S/M-25

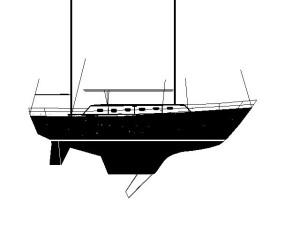

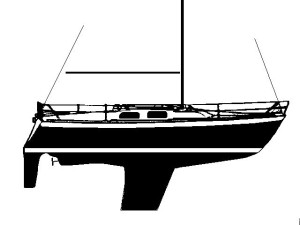

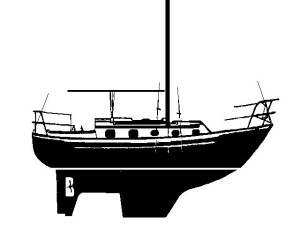

Valiant 40 Cutter

40' x 14 Tons, Low Aspect Fin/Skeg

28-Ft. Dia. Parachute Sea Anchor

Force 10-11 Conditions

File S/M-25, obtained from Jim & Lyn Foley, San Lorenzo, CA. - Vessel name Sanctuary, hailing port Alameda, Valiant cutter, designed by Robert Perry, LOA 40' x LWL 34' x Beam 12' x Draft 6' x 14 Tons - Low aspect fin keel & skeg rudder- Sea anchor: 28-ft. Diameter C-9 military class parachute on 300' x 5/8" nylon three strand rode with 1/2" stainless steel swivel - No trip line - Deployed in a storm in deep water about 300 miles north of Bermuda with winds of 55-70 knots and seas of 24 feet - Vessel's bow yawed 20° - Due to the Gulf Stream drift was 15 miles to windward in 4 hours.

Sanctuary, a sea-kindly Perry-designed Valiant 40 was en route to the Azores from Florida when she ran into a northeasterly storm in the Gulf Stream. The stream was flowing exactly contrary to the wind at a current speed of five knots! One can only imagine the hell that Sanctuary must have gone through on the night of 28 May 1995. Transcript:

While crossing the Atlantic in May 1995 we encountered a Force 10 storm, an occurrence we will never forget nor care to repeat. Sailing east at approx. 38° 45' N, 63° 58' W, we enjoyed the fast moving east setting current and warm waters of the Gulf Stream. Dolphins played in our bow wake, tunas were jumping and the birds were fishing. With hardly a breath of wind, we attributed most of Sanctuary's forward progress of 6.5 knots to the Gulf Stream.

The morning weather report from NMN (Norfolk, VA) included gale warnings for 40° north, 60° west, with forecast winds of 35-40 knots, seas 14-16 feet. The gale was indicated moving ENE at approx. 15 knots, and had a 200 miles semi-circle of influence to its southeast. In other words, we were some 75 nm behind the gale, and proceeding towards it at about 6 knots [while it was moving away at 15 knots]. We plotted the parameters of the Gulf Stream as reported by NMN. The stream's main body was moving northeast above 40° N, and then curving back down to 39° N, creating a bend or bight in its eastward flow. While we realized that we were sailing into the lower semi-circle of the gale, we hated to give up the favorable current and thought we could ride the tail feathers of the forecasted gale as it moved forward of us. It did not occur to us that the gale would stall in the bight of the stream and build to storm force before the day was out.

Early in the afternoon a northeast swell began to rise and fall with no wind to show for it. suddenly the blue sunny skies disappeared, winds picked up to 25, then 30 knots, increasing steadily. Seas had risen by that time to 10-12 feet. Accordingly, we kept busy reefing down our full flying sails, until we carried our smallest storm sail plan - a triple-reefed main and a storm staysail.

As conditions worsened we hove-to using the two sails, thinking the "gale" would move eastward. We planned to sit tight until it passed - but the Gulf Stream current held us in the trough more than our sails could hold us into the steep, confused, falling and breaking seas. Then the northeast wind increased to a dramatic 55 or more knots. At the crest of waves Sanctuary would round up, get knocked back and over. We had one very dangerous Chinese jibe - a wave broke on us, knocked our stern around and the cockpit filled with green water.

We decided to lower the sails and set the parachute sea anchor. With 55 knots and more of wind, it was a challenge to get the sails down. As Jim struggled on the wheel, Lyn managed to douse the main and staysail, staying on the deck thanks to harness and tether. We then deployed the 28-ft. diameter C-9 military parachute - with 1/2" stainless steel swivel and 300' of 5/8" three strand nylon rode. The rode was led from the port side bulwarks hawsepipe, aft to the primary winch and cleat.

We deployed the parachute to windward, with no problem, but the line went taut so fast and so tight that we couldn't get the double-lined fire hose chafe gear in place. We tried motoring up on the anchor to relieve pressure - but with 55 knots of wind on the nose, and the parachute in 5 knots of opposing current pulling us INTO the wind and waves, we couldn't get the rode to slacken. We were unable to uncleat and unwind the rode from the winch, slip the chafe gear on, rewinch and recleat it. The rode was so taut instantly that we could see the 3-strand 5/8" nylon reducing in diameter. It was stretching down to 1/2" or less. We felt the rode wouldn't last long, and carefully stood clear of the line.

This line was brand new, never used before, dedicated to the para-anchor. We held 30 feet of the bitter end in the cockpit in reserve, and let out about a foot every 20-30 minutes to combat chafe. Meanwhile, as we worried about chafe, the para-anchor was working beautifully. The boat rode up the face of the waves, punching through their tops as the huge seas rolled under us. No more green water came on board, no more near knock-downs. For four hours we rested below, taking turns watching and letting out the rode to combat chafe. But in spite of our efforts the line parted after an especially strong gust, and the sea anchor was gone.

We fearfully lay a-hull until first light, then turned and ran before the waves, towing warps in an attempt to break up the curlers before they broke on us. We trailed 300 foot lines, with fenders and heavy gear in their bights. Lyn stood and looked aft, watching the waves and warning Jim as he steered down their faces. We were pooped several times in the next few hours. The seas were too strong for Lyn to steer, and we were both exhausted. Luckily, a few hours later we broke free of the Gulf Stream and the storm moved on.

We heard officially on that morning weather broadcast from NMN that the "gale" had been upgraded to a Force 10 storm, carrying winds up to 70 knots. We don't believe we experienced winds that high, however, using our stern-mounted radar arch as a measure, we know we had seas of 20 feet.

What we learned: When we heard the gale forecast, we should have changed course to leave the Gulf Stream and its five-knot current. We believe the rode parted because: 1) The parachute was too big for our boat - that the current actually pulled us forward at more than 3 knots, instead of actually stopping the boat or truly "heaving-to." 2) No chafe protection on the rode. 3) Unusual circumstances of extreme current and opposing seas and winds.

We will purchase a smaller diameter parachute. We will use 600 feet of 7/8" nylon line for the rode. Since the incident we have read Lin and Larry Pardey's Storm Tactics Handbook and discussed what happened. Due to what we learned from them and our experience, we plan to add a bridle as they describe, with a snatch block over the rode and a turning block at the bow - and have heavy duty chafe gear in place before deployment.

It is Victor Shane's considered opinion that if Sanctuary had deployed the given parachute on a much longer rode, with adequate chafe gear, this might have been one of the most remarkable files in the S/M section of the Drag Device Data Base. In some respects it still is.