Kindred Spirit III was newly purchased by her owners, who had spent the previous two months planning the delivery and preparing themselves and the boat for the trip. The preparations included the purchase of a parachute-type sea anchor system consisting of a 24' diameter Para-Tech model; 600' of 3/4" braided nylon rode made up in two 300' shots so that the rode was of manageable weight, each shot having heavy duty thimbles (one with thimbles at both ends, and one with a thimble at only one end); a 3/4" stainless swivel for connecting the rode to the anchor shackle; and a 7/8" galvanized shackle for connecting the two shots of rode to each another. Additionally, the owners installed heavy duty hawse holes in the forward bulwarks approximately three feet aft of the stem. These were specifically intended as the lead for the sea anchor rode, and were deemed necessary because Kindred Spirit III's bow chocks were open top chocks and were located atop a 6-inch bulwark, resulting in an unfair lead to the bow cleats seated on deck. The presence of twin steel anchor roller and a large deck-mounted winch made a chafe-free lead directly over the bow problematic.

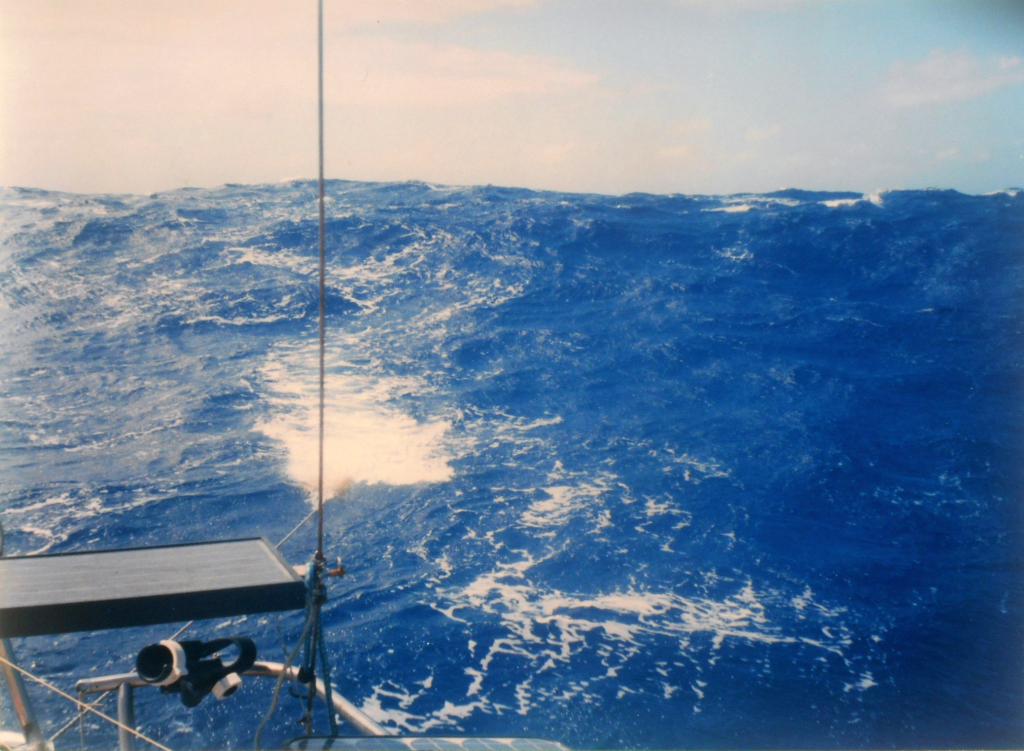

Six days out of St. Croix Kindred Spirit encountered a line squall which destroyed the leach of her 135% roller furling Kevlar tape drive genoa, rendering it useless and unrepairable with the materials and equipment on board. Proceeding under staysail, reefed main and mizzen, Kindred Spirit was faced with backing wind, and in late afternoon of 2 November was motorsailing into building wind and seas under staysail and mizzen only. Although the boat was moving comfortably and under full control, at 2000 the skipper decided to heave-to because the wind continued to be unfavorable, the seas were continuing to build, and he was concerned that the crew not become fatigued.

Hove-to with staysail and unreefed mizzen, Kindred Spirit rode out the night in comfort, and the skipper enjoyed a full night's sleep. At 0600 on 3 November the skipper decided to deploy the sea anchor because both wind and seas had continued to build during the night and, while the vessel continued to ride comfortably hove-to, the failure of the genoa caused the skipper to have concerns that the other heretofore undetected gear weakness could result in damage to the staysail, the mizzen, or the running rigging, any one of which could produce a dangerous situation.

