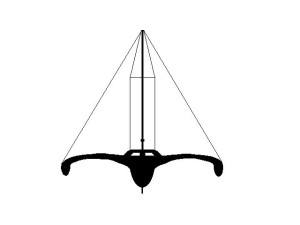

Trimaran, Newick

40' x 28' x 3 Tons

36" Dia. Galerider

Force 8-9 Condition

File D/T-10, obtained from Deborah Druan, Farmingham, MA. - Vessel name Greenwich Propane, hailing port Greenwich, CT, ocean racing trimaran designed by Richard Newick, LOA 40' x Beam 28' x Draft 5' 6" (2' 6" board up) x 3 Tons - Drogue: 36" Diameter Galerider on 250' x 5/8" nylon braid rode - No bridle - 5/8" Stainless steel swivel - Deployed in a gale in deep water about 400 miles NE of the Azores with winds of 40-45 knots and seas of 18 ft. - Vessel's stern yawed 10° - Speed was reduced to about 3 knots during 10 hours of deployment.

Debbie Druan is the United States' foremost female multihull skipper - America's Florence Arthaud. She has won numerous first-to-finish trophies to date, the latest on her Formula 40 racing trimaran, Toshiba. Doubtless she will make it to the Whitbread. Debbie is also commodore of the New England Multihull Association and has written numerous articles about ocean crossing and heavy weather tactics in the journal of the NEMA. In May 1994 she arrived in Bermuda with David Koshiol and Joe Colpit to deliver the 40-ft. Newick trimaran, Greenwich Propane, to Plymouth, England. The owner of the boat, John Barry, was to race it in the 1994 Two Star Double Handed Transatlantic Race from Plymouth to Newport. On the Horta to Plymouth leg of the crossing Debbie and crew ran into a gale. The following is a transcript of her report, appearing in the September 1994 journal of the NEMA (reproduced by permission):

The gale hit us on May 23. We were 838 n.m SW of England and 424 n.m. NE of the Azores. It was good to know about the low in advance because by noon when it started building rapidly we knew why. We went from the full main, jib, and spinnaker to just the jib, surfing at 10-12 knots down 8 ft. seas in 18-22 knots of wind. We decided to just take the main down and not deal with reefing. We weren't racing and just needed to get the boat to England in one piece and on time, so we played it conservative. By 5:00 PM as the wind and waves increased we just kept rolling in more and more jib and took the rotation out of the mast. We were still going just as fast. It was tiresome, wet and cold on watch, so we went to a 2 hours on and 4 off system. Late that night it had moderated down to 30 knots and 12 ft. waves, so we started thinking the worst was over.

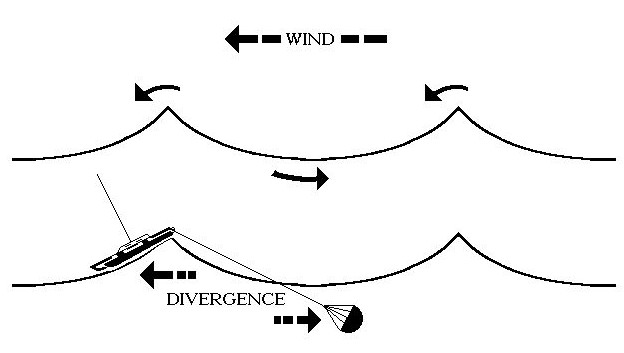

The next morning we started getting hit by rain squalls and an increase to 40 knots and 18 ft waves. There wasn't much jib left out so we started wondering what we were going to do when we ran out of jib. The problem was that the boat didn't have a barometer and we had no way of telling if we were moving along with this storm, or if it was intensifying. After much discussion between the pros and cons of setting the para-anchor or the Galerider, we decided on the Galerider because it seemed out of the question to turn the boat up broadside to the 18-20 ft steep seas to set the anchor off the bow. So we pulled out the Galerider and got it ready just in case. It wasn't the high wind that concerned us but the fact that the boat just was not steering down the steep waves very well. Occasionally she would surf madly down the face of a wave, the rudder would cavitate, we'd lose control and go down a wave sideways. You only needed for this to happen once and the boat could trip over itself. As Joe had once capsized in another trimaran, he was familiar with the warning signs.

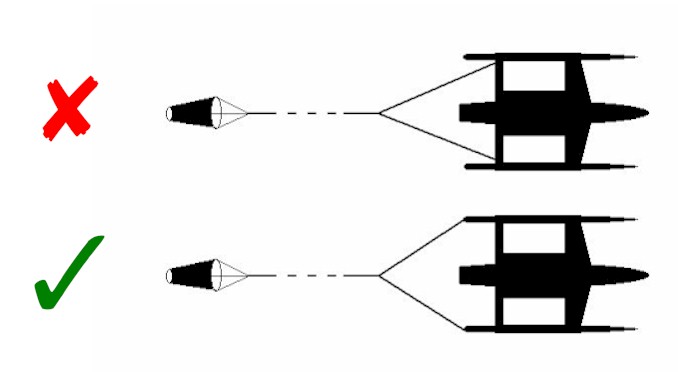

Finally, after 24 hours of hand steering down these steep seas David, who was on watch, yelled down to us "hey these suckers are getting bigger, we better do something." As another large wave slammed us sideways, you could hear the nervousness in his voice. They were over 20 ft now. We determined that we must be moving along with this system, as the wind was supposed to change direction after it had passed, and it hadn't. We needed to stop and let it pass by us. We were all worried. None of us had ever set out a drogue before. The Galerider was constructed of thick 2" webbing in a criss-cross pattern with a 3 ft diameter opening. Attached was 6 ft of 3/8 chain and a 5/8 swivel. The line was 250 ft. of 5/8" nylon braid. The blocks on the ama sterns weren't strong enough to be used for a bridle, so we used the main stern anchor cleat to secure it.

While David steered, I made sure all the line was flaked and ready to pay out of the bag in the cockpit, and Joe stood on the main transom with the drogue. He looked like he was standing over the edge of a huge cliff with 20 ft deep troughs and 250 ft to the next wave crests. Joe took a wrap around the cleat and gently dropped the Galerider off the stern: instantaneously the Galerider took hold and you felt the boat take a huge tug backward. The transom was pooped instantly as a wave overtook us. Joe paid out 150 ft of line. We waited, wondering if the anchor cleat was holding. You could see the Galerider riding the crests of the waves, so he paid out another 100 ft of line to take the strain off the cleat. Now you could see only the line riding in the waves. Soon we were surrounded by mountains of waves and they just came up, passed under the boat, and away. We were calmly and slowly going down wind at three knots.

Our first reaction was "why hadn't we put it out sooner?" Even without a bridle, the Galerider stayed centered off the stern. It only yawed back and forth a little. It was now easier to steer. For anti chafe gear we used a rag on the cleat and kept and eye on it. Ten hours later the wind and seas had moderated enough and we simply pulled the drogue back in. Joe from the stern pulled it in hand over hand, waiting for the line to go slack between waves. David tailed the end of the line on the runner winch into the cockpit.

Two days from the onset of this low we were able to put the full main back up. For the next 800 n.m. to Plymouth we'd have 2-3 days of wet, bumpy and cold conditions to one day of dry and warm.... The last 300 n.m. was a beat to weather. As we were worried about the rig we sailed the boat as conservatively as possible. We made our approach to England by the Lizards.

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!