D/C-7

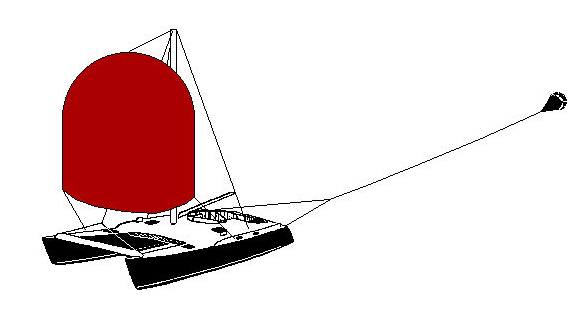

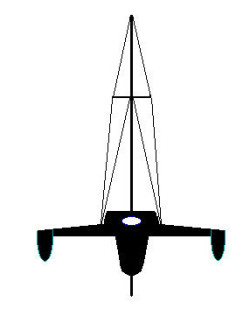

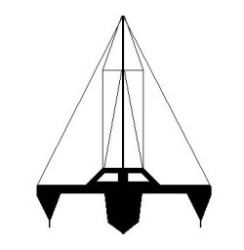

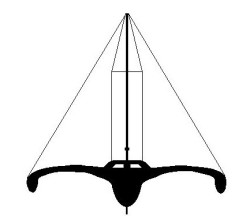

Catamaran, Shuttleworth

34' x 18' x 2 Tons

Sea Squid Drogue

Force 8 Conditions

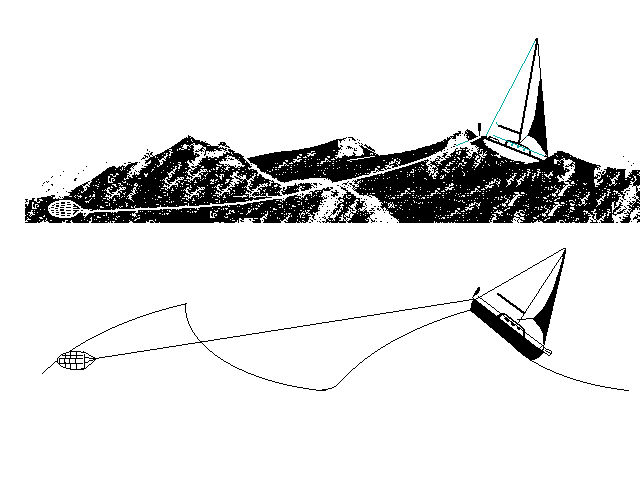

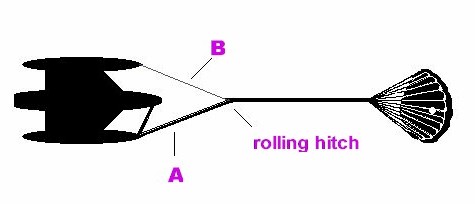

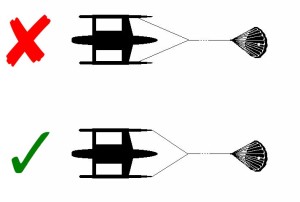

File D/C-7, obtained from Mark J. Orr, Leigh On Sea, UK. - Vessel name Shockwave, hailing port Southampton, ocean racing catamaran designed by John Shuttleworth, LOA 34' x Beam 18' x Draft 18" x 2 Tons - Drogue: Sea Squid on 200' x 7/16" nylon three strand tether, with bridle arms of 30' each and 1/2" galvanized swivel - Deployed while racing, in a low system in deep water about 100 miles west of Cape Finisterre (Spain) with winds of 35 knots and seas of 10-15 ft. - Vessel's stern yawed 20° - Speed was reduced to about 10-12 knots with double-reefed main and half-furled Genoa.

Transoceanic racing skipper Mark J. Orr is affiliated with Prout Catamarans and has participated in numerous multihull races. In the 1995 Azores and Back Race he used an Australian Sea Squid drogue to maintain speed and stability. This feat can be accomplished with high speed plastic drogues like the discontinued Sea Squid or some of Seabrake's solid units - the MK I or the HSD 300. In high winds the forward pull of relatively large sails is opposed by the rearward pull of the drogue and the yacht in between is then able to move at relatively high speeds as though on railroad tracks - if the drogue doesn't fly out of the wave faces. Transcript:

Fortunately it was not our para-anchor that we had to use, but our Sea Squid drogue, which worked brilliantly. Whilst racing from Falmouth to San Miguel, Azores, in the Azores and Back Race, we had a fantastic multihull sail on the way down. After a strong beat at the start, the wind steadily came round to a reach, and then a broad reach whilst steadily building. Late on day two we were sailing with the wind angle at 110° from the starboard bow in a brisk F6-7. The seas were building and the boat was enjoying some marvelous surfing with speeds steadily in the 15-18 knot range. As the spinnaker was doused for full genoa and the mainsail reefed, the roller furling became jammed with half the genoa furled. The mainsail with 2 reefs was fine. As the surfs became longer and faster there was the occasional danger of the bow digging in too much.

Having decided that we wanted to press onto the Azores as quickly as possible, we did not want to reduce too much sail. At the same time we wanted to keep the stern down in the water and prevent the bows digging in. The drogue seemed the ideal answer. We deployed in on two 35' bridles and 200 ft. of 10mm three strand nylon. Once deployed the boat continued under 2 reefs in the mainsail and half furled genoa at 10-12 knots for the next 8 hours. Not once did the bows seriously dig in, and the stern seemed glued to the water. We hand-steered to get round waves that might slow us down, but on reflection could have used the autopilot and rested. It was amazing how secure the boat felt with the drogue out. As the boat accelerated too quickly (on a surf) there was a gentle dampening pull on the stern from the drogue that kept the acceleration gradual and within control. Lessons learned were that the bridles could have been longer, and I would have preferred a stainless steel swivel between the bridle and the tether. We had rigged up for the para-anchor off the bow and used its bridle for the drogue, which was fun to de-rig. However for the leg from the Azores back to Falmouth we rigged bridles from bow and stern so that we only had to attach the tether and the appropriated drag device. We will do this in future passages as it will speed deployment and save energy. It was the first time we had used the drogue on this boat and it was brilliant. If we had not had the drogue we would have had to slow right down. Having it on board meant that we could maintain a good racing performance in apparent safety.

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!