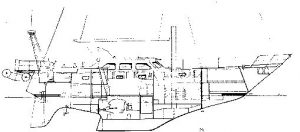

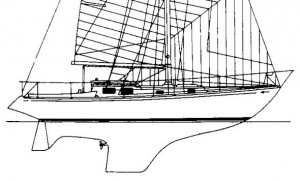

Monohull, Ian Anderson SeaStream 43 MKIII Cutter

43' (13m) x 18 Tons, Fin Keel

Jordan Series Drogue

Force 9+ Conditions

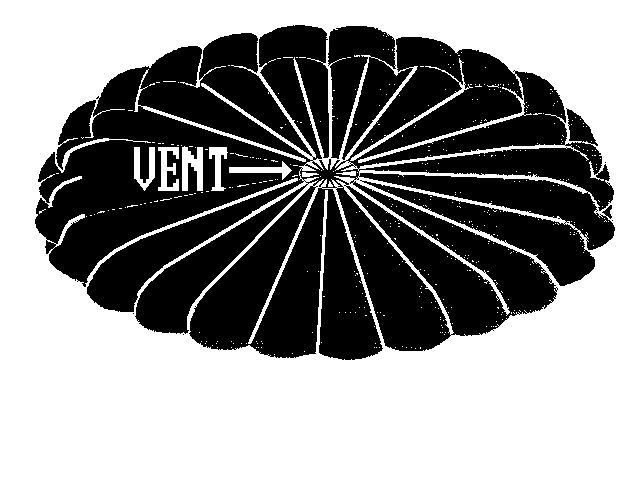

File D/M-21, obtained from Tim Good, UK- Vessel name Shadowfax, hailing port Falmouth, monohull cutter designed by Ian Anderson and built by Seastream, LOA 43' x LWL 36' x Beam 13' 9" x Draft 6' 6" x 18 Tons - Fin keel - Drogue: Jordan Series Drogue on 360' (110m) x 7/8" (22mm) nylon double braid rode plus 14kg chain - Deployed in deep water just south of Madeira while singlehanded midway on passage upwind from Canary Islands to Azores in winds of 45+ knots and breaking seas of 16 - 23 ft. (5 -7m) - Speed was reduced to about 1.5 knots during 36 hours of deployment. Total drift was about 42 nm. Yacht was pooped by a large breaking wave once.

Tim Good has over 20,000 miles of experience, mostly in the East Atlantic and North Sea, but this was his first singlehanded passage. After his mainsail was split by the wind, and then his engine died owing to a fuel pump fault, Tim was unable to heave-to, and so chose to deploy the drogue to minimise his downwind drift:

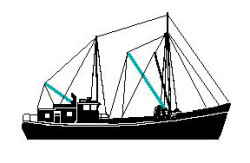

I was sailing singlehanded upwind to the Azores from Gran Canaria. I knew that a strong blow was forecast to arrive as I passed Madeira. I decided to continue on rather than stop in the shelter of Madeira. The blow was stronger than forecast and around dusk I decided to reduce sail and heave-to when the wind had picked up to 45 kts sustained. While reducing sail, my mailsail split down the middle, making it impossible to heave to. I tried to make headway with staysail and engine at around 45 degrees to the sea. Breaking waves were knocking the bow off but the engine kept correcting. Around 1am the engine stopped due to a leaking lift pump and I had no option but to turn and run with the sea and wind. I decided then to deploy the JSD which was in a 100L drybag in the cockpit and the bridles already rigged. I had around 14kg of chain on the end and I threw this over the stern. The JSD then deployed out of the bag smoothly with no chaffe or handling. The boat slowed to around 1.5-2kts. The waves were strangely large and frequently breaking for the windspeed. They'd had a long fetch to gather size from NW Spain. Presumably as a result from the acceleration around Madeira it increased their size. Difficult to say the size. Perhaps 5-7m? About 45 mins after being on the drogue a big wave pooped over the stern filling the very large cockpit. I got pooped a few times but nothing as large as that. I had no issues with chaffe since I have large overhanging chainplates which prevent any chaffe and strong crosby shackles, rated with a breaking strength in excess of half the displacement of the boat. After approx 36 hours I retrieved it single-handed in around 1.5hours. It was easier than I had anticipated as the leader would go around my main winch and with each wave, the leader would slacken sufficiently to winch in a meter or so. I continued on to the Azores and had the mainsail repaired. I made a video of the account here which includes info about the deployment, chainplates and bridle setup.

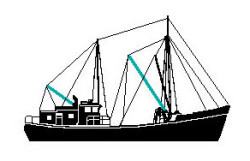

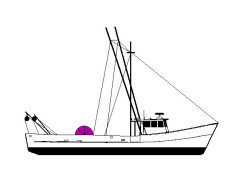

My chainplate design can be seen here:

https://www.chasing-contours.com/series-drogue/

Tim's video is highly informative and demonstrates how well he had prepared his boat in advance of any extreme conditions. Like all of us he had hoped never to need to use the equipment he installed but, as we can see here, his preparations resulted in easy and stress-free management of the conditions. In fact, this is probably the best prepared boat of all our drogue reports, and the result of that is clear to see. His solution for preventing chafe is excellent. Yes, it was probably quite expensive to build and install, but completely eliminates the problem.

Had he not been so well prepared his experience would have been way more challenging. Once again the need for propert preparation is made.

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!