S/M-12

S/M-12

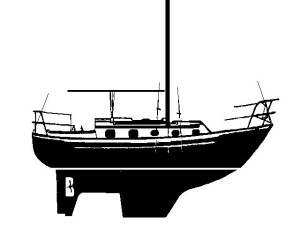

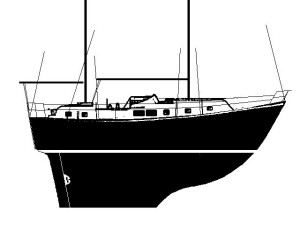

Carter 33 Sloop

32' 7" x 4.5 Tons, Fin Keel

12-Ft. Dia. Sea Anchor

Force 8-9 Conditions

File S/M-12, obtained from Steven Callahan, Ellsworth, Maine - Vessel name Karpouzi, hailing port Lamoine, sloop, designed by Dick Carter, LOA 32' 7" x LWL 25' x Beam 11' x Draft 5' 6" x 4.5 Tons - Fin keel - Sea anchor: 12-ft. diameter Para-Tech on 250' x 5/8" nylon three strand with 1/2" galvanized swivel - No trip line - Deployed during a gale in deep water north of Bermuda, with winds of 35-45 knots and seas of 8-12 ft. - Vessel's bow yawed 30° off to each side with two opposing sets of waves approaching from dead ahead and dead astern - Drift was estimated to be 3.25 miles during 4 hours at sea anchor.

Steven Callahan is well-known for his best seller, Adrift. The book is a journal of the seventy-six days that he spent drifting in a life raft after his 21-ft. sloop Napoleon Solo hit an unidentified object and sank in the middle of the Atlantic on 4 February 1981. He journeyed to the limits of human despair in those seventy-six days, yet in the end cheated death and emerged a survivor. Adrift (1986, Houghton Mifflin Co.) won the Salon du Libre Maritime award and has been translated into twelve languages.

Callahan has been involved in many areas of the marine industry since 1968. He has logged tens of thousands of blue water miles, including one single-handed and three double-handed Atlantic crossings. A former contributing editor to SAIL and to SAILOR, he wa at the time of this writing associate editor of Cruising World.

Victor Shane delivered a 12-ft. diameter Para-Tech sea anchor to Callahan in 1989, for use and evaluation on board his boat Karpouzi, a fin-keeled Carter 33 sloop. The para-anchor was used a year later, in a Force 8 gale north of Bermuda. Here is a transcript of Callahan's feedback

On 28 May, 1990, Karpouzi and her three merry crew were completing a delightful week of sailing from St. Martin, and approaching Bermuda. We planned to bypass the island and continue directly to Maine. Our weather, however, was deteriorating, and the forecast was for a day or so of rain and winds of 20 knots.

By midnight the barometer began to fall more rapidly - about .05 inches per hour, and we were broad reaching fast under double-reefed main and working jib. We could hear Bermuda Harbor Radio, about 30 miles east of us. Harbor radio was busy with incoming traffic problems and reports of a developing low that no one had paid much attention to. Through the night they logged winds to 42 knots and predicted seas to 25 feet.

As we proceeded north, the wind strengthened and backed slightly so that we ran dead before waves that I estimate to have been 10-15 feet. All was under control. The barometer began to rise by 06:00 on 29 May and the wind lightened slightly for about a half hour, but then the wind came up hard again and continued to back. In a very short time we were hit with heavy head winds and significantly rising seas from dead ahead, while we continued to surf down 10 foot waves from dead astern.

In 50,000 miles of offshore sailing I have often dealt with heavy seas from a variety of directions, but that was the first time that significant waves approached each other from precisely opposite direction. This, of course, set up a dreadful sea state. When crests coincided, the peaks jumped skyward and the wave slopes were very steep. (Note, in the attached DDDB form, wave height, period, and length are very approximate values because they were all extremely variable due to 180° wave collisions - a bit like being in a blender). I estimated wave height by standing on the cabin top - my eye level about 10 feet above water.

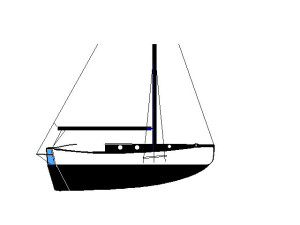

Karpouzi's beam is 11 feet, or the average size of the breaking waves, so I declined Neptune's invitation to get rolled by laying broadside to the waves. We could not carry much sail in the wind, and in any case, heaving-to or beating would put the boat too far off of the approaching waves, increasing the danger of being stalled, pushed back, and rolled. The only feasible solution was to put out the sea anchor. We decided to set the sea anchor just as we would a regular anchor.... We keep the anchor in its own locker in the head of the V-berth, with the rode flaked under it. This allows us to run the rode straight aft, out of the cabin, and forward over the anchor roller.... As I dunked the anchor over, we threw the engine in neutral and drifted back. The parachute opened perfectly and within thirty feet it began pulling, allowing us to pay out line and adjust things just right. A few waves towered above me and one slammed over the foredeck just irritatingly above boot level.

