S/M-40

Monohull, Alden Ketch

50' x 15 Tons, Full Keel & Cutaway Forefoot

18-Ft. Dia. Sea Anchor

Force 9-10 Conditions

File S/M-40, obtained from Steven McAbee, Lihue, Hawaii - Vessel name Celtic, hailing port Dutch Harbor (Alaska), monohull, cruising ketch designed by John Alden, LOA 50' x LWL 33' x Beam 12' 6' x Draft 5' 6" x 15 Tons - Full keel & cutaway forefoot - Sea anchor: 18' Diameter Para-Tech on 400' x 3/4" nylon three strand rode and 150' chain, with 5/8" stainless steel swivel - Deployed in a whole gale in deep water about 500 miles south of Dutch Harbor with winds of 45-50 knots and seas of 20-25 ft. - Vessel's bow yawed 10° with reefed mizzen flying - Drift was about 22 n.m. during 5 days at sea anchor.

Celtic is a 45-ft. center cockpit ketch built by Fuji Shipyards in 1975. In June 1996 she left Dutch Harbor, Alaska, headed for Hawaii and the South Pacific. On board were owner Steven McAbee, wife Pamela and son Zach. A few days out they ran into a succession of gales in the Gulf of Alaska. McAbee was well-prepared and deployed an 18-ft. diameter Para-Tech sea anchor. Celtic spent the next five days at sea anchor, her heavy, reefed mizzen keeping her bow nicely snubbed into the seas. The following is a transcript of Steven McAbee's article Crossing Gale Alley, appearing in the November/December 1997 issue of Ocean Navigator Magazine (reproduced by permission):

We had fully expected gales and had made preparations for them. Up on the bow, ready to deploy, was a Para-Tech sea anchor complete with trip line, buoys, 3/4-inch rode, and chain catenary. In the lazarette we had stowed a Seabrake Drogue with its own dedicated rode/catenary and bridle. We had Mustang exposure suits for foul weather on deck, harnesses and snap lines for each of us, immersion suits for abandon ship, flares, handheld VHF and GPS, survival supplies, and a 406 EPIRB. We also had Celtic, a proven storm survivor.

Nevertheless, as the low continued to deepen and it became apparent that we would have to deal with it, an old familiar dread began to live in my guts. How bad would it get? Would the sea anchor and drogue work? Although we had practiced deploying them, it had been in relatively calm conditions. We were 500 miles from the nearest land and out of the shipping lanes on a big and lonely ocean. There would be no help coming. Whatever happened, we would have to deal with it ourselves. At night we listened on the SSB to other vessels, some in distress. A 49-foot ketch 400 miles south of Adak lost her rudder and was pummeled by 25-ft. seas. Kamishak Queen, a vessel we were familiar with, sank in Nuka Bay. A tripped EPIRB had been detected in Bristol Bay. The weather forecast called for 45-knot winds and 25-ft. seas. If the low stayed on track we would be in the worst possible place: south of the center and on the backside, the zone of highest wind and seas.

Throughout the day the winds and seas increased. As the wind shifted around from northwest to west to southwest and then south, our progress slowed until we found ourselves beating into 30-knot winds and eight-foot seas. The time had come to make a major strategy decision: Should we bear off to the west or east and try to make a few miles of southing in the worsening conditions? Or would it be better to deploy the sea anchor and sit out the gale?

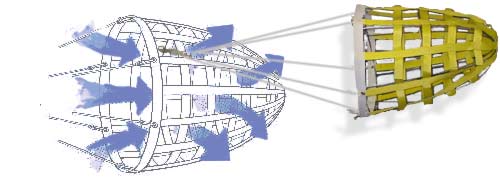

After due consideration, we decided to use the sea anchor. The Para-Tech was connected to 400 feet of 3/4-inch nylon rode with a stainless steel swivel. All rode ends had spliced eyes with steel thimbles, and in the middle of the rode we had spliced in 20 feet of 1/2-inch galvanized chain to act as a catenary. After a practice deployment before the trip, we had decided to connect the bitter end of the rode to the chain anchor rode and deploy 150 of that. Additionally, we lashed the anchor chain to the bow roller to prevent it from jumping out as Celtic rode the waves into the trough.

We had packed the sea anchor, trip line, and rode into a large canvas bag and lashed it to the bow rail with the bitter end hanging out a hole cut in the bottom. All we had to do was unlash the bag, shackle the bitter end to the anchor chain (the [steel] anchor had been disconnected and stored below for the open ocean), attach the buoys to the trip line, and let her go. Everything went smoothly, and soon we were securely moored to the Para-Tech. We hoisted a reefed mizzen, secured everything on deck, and went below. As night fell we began to feel the full fury of the storm. The rising wind was blowing a steady 40 knots, gusting to more than 50, while the seas built.

I was really pleased with the performance of the sea anchor and the way Celtic rode. During the five days of gale winds at 40 to 50 knots and seas of 18 to 25 feet, I never felt we were in any immediate danger. As the storm worsened and seas began to break over Celtic, I began to wish I had some way to attach all that chain and rode to the bobstay eye on Celtic's stem so her bow would ride higher, but there was no changing anything once it was set. As each monster wave approached, Celtic would back up, much like a retreating Muhammed Ali against a charging Joe Frazier, and let the impact roll under her. Huge waves would break on us, darkening the cabin as green water rolled over the ports.

We were alone. We thought about all the stories we'd heard about vessels slowly breaking up under similar onslaughts: seams opening, through-hulls loosening, cockpit drains plugging. We had made all the preparations we could; all we could do was remain alert and deal with whatever happened.

We set up a radio schedule with the Kodiak Coast Guard Communication Base, better known as CommSta Kodiak, and every four hours we gave them our position, weather conditions, and vessel status. It was a comfort to speak with someone, and the sound of the radio operator's voice and the obvious concern of everyone at the station about our safety was really comforting.... By the time the storm abated, we'd had our fill of granola bars, crackers, and pop. We'd also had our fill of gales. For the last week it had been hard sleep, except for Zach, who was unflappable and able to sleep while weightless and bouncing off the ceiling. We were exhausted.

Unfortunately, the weatherfax showed another developing low headed in our direction, and we decided to make a run for it. The wind had switched around to the west but had dropped to near calm. I proposed that we fire up the engine and run south for 48 hours. That would get us about 300 miles farther and hopefully get us out of what we had come to refer to as "gale alley." Pamela and Zach both agreed, and in short order we were underway.

Forty-eight hours later, on July 8, 13 days after leaving Unalaska, we shut down the engine for the last time. We estimated that we had about 10 gallons of fuel left, and we had consumed much of our perishable food supplies. Counting four days in English Bay and the five days hove to during the gale, we had spent a total of nine days going nowhere. We still had a long way to sail, so after considering everything, we decided to head for Hawaii, where we could re-supply and recuperate before going on to the Marshall Islands. With the wind out of the west and Hawaii just 1,200 miles due south of us, we suddenly felt eager and optimistic....

Twenty-seven days after casting off from Dutch Harbor, Celtic entered Nawiliwili Bay on the southeast corner of the island of Kauai.