltar, far beyond our original starting point [more than 60 miles].

Day 3 saw me in more positive mood. "We have to get this thing in," I told Tom, so he did the muscle work. The wind was still 30+ knots and it took us about 50 minutes to bring the bundle in, and then the sad story could be seen. What had happened was that the tripping line had twisted round and round itself until it was as stiff and unwielding as a metal spring and that this metal-like mess had ensnarled with it some of the shroud lines of the para-anchor. (The latter had not opened - had just lain in the water like a lump of cloth). Later, on arriving at a harbor near Cadiz when I was able to put it all out onto a dock and try to disentangle it, I found I had to cut away the tripping line - it had practically fused into a couple of "springs." These had abraded 11 of the 12 shroud lines and had indeed broken three of them. I knew I should return it to the factory [for repairs] but I did not dare let it out of my hands. I knew I would need it again and I intended to use it again. So I took it to a local sailmaker, spread it out on his floor and we agreed as to how to repair it. He sewed some very strong sailmaker's tape into the shroud lines, restoring them all to a good state and ensuring that they were all the original length.

On Christmas day we left again for the Canaries. Same story. Weather got bad, decided to put out the para-anchor and this time to do so before dark. I had bought a new tripping line, 50 metres of floating line. This went out OK, then the float buoy.... Got the float out and the parachute. Absolutely brilliant! The bow came right round into the waves and yawed from side to side, but I could see the parachute had opened. Good, so far, I thought. I then uncleated the pickup buoy, stood up and tossed it into the sea over the pulpit. I had cleated off the anchor rode at about 20/30 metres, and was going to let more out in progressive lengths. However, I never got as far as that because in a twinkling the parachute had opened, the rode-tightened to steel-bar tautness, and, horror of horrors, not only was it leading OVER the pulpit, which folded down as if made of butter, but it was also once round the forestay and my precious furling gear. How that happened I have next to no idea because I thought I had been very careful... I think this story illustrates the dangerous effect of being tired and maybe also of being short-handed.

OK, still enough daylight, probably, to winch it in and start again. However, we were hampered by the weather conditions from doing anything at a reasonable sort of speed. Rain, like a dense monsoon, fell like rods of iron, flattening the sea, doing a sort of white-out and flattening me too! Eventually got the chute back on deck. Exhausted. And dark now. OK, why didn't I motor up to the pickup buoy and pick it up? Because as I hadn't stitched the damned knot up, just tied it to the [float-line] swivel, it had come undone and is now floating happily around the north Atlantic, trailing its new rope!

Well, it was dark, I was soaked and exhausted, and felt unable to sort out the mess of lines, so bungeed it all away and off we went into the night and Force 7/8 - increasing - big seas, 4-6 metres. Later the night turned into a nightmare. I was making very poor progress with small sails, only about 2 knots, and a ship (whose Officer on Watch was clearly not on watch as I even fired a flare) collided with us! In order to prevent the mast from falling (an upper shroud was torn away) I decided to go back - 200 miles - to Cadiz. I think I am lucky to be alive, as after that the wind increased to 40+ kn steadily, gusting up to 55, and we had to hand-steer under the most minute sails, in waves that must have been 8-10 metres high....

Somehow - by hook or by crook - Eleanor managed to outdo Neptune and bring her ship back into safe harbor at Cadiz, whence she contacted Victor Shane. Shane then passed her feedback on to Don Whilldin of Para-Tech Engineering in Colorado.

Although it would appear that in this case the para-anchor and float line assembly may have been fouled even as they hit the water, Whilldin nevertheless went to work on the design of the Deployment Bag, to see if there was any way in which he could somehow further reduce the chances of float line foul-ups. The simplest solution, of course, would have been to forego the float-line altogether. Unfortunately the float line and float are necessary to keep larger para-anchors from sinking straight down when the wind dies.

So Whilldin made a modification to the deployment bag instead. The thirty feet or so of colored float line, previously coiled outside the Deployment Bag, is now tucked into a "kangaroo pouch" under it. With this minor design change there is less chance of float line foul-ups. Whilldin reasons that once the parachute has opened up and is under stable tension the chances of float line foul-ups are greatly reduced. Likely most of those foul-ups occur in the pre-inflation stage, when the parachute is a shapeless mess of loose cloth and shrouds.

Don Whilldin sent the English lady stranded in Spain a brand new sea anchor, in appreciation of her contribution to design improvement. The redoubtable Eleanor Tims has since crossed the Atlantic.

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!