We payed out about 250 feet of the rode and adjusted the length every 30 minutes to avoid chafe. This length proved enough; the sea anchor sometimes neared the surface so we could see it and it rode about a wave trough away from us. I chose not to use a tripping line to avoid any possible foul up, but we tied a huge Norfloat ball to the float line, which we could easily see from far away.

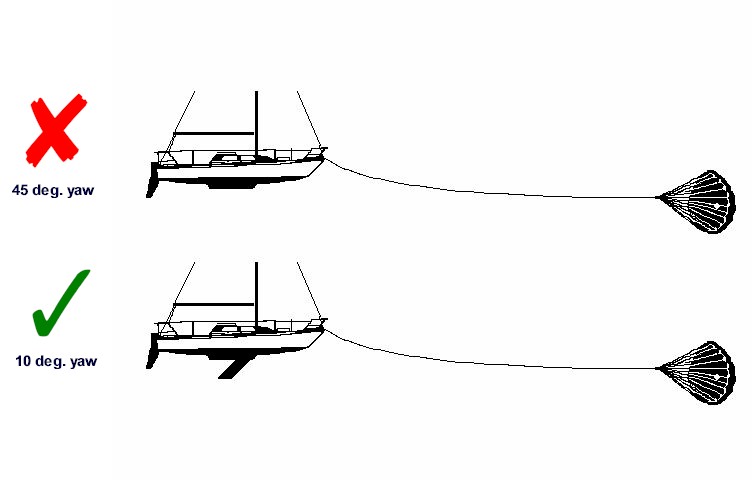

The boat did sway from side to side, creating huge side loads on the anchor roller cheeks, so be advised to use either very sturdy chocks or heavy roller. Ours was a heavy duty universal roller that is advertised for boats to 54 feet, but I believe the side loads on a 54 foot boat would have bent the roller in half. As it was, I was a bit worried. To control sway and remove these side loads, next time I will likely set the sea anchor from a regular chock and possibly haul it off to the side with a rolling hitch and secondary rode to lay 20 to 30 degrees from nose onto the waves. Note that the rode jumps up as the bow plunges downward, so whatever chock you use should have a positive lock across the top.

The only real problem we encountered was a very heavy loading on the steering gear. Karpouzi is tiller steered and at first we just tied it off, but as large waves broke on her, she surged aft, stretching the anchor rode until stopped and pulled forward again. The rudder was yanked mightily by the backward motion and the tiller wiggled about like a snake. Our solution was to give the tiller a shock absorber, just as the nylon anchor rode acted as a shock absorber for Karpouzi. We tied half inch shock chord to the tiller, which allowed it to move 20 or 30 degrees without much problem but prevented the rudder from going hard over, where it could shear off its fittings.

After only four hours on the sea anchor, the wind continued to back and lightened, so that finally we were laying broadside to the now calming waves. It was quite uncomfortable and more dangerous than setting sail. With full throttle we were able to easily retrieve the rode as we steamed up to the pickup float, which we noted had enough windage to float to leeward of the anchor most of the time, so we had no worry about tangling the sea anchor lines. It was a simple matter to pick up the float, trip line, and anchor. Within 20 minutes all was stowed away and we were off.

We drifted 3.25 miles in those four hours, which is a bit more than I expected, but currents around Bermuda are very uncertain. Further tests will compare Karpouzi's normal drift rate with her drift with the sea anchor set. I will certainly be more eager to set the sea anchor in marginal conditions in the future.

It is disappointing to note that Karpouzi's bow was yawing 30° off to each side (i.e., through a total arc of 60°). By all tokens the sea anchor was big enough to have done a better job.

Victor Shane suspects that the conflicting waves - approaching from ahead and astern - might have had something to do with this. Certainly the angle of yaw will have a great deal to do with the amount of slack that finds its way into the system as well. Much of this slack can be a result of orbital rotation causing convergence between boat and sea anchor. Essentially the wind pushes the boat away from the sea anchor, keeping the system taut. Orbital convergence, however, can move the boat and sea anchor toward one another, introducing slack into the rode, sometimes by an amount equal to twice the wave height (twenty feet of slack rode in ten foot seas, for example). Callahan reports significant waves approaching each other "from ahead and astern." Here, not only do we have the rotation associated with the waves approaching from ahead, but also, possibly, the rotation associated with waves approaching from astern, as evidenced by the heavy loads on the rudder, mentioned. This combination could have the effect quadrupling the amount of slack - and attendant yaw - when the crests of the secondary waves coincide with the troughs of the approaching waves.

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!