S/M-39

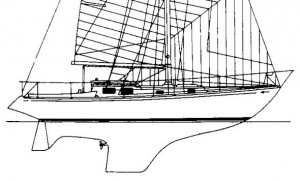

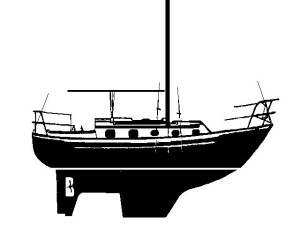

Lotus 9.2 Cutter

30' x 4 Tons, Low Aspect Fin/Skeg

12-Ft. Dia. Sea Anchor

Force 10 Conditions

File S/M-39, obtained from Ann and Jim Wilson, Christchurch, New Zealand - Vessel name Karoro, hailing port Moncks Bay, NZ, Lotus 9.2 sloop, designed by Alan Wright, LOA 30' 2" x LWL 26' 3" x Beam 11' x Draft 5' 6" x 4 Tons - Low aspect fin keel & skeg rudder - Sea anchor: 12-ft. Diameter Para-Tech on 2 lengths of 220' x 5/8" nylon three-strand rode plus 120' of chain and a 35 lb. plow anchor, with 1/2" stainless steel swivel - Partial trip-line - Deployed in a storm in deep water about 400 miles ENE of the North Cape of New Zealand, with sustained winds of 50 knots and seas of 20 feet and greater - Vessel's bow yawed 20° - Drift was about 10 n.m. during 15 hours at sea anchor.

In March 1966, New Zealander Jim Wilson used a 12-ft. Para-Tech sea anchor on Karoro in a gale during a coastal passage from Dunedin to Christchurch. Four months later, en route to Tonga, he used it again in a much heavier storm.

The sea anchor - deployed on two lengths of 220' x 5/8" rope, knotted together with bowlines - held the bow into the waves for a period of fifteen hours, the vessel yawing through a total arc of about 30-45° (about 20° off to each side). The sea anchor was then lost when the rode failed at one of the knots.

Sometime after losing the sea anchor, Karoro was rolled while lying a-hull. This incident confirms the opinion rendered by Peter Blake in File D/T-1: "I don't think lying a-hull is a mode of survival that one should contemplate if conditions are really severe. In moderate conditions, if you're not too worried about the sea state, maybe it's OK. But lying a-hull in a storm is a recipe for being rolled, or having the deck or the cabin top stove in and heavy water come inside. I think that the other approaches are better. Even though lying a-hull is natural and sort of easy, I definitely don't think it's a tactic that people should use, unless they haven't got another option." Most safety experts concur that lying a-hull in a storm is a recipe for disaster.

Here is a transcript of the feedback obtained from Ann and Jim Wilson:

After three good days of sailing to the northeast, out of Gisborne, making over 120 miles a day, we began to feel anxious about warnings of storm-force winds heading our way. The wind increased gradually in intensity and it became clear we would soon be in the storm. Jim went out and put both storm sails up. The mainsail had to be completely removed from the mast to make room for the small orange trysail. The storm jib was hanked onto the [removable] inner forestay, and the furling headsail rolled up completely and lashed. This took some time and Jim finally staggered below, wet and weary. The sails felt comfortable [with the vessel hove-to], but the wind kept gaining in intensity and the forecast was frightening - a band of storm-force winds, 50 knots, 400 miles wide. Soon the waves had become mountainous. I was too scared to look at them.

About 1500 hrs Jim decided to take the storm sails down and put out the sea anchor. He collected three lots of chain, one from under the floor boards, and quietly deliberated on which to use. Then the slow ritual of dressing up and harnessing and emerging into the wild, wet cockpit to sort out sea anchor, buoys and buckets of rope, tying everything up. The sails had to be removed and stowed below, and he finally moved all the gear to the bow. It was starting to get dark. He said he had to get it right the first time or we'd have had it. That put me into a mild state of panic. I followed his movements like a hawk, terrified he'd be washed overboard by a crashing wave and left dangling by his harness. He was wedged in the bow trying to untangle a maze of rope. The wind and waves crashing over were making it worse and his life line kept getting tangled as well. I suddenly felt he'd never sort it out on his own. I began to knock on the hatch window and yell over the sound of the storm, asking if I should come and help. He finally beckoned me out, so I took the headlamp and clipped onto the safety line. Once outside, the force of the wind was terrifying. I was so scared of getting washed off I practically crawled up to the bow and between us we went about untangling the mess of rope.

