D/M-19

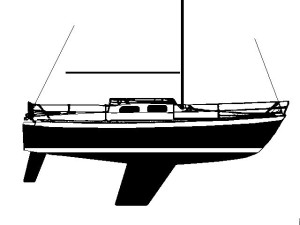

Monohull, Sparkman & Stephens

39' x 8 Tons, Fin Keel

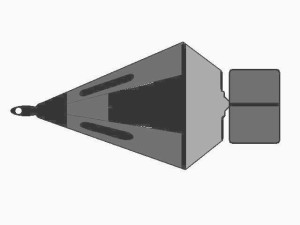

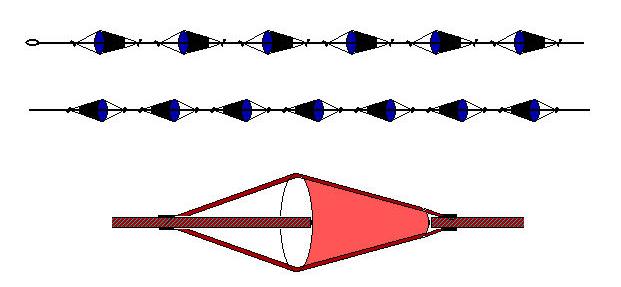

Seabrake MK I

Force 10+ Conditions

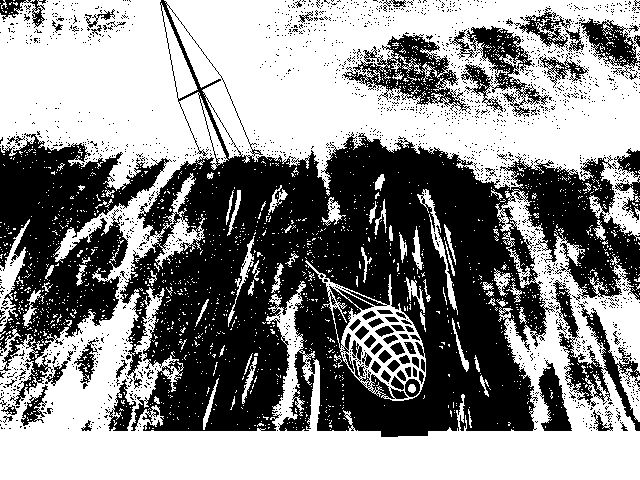

File D/M-19, obtained from W.R. Allen, Milson's Point, NSW, Australia - Vessel name Adele, hailing port Sydney, monohull, Superstar sloop designed by Sparkman & Stephens, LOA 39' x LWL 35' x Beam 12' x Draft 6' x 8 Tons - Fin keel - Drogue: Seabrake MK I on 200' x 5/8" nylon braid rode - Deployed in cyclone Bola in deep water about 50 miles NW of the North Cape of New Zealand with winds of 60 knots and seas of 40 ft. - Vessel could be steered through a wide arc in the proximity of land - Speed was reduced to about 3-5 knots during 36 hours of deployment.

The Seabrake used in this file was the same model used by Peter Blake in D/T-1, the more expensive MK I, with the spring-loaded gate mechanisms. The mechanism is adjustable and can be set to open the gates at a certain speed, instantly increasing drag by about 70%. Refer to inventor John Abernethy's explanation of the workings of the spring-loaded mechanism in File D/M-10. The earlier versions (likely this one) had ballasted nacelles to help keep them submerged, while later versions relied on a length of chain in the rode. Transcript:

Since purchasing the Seabrake I have made four Tasman crossings - Sydney to Auckland and return. The first two crossings were reasonably monotonous. The third included my involvement as a competitor in the Trans Tasman Transfield Challenge Race [Feb/March 1988]. In this race competitors were savaged by cyclone Bola in the vicinity of Three Kings Island and the North Cape of New Zealand. We ran into Bola on the approaches to the northern tip of New Zealand. There was no race warning and the first advisory we had was a weather forecast from a shore-based NZ radio station! Needless to say this warning was passed rapidly through the fleet! We passed through Bola whilst it was centered in the area of Three Kings Islands, Cape Reinga and North Cape. Retrospectively the weather maps indicated that Bola had three centers concentrated in the area at the time.

