Trimaran, Piver

35' x 20' x 3.5 Tons

4-Ft. Dia. Conical Drogue

Force 12 Conditions

File D/T-8, obtained from Warren L. Thomas, Charleston, SC. - Vessel name Lady Blue Falcon, hailing port Charleston, Lodestar trimaran designed by Arthur Piver, LOA 35' x Beam 20' x Draft 2' x 3.5 Tons - Drogue: 4-ft. Diameter cone, custom-made from heavy mesh (porous) material on 250' x 5/8" nylon three strand tether, with bridle arms of 60' each and bronze swivel - Deployed in an unnamed hurricane about 300 miles north of Bermuda with sustained winds of 80 knots and breaking seas of 30 ft. and greater - Vessel's stern yawed 30° and more with the owner steering.

To quote the immortal words of K. Adlard Coles in Heavy Weather Sailing, "When the wind rises to Force 10 or more and the gray beards ride over the ocean, we arrive at totally different conditions, and for yachts it is battle for survival, as indeed it sometimes may be for big ships." In July 1990, Lady Blue Falcon, one of Arthur Piver's original "Lodestar" designs, was off the northern coast of Maine sailing to Charleston, South Carolina, when she became entwined in a cyclonic system with sustained hurricane-force winds - an unnamed, minor hurricane. What followed was five days of sheer terror for the singlehanded sailor on board, Warren Thomas. The boat was driven without mercy round all points of the compass, eventually finding herself back in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

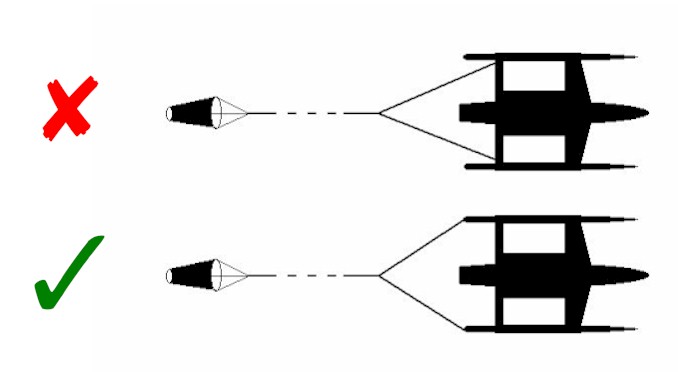

The only drag device on board was a 4-ft. diameter cone, custom made from some sort of tightly knit, porous, nylon mesh material. Thomas deployed it off the stern on 250' of tether and a bridle with 60-ft. arms attached to the outboard sterns of the floats. The bridle would not allow the boat to be steered freely, a major disadvantage in Thomas' opinion. In the chaos that followed, Warren Thomas tried quartering the seas by bringing both bridle arms to one float. This turned out to be a bad idea - made things much worse. To compound matters, the cone would completely pull out of the water at times, allowing the boat to lurch ahead at incredible speeds. The whole experience was traumatic and Thomas' recollection of the details are hazy - "due to complete blank of mind & loss of charts & notes" (to quote Thomas). Transcript:

I used the drogue off the stern of my Piver Lodestar in a mild hurricane 300 miles north of Bermuda, approx. 360 miles east of Cape Cod. Got blown 570 miles in 5 days, running completely out of control. Drogue's bridle would NOT let me steer at high speeds of 22 knots on 2-3 minute continuous runs. (Once rode a gale in Albermorle Sound with 45-55 knots for thirteen hours. It was a walk in the park compared to this.)

Seas in excess of 25 ft. but running faster than HELL! Wave patterns rather organized but about every hour a series of oddballs would come. I could hand-steer them, except at night when I could not see them coming. All this under bare poles. I was alone, scared and just hanging on. It was the biggest horror of my life. The sea won the war! Cannot erase the fury from my mind. First time that I have ever cried like a baby, I believe just from nerves.... Eating raw Taster's Choice right out of the coffee jar.... Wind blew all around compass. Was hovering around 80, gusts exceeding 100. I knew I was going to die. Just did not know when. Mr. tough-guy did die out there. Now only a cautious, humble sailor remains. Took two years to shed the fear and exchange it for a healthy respect for the sea. Am sure I am alive today because of luck only. If I had had a para-anchor I would still have needed luck, but I would have been rested enough to appreciate it!

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!