Camper Nicholson Sloop

35' x 7.5 Tons, Low Aspect Fin/Skeg

15-Ft. Dia. Sea Anchor

Force 7-8 Conditions

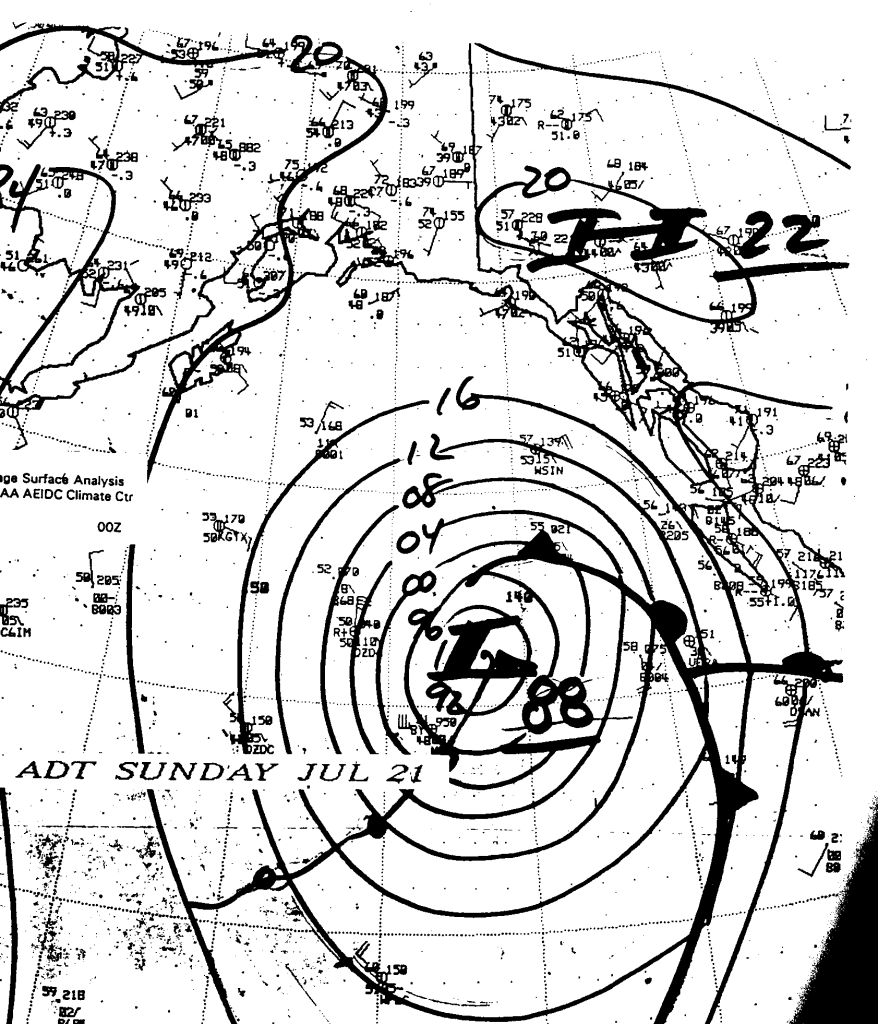

File S/M-28, obtained from John G. Driscoll, Holywood, County Down, UK - Vessel name Moonlight Of Down, hailing port Southampton, Camper Nicholson sloop, designed by Raymond Wall, LOA 35' x LWL 24' x Beam 10' x Draft 5'6" x 7.5 Tons - Low aspect fin keel & skeg rudder - Sea anchor: 15-ft. Diameter Para-Tech on 380' x 5/8" nylon braid rode and 60' of chain, with 1/2" stainless steel swivel - Partial trip line - Deployed in a low system in deep water about 300 miles WNW of Bermuda with winds of 30-40 knots and seas of 12 feet - Vessel's bow yawed 30°.

UK sailor John Driscoll learned some lessons about the use of the Pardey bridling system when he crossed the Atlantic in November 1996. He offers the reader some valuable advice about having a game plan - and practice time:

Our vessel Moonlight Of Down was on a passage from Newport, Rhode Island to Bermuda, manned by myself and my wife. At 2200 hrs 1 Nov 96 the vessel was hove-to under triple reefed mains'l in a SW Force 7 wind with a rough sea, as it was not possible for the off-watch crew to sleep when underway. By 0000 hrs 2 Nov it was blowing SW Force 7-8 as a trough or local low center passed by. It was decided to deploy the Para-Tech sea anchor. This had not been attempted before, but practice runs of the deployment procedure had been carried out to the point of dropping the DSB [deployable stowage bag] overboard,