We had to make an important decision regarding our course across the top of NZ, a particularly treacherous piece of water in bad weather. Even in settled weather the NZ pilot advises that small vessels should approach no closer than fives miles to land. In rough weather fishing boats and even large vessels have been lost, in some cases without trace. This is largely due to strong currents flowing up and down the West and East coasts, and shallow waters (120-130 meters). In bad weather the safer course is to keep northward of the Three Kings and proceed via the Three Kings Trough in deep water (more than 1000 meters). This is the course we adopted.

At 2200 hrs on the 7th March at 33° 36' S, 169° 17' E, we were under bare poles and had set the Seabrake. Shortly thereafter we suffered a 90 degree knockdown, but apart from a few bruises there was no damage. However through this incident we were made very much aware of the confused nature of the seas and that we were catching the odd rogue cross sea. On the 8th, 9th and 10th March we proceeded in a SE direction following the Three Kings Trough, towing the Seabrake. During this period of heavy breaking seas with winds in excess of 60 knots the Seabrake was in continuous use, doing a marvelous job steadying our progress and giving us a strong feeling of security regardless of the conditions. At no stage did Adele show any tendency to broach and it was always possible to maintain a measure of control, despite the extreme conditions.

With the wind generally NW we streamed the Seabrake from the starboard primary winch, which meant the brake was mainly on the quarter, though when the occasion demanded with a particularly big sea we would run straight before. I am not aware of any period when the brake was not on the back of the next wave. On the crest of a wave we would occasionally pull the brake clear [out of a wave face] but it always dug in to hold us for the next one. We made no adjustments to the spring-loaded mechanism which was set to operate [kick in and generate 70% more drag] at 5 knots, and generally we were able to maintain that speed.

We had no problems with chafe and we did not use chain or any other means to weigh the brake down. Wind speed was variable between 40 and 60 knots and for shorter periods 60 plus. Difficult to estimate the height of waves. With a fifty odd foot mast we would on occasions be buried in the trough. On the 8th we had periods of heavy rain followed by gusty winds up to 50 kts. On the 9th with storm jib set the log says "from midnight to daybreak ran before heavy breaking seas - Seabrake probably saved us from being rolled in the early hours of the morning. During the day and evening conditions too rough to get sailing so jilled along at 2-5 kts under Seabrake in a SE direction away from North Cape." On 10th March conditions had moderated and we were able to proceed under full sail.

On the return journey, Auckland to Sydney, we experienced peak conditions. A high extended right across the Tasman with a broad front covering most of the North Island of New Zealand with a narrow front bordering the New South Wales coast [of Australia]. We left New Zealand in extremely light conditions having to motor up the East Coast until we cleared the Three Kings. Thereafter we moved in an easterly air flow right across the Tasman.

As we approached Australia the wind steadily increased. This was further exacerbated by low pressure areas developing north and south of the high. During the last five days we experienced winds in excess of 40 knots for most of the time, including a squall which lasted about an hour which was an absolute white out of wind-driven seas, which we estimated in excess of 100 knots.

Throughout the period of five days we towed the Seabrake off the weather quarter. Initially we sailed under trysail and boomed out storm jib. As conditions increased in severity we progressively lowered the trysail then the storm jib. Later the cockpit spray hood and life buoys, to reduce windage. As you can imagine, with an easterly air stream extending right across the Tasman the seas built up and were breaking dangerously, particularly at times when the winds reached about 50 knots. Adele handled the conditions extremely well with the Seabrake out. It was quite remarkable how in the midst of a breaking wave it would hold the boat momentarily and allow the wave to sweep forward and away from under us.

As you will have gathered from this I have the highest regard for the Seabrake. Even under the worst conditions the brake always gives a measure of control and at the same time enables you to make progress. Not the least virtue is a sense of security and a great boost to your confidence at time when your morale could be at low ebb. The downside is that they are comparatively heavy and they take up room in the cockpit, though this can be overcome to some extent by mounting them on special brackets [on the stern pulpit]. Still, for safety at sea, anything is worthwhile.

I have also had some experience with parachute anchors which are also great, particularly with prolonged periods of heavy weather when you want to get some sleep and rest up for a period. You can really sit back and enjoy a good storm! The main problem is with chafe and this needs constant attention.

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!

S/T-3

S/T-3