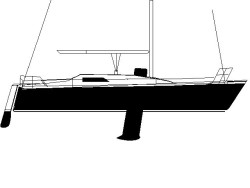

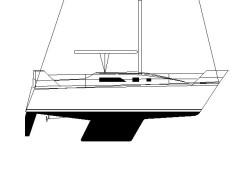

Fast 40 Sloop

40' x 3 Tons, Lifting Keel

12-Ft. Dia. Sea Anchor

Force 7-8 Conditions

File S/M-35, obtained from Robert J. Bragan, Bethesda MD. - Vessel name Javelin, hailing port West River - Fast 40 sloop, designed by Alan Adler, LOA 40' x LWL 36' x Beam 8' x Draft 7.5' (with keel down) x 3 Tons - Lifting keel (fiberglass-encapsulated 2000 lb. lead bulb on end) - Sea anchor: 12-ft. Diameter Para-Tech on 300' x 5/8" nylon braid rode with 1/2" stainless steel swivel - No trip line - Deployed in a gale in deep water about 300 miles west of Bermuda, with winds of 30-40 knots and seas of 12-15 feet - Vessel's bow yawed 30° with riding sail on backstay - Drift was about 5 n.m. during 12 hours at sea anchor.

An ultralight ocean racer designed by Alan Adler, this yacht was one of fifteen Fast 40's built in the 1980's by North End Shipyards of Rockland, Maine. Given her narrow beam, slender profile, low displacement, and high-tech construction, she was aptly named Javelin by her owner.

En route to Bermuda in May 1996, Javelin ran into bad weather and hove to a sea anchor. After the weather moderated she got underway again. And that's when her 2000 lb. lifting keel fell off. The yacht rolled over and subsequently had to be abandoned. Rob Bragan's brief hand-written note on the back of the DDDB form reads, "the 12 ft. sea anchor performed beautifully once anchor riding sail set on backstay."

The following is a transcript of Rob Bragan's article about the incident, appearing in the September/October 1996 issue of Ocean Navigator (reproduced by permission of Ocean Navigator Magazine):

We sailed Javelin extensively on the [Chesapeake] bay in all sorts of weather, including winter gales. Experience caused us to add stand-up blocks on the cabin top for double-sheeting the trysail, as well as a 12-foot Para-Tech sea anchor, a wind vane self steering system, anchor riding sail, detachable furling system for the Yankee jib, and many other improvements. In two years I hauled the boat twice, initially for a survey that found no problems and later to fair and paint the keel and hull. The keel assembly [2000 lb. fiberglass encapsulated lead bulb] was inspected each time, but only after losing Javelin did I learn that the previous owner had found broken bolts among those that secure the Delrin blocks and had replaced all four bolts twice. (A good maintenance log might have saved the boat by recording such details for subsequent owners).

On Friday, May 24, 1996, after picking up a rented Viking life raft and an ACR Type B 121.5/243 MHz EPIRB (406 MHz units cannot be rented) from Outfitters/USA services in Annapolis, we left our mooring in Galesville, MD....

Transitioning from Chesapeake Bay sailing to ocean sailing as night fell, we left the coast behind. Our course of 150° magnetic led to a waypoint NE of Cape Hatteras where the [Gulf] stream was only 80 nautical miles wide.... A pod of 30 to 50 spotted dolphins greeted us as we entered the stream, and they stayed until a tail slapped to starboard calling them off to the south. Were they moving away from impending bad weather?