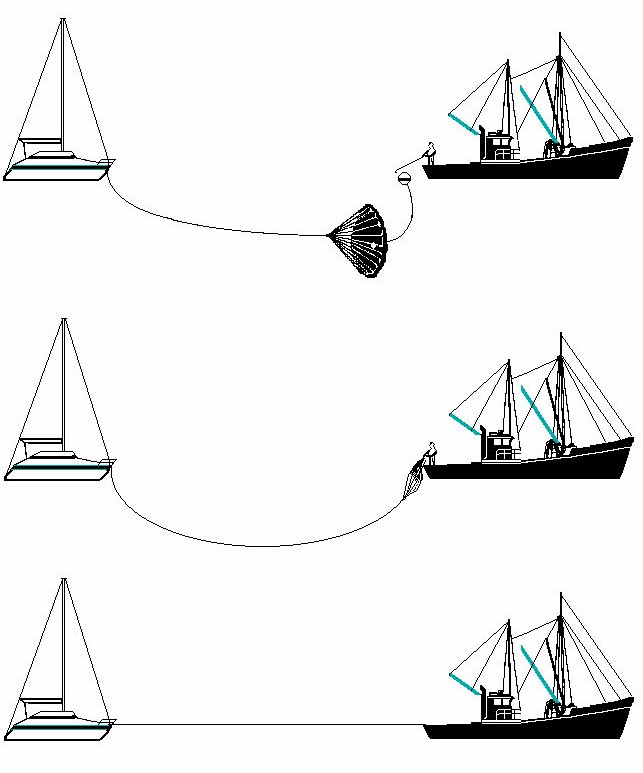

The drill calls for the 5/8" octo-plait [8-ply braid] rode to be passed forward from the cockpit - outside everything - and shackled onto the shank of the 33 lb. Bruce, main bow anchor. 20 Meters of chain is then run out. A "Pardey Bridle" is rolling-hitched to the chain, and a further 10 m of chain run out. The parachute buoy, tripping line, primary float, float line, DSB and the main part of the 120 m nylon rode are then deployed from the safety of the cockpit.

The drill went perfectly, no problems, and the vessel lay at 50° to the wind on the starboard tack with some tension on the bridle. The vessel then tacked and lay with the bridle under the boat. The vessel tacked every ten minutes or so. It was decided that the weight of the anchor and chain were too great for proper bridling (angles wrong), so some chain was reversed and the bridle re-attached. No improvement. At 0430 it was noted that the wind had dropped to Force 6 so it was decided to lay without a bridle, head to wind - so the crew could sleep.

A rapid, severe roll developed with the vessel occasionally tacking about 30° each side of the wind. Sleep, or even rest were completely impossible, and it was decided to recover the sea anchor at first light, by which time the wind had dropped to Force 4.

The anchor was brought aboard with the windlass. The vessel was motored up the rode, which was recovered by hand to within 30 m of the sea anchor. The vessel was maneuvered to the parachute buoy, which was recovered and the sea anchor picked up by the partial trip line over the starboard bow. It came aboard so well-arranged it was immediately re-bagged for re-deployment if necessary.

In spite of the Hydrovane Self-Steering rudder being lashed amidships the vessel had at sometime backed down with sufficient force to free the rudder and stock hard over within the head clamp. No other damage or chafe occurred. Whereas the procedures for deployment and recovery were completely successful, the method of utilization was not considered successful and will have to be modified.

The following points are considered significant in the failure to achieve a satisfactory set: 1) Lying to a sea anchor off the bow head-to-wind is not considered practical due to the violent rolling induced. 2) Attaching the nylon rode to the sea anchor and dropping it over the bow, although improving the catenary and avoiding chafe, does not allow a Pardey Bridle to be used effectively on this vessel. 3) A sea anchor cannot be considered an effective asset unless practice runs have been carried out in suitable conditions to determine the exact method of utilization.

My next attempt (a practice run) will be to deploy the sea anchor as described in Storm Tactics as shown in diagrams E & F (pages 38 & 39) and photos 3 & 4 (pages 79 & 80). I feel that the rode and bridle should be in the approximate plane of the vessel's gunwale to be effective. They should not lead steeply downward as occurs when chain is used off the bow. Should chain need to be incorporated into the rode it would probably be best at the sea anchor end. In conclusion we feel that the Para-Tech sea anchor is well constructed and its drag characteristic will enable it to achieve the desired performance, once we have developed the method of utilization appropriate to our own vessel.