D/T-4

Trimaran, Newick

31' x 26' x 1.5 Tons

4-Ft. Dia. Conical Drogue

Force 9-10 Conditions

File D/T-4, obtained from B.J. Watkins, Arnold, MD. - Vessel name Heart, hailing port Richmond VA, Val ocean racing trimaran designed by Richard Newick, LOA 31' x Beam 26' x Draft 5' (2' 5" board up) x 1.5 Tons - Drogue: 4-Ft. Diameter cone (unknown make) on 200' x 1/2" nylon braid tether, with bridle arms of 75' each and 1/2" galvanized swivel - Deployed in a whole gale in deep water about 300 miles NE of Bermuda with winds of 40-50 knots and seas of 20 ft. - Vessel's stern yawed excessively - Damage and risk of capsize lead to the abandonment of the boat.

B.J. Watkins was singlehandedly sailing Heart from Annapolis to England to participate in the 1988 C-STAR (Carlsberg Singlehanded Trans Atlantic Race). Her intent was to become the first American woman ever to finish that race. "That is not what happened, unfortunately," writes B.J. in an article entitled The Agony of a Premature Defeat (March/April '88 issue of Multihulls Magazine).

B.J. departed Annapolis on 9 April 1988. On the third or fourth day out the boat hit something, damaging the rudder. A week later, 380 miles NE of Bermuda, Heart ran into a whole gale. B.J. set a 4-ft. diameter, conical drogue - unknown make - off the stern.

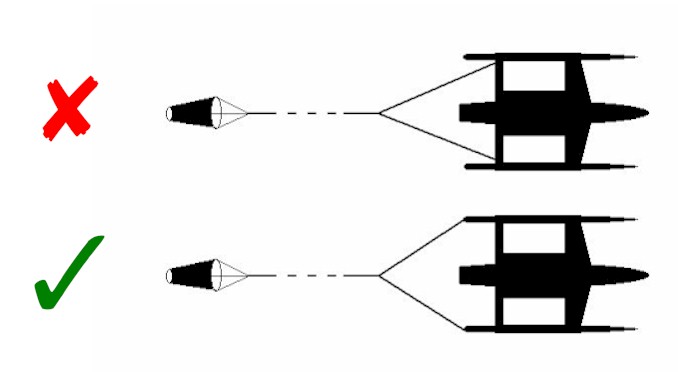

While the cone was too small to pull the bows into the seas (B.J. had tried that once and the boat just laid beam-to), by all tokens it should have done a good job of pulling the stern into the seas. But it did not. Why not? Likely because of the incorrect attachments points of the bridle. Heart was practically identical to Galliard (file D/T-2), both trimarans being Newick Val 31s. The difference was that Tom Follett deployed a 5-ft. diameter Shewmon with a bridle leading to the extreme outboard ends of the floats, whereas B.J. deployed a 4-ft. cone with a bridle secured to chain plates located on the cross-arms, inboard and forward.

The cone may have been on the wrong part of the wave train as well. In order to keep the stern aligned into the full blown gale B.J. found that she had actively to steer the Val trimaran. The pull of the drogue was not constant. Now and then the yacht would surf down the face of the steeper waves. To steer risked further damage to the rudder. To not steer risked a broach and possible capsize. The barometer kept falling. Components began failing. The seas built up and finally started to break over the small trimaran.

The situation became untenable and B.J. had no alternative but to turn on the EPIRB (Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon). She was taken off the crippled trimaran by the Dutch container ship Charlotte Lykes.

B.J. Watkins had spend about $50,000 in preparing her boat, which was uninsured once it was 200 miles from the U.S. coast - a bitter loss. A transcript of the DDDB feedback submitted by B.J. Watkins follows. It includes portions of related correspondence with Donald Jordan (by permission):

I have enclosed a copy of the correspondence I had with Donald Jordan. I hope this is helpful. Mr. Jordan and I have reached the conclusion that the reason the sea anchor did not pull the stern to the seas was because of the location of the attachment points. We feel that they were too far forward on the boat and too far inboard....

[From the Jordan correspondence]: I cannot tell you exactly what size drogue I had. It was a cone shape, approximately 4 feet in diameter at the widest point. It was original equipment which came with Heart, so I do not know the exact measurements. I had attached snatch blocks to half-inch "D" shackles whose pins formed the pins for the turnbuckles on the mast rig. The bridle lines ran through the snatch blocks to the primary winches. I am at a loss to explain why the boat did not ride stern to the wind. My experience with Heart prior to rigging with the wing mast was interesting. I had on a previous occasion deployed the sea anchor from the bow of the main hull, no bridle. This was done in Long Island Sound, 50-knot winds, 5-8 foot seas, no bridle. Heart laid beam to the seas at that time. We had the board up but the rudder was in place. Dick Newick suggested that possibly if we had raised the rudder we might have then set bow-to. The action of the sea anchor at that time prompted me to investigate further. We added the bridle and decided to try stern-to.... I agree that the best arrangement is to attach the bridle to special reinforced fitting provided at the aft ends of the amas.

UPDATE: Two years later B.J. Watkins and her teammate Boots Parker were participants in the 1990 Two Handed Transatlantic Race on the 45-ft. Peter Spronk catamaran Skyjack. On their way to England they lost both rudders (the shafts had been fabricated out of aluminum instead of stainless steel). And, while attempting to limp to the Azores on one spare rudder they ran into two Force 8 gales!

However, this time B.J. had an 18-ft. diameter Para-Tech sea anchor on board. In the second gale she deployed it. The orange parachute pulled the bows of Skyjack into the teeth of the gale, parking the boat and minimizing damage.

In a subsequent telephone conversation with Victor Shane, B.J. said that the parachute sea anchor performed in a most satisfactory way - it was a morale booster and it allowed them to "call time out" in a difficult situation.