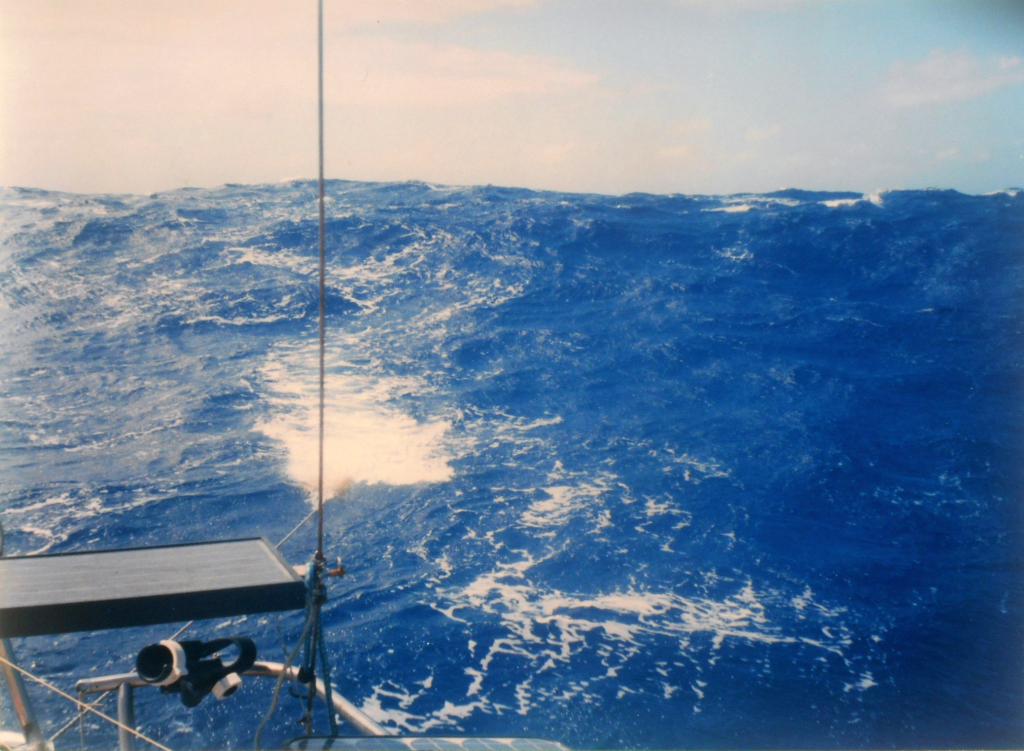

The wind strengthened from the NNE on May 30, reaching a sustained 28 to 32 knots (Force 7) at the masthead anemometer by afternoon. The sea state increased from a few feet in the morning to 10 to 15 feet with occasionally larger, breaking waves, by evening. The 65° water temperature, knotmeter, and GPS readings all suggested we were in the wrong quadrant of a cold eddy which was aggravating the sea state. We put the second drop boards in place, secured the sliding hatch and hand-steered a beam reach, turning up and over bigger waves. The back sides of some waves were as steep as the fronts, requiring another turn at the wave top to set a good angle down the back and avoid slamming the boat....

After battling the waves for hours, the prospects of further exhausting ourselves with hand steering or deploying a drogue and losing miles by running off to the SSW were unacceptable. Lying ahull or heaving to were out of the question since Javelin had been too lively in past attempts and since the steep, breaking waves could roll the boat if she were caught broadside. Our position was approximately 400 miles from Bermuda, 10 to 20 nm south of the rhumb line. It was the right time to deploy the sea anchor. I had made up a dual-purpose sea anchor/drogue bridle of 3/4 inch three strand nylon line a few weeks before that would be strong and resist chafe. The bridle, shackled to stainless steel lifting plates on the aft end of the keel case, ran forward and through the rubber bow anchor rollers, terminating in a heavy thimble clamped in place. Three hundred feet of 5/8-inch braided nylon anchor rode was now shackled between the bridle thimble and the sea anchor. Strong attachment points on the boat, chafe protection, and a long, braided elastic rode are necessary components of a sea anchor system.

Deployment involved Tim's steering us through a 150° turn to point up into the wind, at which time I fed out the sea anchor float, trip line, deployment bag, and rode from the bow. The boat immediately fell off onto port tack before Tim could drag the trysail down. I fed rode and Tim wrestled sail until finally the rode came taught and we were pulled around.... A few minutes after the messy set, we were riding to the sea anchor and Javelin began her anchor dance. She was sailing through a 90° arc, so that breaking waves threatened to throw her sideways.... Setting the 15- to 20 square-foot anchor riding sail on the backstay with double sheets led forward to the toerails reduced the boat's arc to less than 60°.... With the cockpit secured, we closed ourselves up inside the boat to rest. Both the boat and we had taken a pounding during the last 12 hours. We needed food and sleep....

The next day and a half brought NE winds at 18 to 25 knots and six-to 10-foot seas, so we recovered the sea anchor and set sail that day, continuing on through the night making good speed and staying on course. We lay to the sea anchor on the night of June 1 as the wind clocked to east and strengthened. On June 2 we again set sail, but 20 to 30 knots of wind out of the ESE nearly halted our progress, and we made only 40 nm to the south. Early that evening we again set the sea anchor to hold our position while awaiting a better wind direction. Sounds from the keel that were louder than usual caused Tim to raise it into its case for support....

We awoke on the morning of June 3 to the first beautiful day of the trip. The wind had rounded to the SW at last and moderated to 10 knots. The sky was clear for the first time, the waves were running three to five feet and we only had a couple of hundred miles to go.... We lowered the keel and put the aluminum brace back in place.... Upon recovering the sea anchor, we raised the mainsail. As it filled, the boat heeled a little... a lot... and continued to lay over until flat on her side. It happened so gently.... After pausing for a few seconds, Javelin finished turning turtle, leaving us alongside trying to comprehend what had happened in less than a minute. We climbed onto the hull and peered into the empty keel case. The four bolts that had secured the keel to the Delrin blocks on either side were sheared off, leaving the heads on one side, tails on the other, and nothing but air in between....

After getting over the initial shock, Rob Bragan and son Tim inflated the life raft and quickly resigned themselves to the serious business of survival, diving and retrieving 20 gallons of water, food, blankets etc. from Javelin's upturned hull. The EPIRB was then turned on and the raft allowed to drift free of the mothership.

A short while later they spotted a passing ship and fired off parachute flares, but it did not see them. Just before sunset however, a Coast Guard C-130 roared overhead. Crew members on the aircraft reportedly saw Javelin's upturned hull first, and Bragan reckons that they should have remained tethered to the hull for as long as possible to be easier to see. Later the Italian bulk carrier Ursa Major was diverted to the scene and plucked the waterlogged sailors out of the Atlantic.