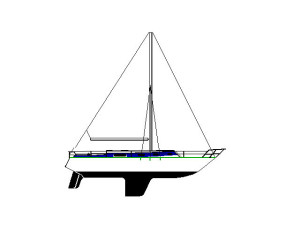

Venture 222 Sloop

22' x 1 Ton, Centerboard Keel

12-Ft. Dia. Sea Anchor

Force 3-4 Conditions

File S/M-11, obtained from Harley L. Sachs, Houghton MI. - Vessel name Gamesmanship, hailing port Houghton, Venture 222 sloop, designed by Roger MacGregor, LOA 22' x LWL 18' 6" x Beam 7' 4" x Draft 4' 6" x 1 Ton - Centerboard swing-keel - Sea anchor: 12-ft. Diameter Para-Tech on 100' x 3/8" dia. nylon three strand rode, with 5/16" stainless steel swivel - No trip line - Deployed during passage of frontal trough in shallow water (7 fathoms) on Lake Superior with wind gusting to 20 knots - Vessel's bow yawed 10° with the swing-keel down and 45° with the swing-keel fully raised.

Way back in June 1988 Victor Shane sent a letter to the editor of Cruising World Magazine, asking for feedback on sea anchors and drogues. Mr. Harley Sachs read the letter and responded with the following feedback:

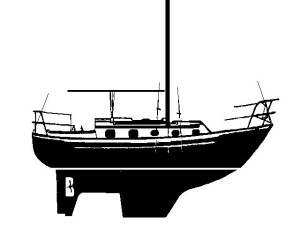

For your database: Vessel, MacGregor Venture 222 sailboat, swing keel, transom hung spade rudder, LOA 22 feet, weight about 2,000 lbs. Conventional wisdom (Chapman and the boating supply catalogs) suggested a 30-inch conical drogue sea anchor. This does not work with my boat.

My wife and I decided to test this equipment on a breezy day with four-five foot waves on Lake Superior. I launched the 30-inch cone from the bow on about fifty feet of line and lowered all sail. The boat assumed a position with the seas abeam and would not face into the waves no matter what the rudder position was. With the sea anchor shifted to the stern, the result was the same. The motion of the boat was violent and I could hardly move about on deck.

I hoisted a small riding sail on the back stay. This had an immediate, remarkable damping effect on the boat's motion but did not cure the beam-on attitude of the boat to the seas. The 30-inch conical drogue was pronounced a failure.

Sachs turned out to be a multi-faceted sailor who was, among other things, writing a book on nautical humor (Irma Quarterdeck Reports, Wescott Cove Publishing, 1990). Shane mentioned the similarity between his disappointing experience with the small cone and those documented by Adlard Coles in Heavy Weather Sailing, and then asked if Sachs would consent to trying out a 12-ft. diameter parachute sea anchor. This was to be a "controlled experiment" - same boat, same conditions, but a much larger sea anchor. He agreed, and Shane sent him the sea anchor. Three months later he tried it out in similar conditions and sent back the following report:

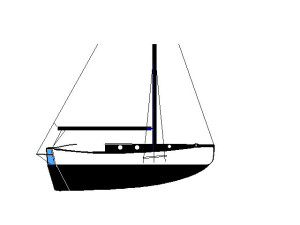

Subject: Test of 12-ft. diameter para-anchor. With westerly winds gusting to 20 mph after the passage of a cold front, we motored offshore to a point outside the Lower Entry harbor on Keweenaw Bay of Lake Superior. With the engine shut off we drifted about 1 knot downwind with the wind and waves off the stern quarter, the same attitude I experienced when unsuccessfully testing my 30-inch conical drogue.

About a mile offshore, in about forty feet of water, I set up the 3/8" laid nylon rode to launch the para-anchor.... As instructed, I launched the float first, which functions as a pilot chute, drawing the para-anchor away from the boat as the boat drifts downwind. This could hardly be easier, for the chute slid overboard and in two or three minutes filled beautifully. Once it filled, it stuck in the water almost like a post and the Venture 222 bow came right up into the wind exactly.

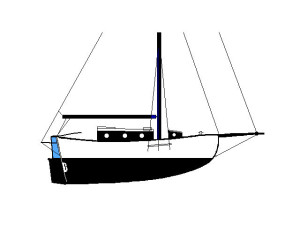

With the keel down the Venture did not yaw more than 10°. With the keel retracted, there was 30°-45° of yaw, as the Venture bottom has almost no lateral resistance with the keel retracted. Rudder was tied amid-ships.

When retrieving the sea anchor, one cannot pull the anchor to the boat. One pulls the boat to the anchor, and that takes strength. I'm glad it wasn't a three ton vessel! Once I could reach the parachute strings, it was dead easy to spill the water out and haul it aboard. Took no effort at all, pulling one string. Once spilled, the para-anchor is a limp sack.We did drift slightly with the anchor. In six minutes the bearing on the lighthouse half a mile away had shifted by ten degrees.... In spite of the holding power, the para-anchor is in a fluid, and the force exerted against it will cause it to slip through the water.

Apart from showing the improvement that can be expected with the use of sea anchor that is large enough, this file reveals something important about centerboards and swing keels as well.

It was previously thought that sailboats would yaw less at sea anchor with their centerboards and keels raised. Not so. At least not on this boat. Apart from tripping on the rudder as the boat surges backward, the CLR moves aft as well. With the CE now so far forward the bow will tend to yaw excessively. When the swing keel is again lowered, however, the CLR moves closer to the CE and the wind doesn't have the same lever. Notwithstanding, boards - and swing keels - should NOT be lowered all the way down in storms.

CAUTION: Lowering board/s and keels, or lowering them all the way, may give the yacht something to trip over in life-threatening storms. By and large, and as an important rule of seamanship, boards and keels should be raised in heavy weather. Or at least raised enough so that the yacht can "slip-slide," and not have a large appendage to hang up on and trip over.