Gauntlet, Bermudan Sloop

42' x 14 Tons, Full Keel

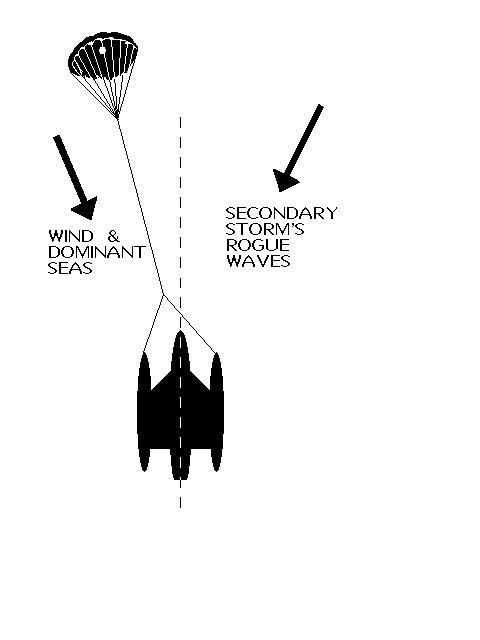

18-Ft. Dia. Sea Anchor

Force 8 Conditions

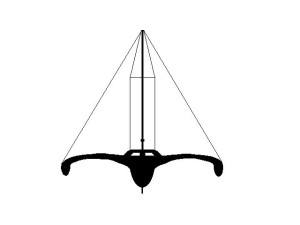

File S/M-31, obtained from R. Walton, North Gosforth, UK. - Vessel name Lady Emma Hamilton, hailing port Amble - Gauntlet, Bermudan Sloop, LOA 42' x LWL 33' x Beam 9' 6" x Draft 6' x 14 Tons - Full keel - Sea anchor: 18-ft. Diameter Para-Tech on 400' x 3/4" nylon braid rode with 5/8" stainless steel swivel - Partial trip line - Deployed in a gale in shallow water (45 fathoms) in the North Sea, about 125 miles east of Aberdeen, Scotland, with winds of 40-45 knots and seas of 28 feet - Vessel's bow yawed 20° at the peak of the gale in Force 8, increasing to 45° when the wind moderated to Force 6 - Drift was 7 n.m. upwind during 23 hours at sea anchor.

This file was forwarded to Victor Shane by Mike Seal, proprietor of Cruising Home Ltd. in the United Kingdom, to whom we are indebted.

Lady Emma Hamilton is a double-ended Bermudan Sloop, similar to Bernard Moitessier's Joshua, hailing from the Northumberland harbor of Amble (about 40 miles south of the Scottish border).

In June of '97 her owner, R. Walton, was sailing her back to Amble from Bergen, Norway, when she ran into a gale in the infamous North Sea, about 125 miles offshore, east of Aberdeen, Scotland. Walton describes the sea states as "cycloidal, steep, breaking/unstable" on the form he filled out, which is believable, given that the yacht was in only 45 fathoms of water, and that the northerly wind was blowing contrary to a northwesterly current. The average waves were about 28 feet high at the time, as measured by the crew on a nearby oil rig. Transcript:

Rode led over bow roller and tied to it. Rags were used to wrap around rode at bow fitting to stop chafe. In future I will use a leather "tube." Checked for chafe every two hours - rags wore through, but rode only very slightly scuffed. No bridle used. Once wind moderated the yaw increased, but at the peak of wind boat held almost dead into wind. We hove-to just next to an oil platform, "SANTAFE 135," which relayed a message to our destination advising our delay, etc.

Hove-to at 0600 hrs. Wind moderated by 2300 hrs, but waited till first light to haul in the anchor as this was the first time I had ever used it. Made way at 0500 hrs 28 June in Force 6 still from North. Initially our drift was imperceptible (no noticeable slide or turbulence at all! Just stayed put). But by dawn it was obvious we had drifted upwind past the oil rig, so current was overcoming drift downwind.

Throughout, the tension on the rode seemed very great. Considerable windage from 60 foot mast and [roller] furled genoa. No sail or other windage hoisted at stern. Boat motion was quite extreme, with gunnel to gunnel roll being set up, then dying down again every few minutes.

The Para-Tech sea anchor and Delta Rode were supplied by Cruising Home Ltd. UK as a complete package, with deployment bags for both (rode in Rode Bag) - they worked perfectly. I just undid the straps and the Rode Bag toggles and tossed it overboard - it all sorted itself out and within five minutes we were riding head to wind. I am totally sold on the concept! We had been pooped twice before we hove-to and the seas increased in ferocity somewhat later.