D/M-10

Monohull, Charter Vessel

35' x 15 Tons, Long Keel

36" x 12" Cylindrical Device

Force 12 Conditions

File D/M-10, obtained from John Abernethy, Woollahra, Australia - Vessel name Papeo, hailing port Port Fairy, monohull, charter vessel, LOA 35' x Beam 10' x Draft 6' x 15 Tons - Long keel - Drogue: 36" x 12" Diameter stainless steel calf bucket on 100' x 1" nylon three strand rode - Deployed in a "Southerly Buster" storm in shallow water (15 fathoms) near Lady Julia Percy Island (Bass Strait) with winds of 100 m.p.h. and seas of 50 ft. - This event led to the genesis and development of the Australian Seabrake drogues.

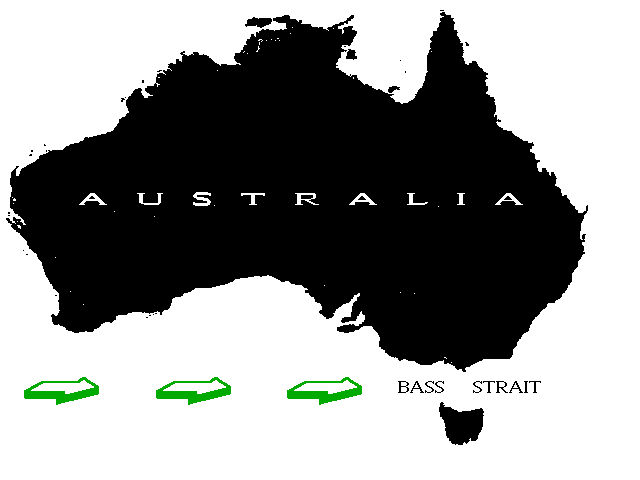

Seabrake was born in the Australia's notorious Bass Strait, as treacherous a body of water as one could wish for. The Bass Strait is a 170 mile wide gauntlet that divides the Australian mainland from Tasmania. It has claimed thousands of lives. The roaring forties and mature Southern Ocean waves roll in unabated all the way from Africa, and run headlong into this gauntlet. As they try to squeeze into the narrow Bass Strait they jump over the shallow Continental Shelf and undergo a metamorphosis that can only be described as a sailor's nightmare. Sudden storms can come up without warning, producing life-threatening conditions within hours.

Running before such steep and unstable seas is a little like barreling down muddy hills on a dirt bike without brakes. Imagine flying over bumps, skidding and careening sideways, somehow trying to keep the bike from falling out from under you, dirt and mud flying all over the place. If you can imagine all this, you will understand the logic and thinking behind the invention of the Australian Seabrake.

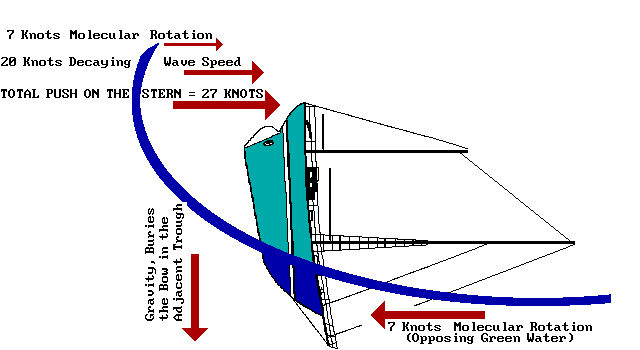

As a yacht is running down the face of such seas there will be times when the rudder will be ineffective. Because of orbital rotation and the movement of water on waves that are breaking, helm control will decrease on the crests, where it is needed most (see Figs. 7-10 and Fig. 49). As the boat is picked up and accelerated by a crest, the flow of water past the rudder is suddenly diminished and the helm goes limp. Small craft rudders are all but useless on the crests of breaking seas. If the boat is "captured" by such a crest and cannot disengage from it, the wave-induced yawing moment will be greater than the restoring moment available from the rudder and the result may be a broach, a capsize or even a 360° roll. This is where the directional restraint of a drogue (situated elsewhere on the wave train) is needed to help keep the vessel aligned, as well as to provide the drag needed to disengage the boat from the fast moving crest.

The incident that sparked the creation of Seabrake took place in 1979 - the year of the Fastnet tragedy. Abernethy's boat, Papeo, was on a charter, looking for great white sharks. She was anchored in the lee of Lady Julia Percy Island, some twenty miles from the Australian mainland, when a "Southerly Buster" came up. The wind quickly built up to hurricane force and in no time Papeo had lost all three of her ground anchors. With her engine started she began to make a desperate run for safe harbor on the mainland. However no sooner out of the lee of Lady Julia Percy Island than she was pummeled by mountains of fast moving white water. A cone-shaped sea anchor, several feet in diameter, was deployed off the stern as an emergency measure, but it slowed the boat down too much. She was squarely hammered by a breaking wave. This wave wiped her entire deck clean, breaking a number of items as well as ripping off the focs'le hatch and taking it out to sea. A miracle of sorts then occurred when three dolphins that had been seen in the vicinity of the boat swam to the floating hatch and pushed it back close enough so that Captain Abernethy could gaff it and bring it back on deck. With the hatch hastily reinstalled, Abernethy took the knife and cut away the rode to the sea anchor. Papeo was then picked up by another huge wave and sent hurtling down into the abyss-like trough. Instinctively, Abernethy reached for the only remaining item that could function as a drogue - a stainless steel cylindrical calf bucket. These calf buckets are commonly found on Australian farms and often used as bait buckets on Australian fishing boats. Abernethy attached some line, grabbed an axe and sliced open a few holes in the bottom of the bucket and threw it over the transom. This calf bucket, since dubbed "the most famous milk bucket in Australian maritime history," then took hold of the situation and produced the desired effect, both in terms of limiting Papeo's speed, and also in terms of keeping her attitude safely aligned with the seaway.