Additionally, the barometer was reading 1020 and above, indicating that what was being experienced was not a passing low pressure front or cell, and thus no reasonable estimation could be made of the current situation's expected duration. (It was later determined that what was experienced was probably a strong local enhancement of the NE trades, occasioned by a deep low pressure trough which had fallen off the US southeast coast the previous day, creating tightly-spaced isobars between it and the high pressure ridge around whose backside Kindred Spirit's route was planned).

The sea anchor, rode and related hardware, all stowed in the V-berth forward, were brought to the center cockpit and assembled. Both the movement of the equipment and its assembly were difficult due both to weight (even at 300', the rodes weighed in with thimbles at almost 70 lbs. each) and to the motion of the boat as it rode 20+ foot waves. This process, which required managing 600' of 3/4" line in the center cockpit in a manner which permitted access to both ends of each of the 300' shots without creating any tangles, was slow, tedious work which took almost two hours to complete. In the skipper's opinion, attempting to accomplish this task hurriedly in an emergency situation is a recipe for disaster, and attempting it on an open foredeck in any kind of severe weather is unwise.

Once fully assembled and checked, including double mousing of the shackles, the bitter end of the rode was led forward outside all rigging and lifelines and was inserted through the hawse hole from the outside in and about 150' of rode was pulled through the hawse hole and made neat and fast on the foredeck. This rather awkward process was required because the heavy duty thimbles on the 3/4" line would not fit through the hawse holes, even though the hawse pipes installed were the largest available from boating catalogues. A six foot length of fire hose was slipped over the rode's bitter end using a boat hook as a needle, and was then run down the rode to the hawse hole, where it was made fast to the bow cleat. This was accomplished by cutting a "V" shaped notch in one edge of the flat fire hose, and then running a short piece of 3/8" line with a stopper knot through the hole and tying the fire hose to a cleat [so it could not migrate]. This was the only trip to the foredeck required during the entire deployment operation. A 20" round fender buoy to serve both as a locator and as a trip line float was attached to the short nylon web tether provided with the sea anchor. No other trip line was used.

The sea anchor was then deployed from the relatively protected amidships weather deck adjacent to the center cockpit with the boat still hove-to. During deployment, the rode was snubbed about every 50' both to encourage the anchor to emerge from the storage/deployment bag and to help assure that the rode was running free. The boat did not respond to the sea anchor until almost all the rode was deployed and some substantial load was on the rode, at which point she came smartly round to windward and lay about 20° off the wind. The staysail was then doused and secured before it could drive the bow further off the wind and broadside to the waves.

The unreefed mizzen, of approx. 195 sq. ft., was left up as a riding sail the entire time at sea anchor, the intent being to get the boat to lie 40+ degrees off the wind in an attitude similar to that achieved when hove-to. While this did stabilize her motion somewhat, the sheeting angle needed to bring the bow down the desired amount was, in the skipper's opinion, such that too great risk of sail damage existed, so closer sheeting resulted in a stable wind angle of about 30 degrees.

Laying relatively quietly to the sea anchor, Kindred Spirit received only spray on her deck for the 18 hours she lay-to, except for one boarding wave which was the second of two very steep and large waves so closely spaced that her bow was unable to rise from the back of the first to ride the face of the second. The sea anchor consistently "pulled" her bow through the face and crests of waves. Although the anchor rode was bar tight, no jerkiness was experienced, and the rode seemed, between stretch and catenary action, to exert a constant pressure on the deck cleat to which it was secured.

The sight of the 20" round red float bobbing happily on the crest of the next wave in the train was a sight reassuring beyond description. On the other hand, the 3/4" rode, so massive in the cockpit, looked every bit like a string, from which it seemed Kindred Spirit was hanging for dear life. On several occasions the skipper was grateful that he had gone up a size from the rode size recommended.

Every two hours or so a foot or two of rode saved on deck for the purpose was released to even out any chafe. No chafe or even black marks from the inside surface of the fire hose was ever noted. Because the load on the rode was very high, the paying out of rode was a testy business. To avoid even the possibility of a runaway rode and possible loss of the sea anchor, an amidships cleat was used as a second securing point, and the rode was secured to this cleat with enough slack to permit both the paying out of the desired foot or two and the reattachment of the rode to the primary bow cleat. While this arrangement was never tested to its fullest, there were small mishaps which proved the value of the double attachment. Serious injury to hands and fingers is a real danger here, and must be taken seriously.

The skipper had intended to utilize a "Pardey bridle" to bring the bow 40-50° off the wind, primarily for comfort. The riding snatch block normally used in this setup was not attached to the rode before the rode was under load due to the risk of mishap during deployment. After deployment, it was discovered that the 6 foot chafing gear extended so far down the rode that it was impossible safely to reach beyond it to attach the snatch block. The load on the rode was so great that the skipper decided to not risk mishap by attempting to bring the rode alongside to permit attachment of the snatch block, and the bridle idea was scrapped. While the boat's motion was not extreme, it was uncomfortable and enervating. The relative comfort of lying hove-to was significantly higher than the motion experienced lying to the sea anchor without the benefit of a twin attachment point scheme. During future deployments a shorter chafing gear rig will be used and the snatch block will be deployed as a high priority.

During the morning of 4 November the wind and sea began to abate, and by noon the sea anchor retrieval process began. The initial retrieval of the rode was relatively straightforward, as Kindred Spirit was slowly motored toward the sea anchor guided by the orange float, which proved invaluable for this purpose. Due to the remaining wind and sea, constant attention was required to assure progress in the direction of the anchor, and prearranged hand signals from the foredeck to the helm were an absolute necessity. As the rode came aboard, the problem of a now wet 600 feet of 3/4" line on the foredeck became serious. As a practical matter, there was nothing to be done during the retrieval process except to assure that the rode was securely on board and not underfoot. As the float came to be retrieved a significant unexpected problem presented itself.

Upon securing the float aboard, attention was given to the retrieval of the sea anchor itself. Buoyed (no pun intended) by the successful sea anchor experience, the foredeck crew failed to anticipate the extreme load still on the nylon web [float line] tether due to the weight of the now deflated but wet 24 foot nylon parachute and to the strong motion of the boat as she bobbed in the sloppy leftover seas. The male crew member got his upper arm tangled in the webbing, and caught between the webbing and the upper lifeline. Before he was able to extract himself the loads badly bruised his upper arm. Had the tether been smaller in diameter, or had the crew member caught a wrist or finger, broken bones would have been distinct possibilities. It is strongly recommended that much greater consumer education emphasis be placed on the loads and resultant potential dangers associated with anchor retrieval. In the skipper's opinion, retrieval is at least as dangerous as deployment and is especially tricky due to the random load cycling resulting from the uneven motion of the boat as the anchor rode and tether become shorter at the late retrieval stage. Visions of plucking a deflated sea anchor from the water while hanging over the bow with a boat hook are not only fantasies for all but the very smallest equipment, but are also downright dangerous because they so grossly misrepresent the actual loads and associated dangers of sea anchor retrieval.

Upon final retrieval, the anchor, rode and miscellaneous hardware was stowed on the large afterdeck. While this exposed the rode to sunlight, no practical alternative was found which did not involve dragging 600 feet of salt water soaked rode through the salon to the forward head. Minimum sea anchor equipage should include a tarp or other device with which the retrieved rode and sea anchor can be securely protected from the sun and still remain on deck. Future enhancements to Kindred Spirit's storm preparations will include two life raft canisters permanently attached to the aft cabin roof, customized with adequate drain holes and thus intended to permit both dry and wet storage of the sea anchor, rode, and miscellaneous hardware. An anticipated benefit of this arrangement is the ability to substantially make up the sea anchor assembly before departure, thus significantly reducing the time required to deploy.

In summary, the parachute type sea anchor performed in a flawless manner during deployment in moderate gale wind and sea conditions. The ride while at sea anchor was uncomfortable but is expected to be substantially enhanced by use of a bridle off the side of the vessel, thus permitting the adjustment of the vessel's attitude to wind and seas. The 24' diameter sea anchor and its 3/4" rode are large, heavy pieces of equipment whose assembly, deployment and retrieval require very detailed planning and a realistic understanding of the conditions on a vessel in circumstances which make such deployment desirable. Finally, the notion that a 24' diameter sea anchor is a practical means of stopping for lunch is just not a realistic expectation. Heave-to for lunch, leave the sea anchor for when conditions make lunch an effort.

This skipper is grateful that his first deployment was in conditions which were relatively forgiving, and I encourage anyone purchasing a sea anchor to fully deploy, lie-to and retrieve it in moderate conditions. The education thus obtained cannot be described. And, don't leave home without one.