The ride was exhilarating, to say the least. Abernethy described it to Victor Shane as "a lazy elevator." The boat would be picked up, half rolled and carried along, but never thrown or overwhelmed or broached by the mountains of confused water. By sheer luck the restraint of the makeshift drogue was just enough to keep Papeo on an even keel throughout the ordeal. She was able to keep plenty of water beneath at all times and never even came close to falling off a wave, or burying her bow into the bottom of a trough. It was a defining moment. It left an indelible mark on Abernethy's mind and several years later he came up with the first prototype of the Seabrake drogue. Subsequent models underwent extensive tank tests in the Australian Maritime College, and Seabrake came to be. Abernethy's firm has since produced a wide variety of drogues for sailboats, powered vessels and even large ships and submarines. When Abernethy was in the United States Shane had the privilege of interviewing him in Los Angeles. A synopsis of that interview follows (by permission):

The development of Seabrake was preceded by ten years of commercial operation in Australia's Bass Strait. As a commercial fisherman and charter boat owner based in the most dangerous stretch of Bass Strait, I was routinely operating in heavy seas and often towing large game fish in them. I was frequently involved in Search and Rescue operations as well, towing various types of distressed vessels to safety. Typically, conditions involved combined seas in excess of 20 feet and sustained winds of 30 knots or more. On many outings I have encountered 50 ft. seas and 50 knots winds. The incident that occasioned the birth of Seabrake involved 80 ft. combined seas and winds peaking at 100 m.p.h. There were other factors that contributed to the development of Seabrake. Contact with many who have lost vessels in the Bass Strait in the past 40 years, for one thing. My own experience showing that "speed kills," and that conventional cone-shaped drag devices don't assist and in fact can be dangerous, for another. Moreover I have found that towing items such as large game fish, bundles of rope, etc. on a short warp can create too much drag and cause a "stall" at the wrong moment - the bottom of a trough. And towing them on a long warp does not always produce the desired effect either. Drag and restraint can vary from too much to too little, depending on the direction of pull and how much rope remains in the water.

From the above I endeavored to devise a drogue that could maintain a consistent ratio between speed and drag. Never is the statement "speed kills" more relevant than when applied to vessels running before strong following seas. Finding a happy medium is the key to success. Seabrake is designed to kick in at around 7-8 knots and then continue to increase its effectiveness as the load increases beyond this speed. The ultimate goal is to maintain helm and choice of direction while keeping the ship's speed below 6 knots. In survival conditions the trick is to prevent taking on board any water and keeping the vessel as buoyant as possible, which means avoiding breaking crests or becoming bogged down in troughs. This is only achievable if the vessel has headway and helm. In my experience, even in the worst conditions it is far easier to obtain "safe water" running with a sea than jogging into it [with the engine]. And this is where Seabrake comes in.

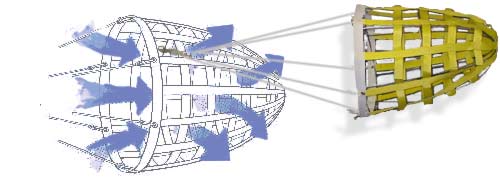

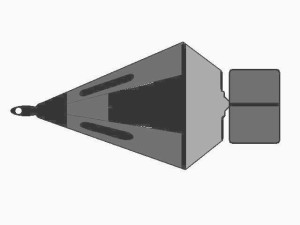

The development of Seabrake evolved from a need to travel in harmony with the sea, with room to maneuver, much the same as rolling along at speed in heavy traffic - as opposed to being out of control and all over the road. Seabrake, in simple terms, is a remote control two-stage speed regulator, activated by a compression spring that opens and closes the drogue's baffle gates. With the baffles closed the flow of water around Seabrake is laminar, exerting just enough drag to improve steering control below hull speed or safe maximum speed. Any sudden acceleration or surfing brought on by a wave crest will cause Seabrake's nose cone to extend, which triggers the compression spring and opens the baffles inward. With the baffles open the flow of water around Seabrake becomes turbulent, instantly increasing its drag by about 70%. Conversely, a sudden deceleration in boat speed (in a wave trough) will release the spring, which will close the baffles, instantly reducing drag and preventing a "stall."

By running before the seas under restraint of a two-stage system of speed suppression and compensation, a vessel may be steered through the worst conditions in relative safety. Reading the immediate wave astern and maneuvering to expose the least amount of stern - quartering the seas rather than taking them on square - is all that needs to be done in order to avoid both the PUSH and the FALL as a dangerous wave passes under the boat. The Seabrake principle has now been in effect for some 15 years and has been tested and evaluated both academically and in the field. It has saved many lives and vessels under horrific conditions, doing so without any technical knowledge or formal training on the part of the users - the "set it and forget it" principle truly applies here.

As a final comment I need only repeat my earlier statement, "speed kills." While running before heavy seas it is important to try to keep the speed range below 6-7 knots, but above 3 knots. Slowing down below 3 knots will result in loss of steerage and allow a vessel to wallow, which is equally unsafe. I base the above on personal experience, but note that individual applications may be subject to a great many variations. Following these guidelines, however, will assist in measuring the general situation.

NOTE: A rival Australian company, Broachbrake International Pty., Ltd., was manufacturing a similar plastic drogue called the Sea Squid for a while. John Abernethy brought suit against the company for infringement of certain legal rights. Broachbrake was subsequently issued a court order to cease and desist and has since stopped making the device. Abernethy told Shane that Sea Squid was an altogether inferior imitation of his product. There is an illustration of the now outlawed Sea Squid in file D/M-12 of this publication.