I found the free end he was looking for, tied the first buoy on and threw it over on Jim's instructions. I hurriedly played out the line which floated backwards. "Bring it in again," shouted Jim, "it's gone under the boat!" I suddenly saw the futility of it all. "It's hopeless," I shouted. At that he said, "OK, OK, throw out the other buoy." Over it went and then finally over went the sea anchor at last. Jim played out the warp and then the chain, and slowly we swung around into the waves. I found it hard to believe it was so much trouble. The whole performance had taken over three hours. (We have since devised a much easier system of deploying it from the cockpit, with chain already through the bow anchor roller fitting, with restraining pin in place, and the chain led back along the toerail, lashed in easy-release fashion, to the cockpit. We should, of course, have devised and tried this system before setting off.)

I crawled back inside. The gentle hove-to movement had changed to a jerky sideways rock, but now we were parting the waves with the bow and not taking them every which way. Jim finally came below and after a cup of hot chocolate we crashed into bed. I discovered that the high pitched whine of the wind, and the way it ascended the scale as it increased in volume, was what depressed me most. That, and the way it stayed at a high pitch for long periods without dropping, and all the frantic rattles and quivering in the rigging and the sudden loud bang as a wave hit us and the water pouring over the decking. I suddenly remembered the wax ear plugs I'd brought along for diving. I jammed a couple in my ears and blissfully all sound disappeared. Only the motion remained. It got me through the night. I think we all had a reasonably good sleep.

Saturday morning, June 22, suddenly Guy said "We're going backwards." Jim saw the loose chain out of the front hatch and said, "My God I think we've lost the sea anchor." My hand flew to my mouth in horror as Jim raced about. "It's OK," said Guy, "it's a much nicer motion now" [the vessel now lying a-hull]. I thought of the sea anchor floating away behind us. Poor Jim was struggling away at the bow, winding in the chain. He'd put so much effort into researching, buying and setting up the sea anchor, and phutt! Just like that, it was gone. He came in and said that the sea anchor warp had broken. He could hardly believe it. It was the same one he'd been towed by, off Akaroa, when the skeg and rudder went. Though he had been towed on these warps, under wild conditions, and therefore thought them tried and true, they were getting old; worse, we only had thimbles spliced in one end of each of the two, the other ends being bowline-knotted, which although tested before under tow (and afterwards, amazingly, the bowlines were undone quite easily) we should have known that a knot is a weak point; and it was at one of the knots that the rope broke.

Jim lashed the tiller to one side and we lay a-hull with no sails. The motion was certainly more comfortable. We put the wooden washboards in the lower half of the companionway and the clear, perspex panel in the top, and slid the hatch cover shut as usual. Sheer stupidity - had we had all the washboards in, instead of this flexible clear upper panel, we would have taken in very little water later.

It was mid-afternoon when we were knocked down. There was no warning. No roar as the rogue wave approached us. It was deceptively quiet and I had momentarily undone my car seat belt that Jim had rigged up in my bunk. I'm not sure why, but I certainly paid for that folly. It seemed like slow motion as I rolled out and hit the table, breaking it off the wall. Then the sound of rushing water. I looked up and saw a waterfall pouring through the gap in the companionway. The clear perspex panel had popped out like a cork. Then Jim was hauling me under the armpits. He said, "We've just been knocked down - we'll come up again." I don't remember coming back up. I was too busy making horrible groaning noises as I struggled to get air into my lungs. My legs were caught in a swirling tangle of quilt, twisting like seaweed in the water. Then I was tossed onto my bed. I seem to remember Jim and Guy baling with buckets.

There was a sharp pain in my ribs and I was straining to breathe, but only getting a small amount of air in. I hoped my lungs weren't perforated. Jim left off baling and raced to the radio. He got through to T.M. [Taupo Maritime] Radio and told them what had happened. "I think I've broken my ribs," I chattered through my teeth, while shivering. A doctor came on the radio and said to take my pulse and respiration, and to keep me as dry as possible. The storm was still raging. We had all the wooden washboards in but there was no guarantee that it wouldn't happen again. Jim and Guy were now as scared as me that we might have another knock down. Jim had strung me in my bunk even more firmly, but every time there was a loud bang on the side of Karoro I'd grab the rail and give a terrified shout.

By Sunday morning, June 23, the storm was over, but we were a depressing sight. I was immobile and on pain killers. The inside was a mess. The radar was out. The new spray dodger had ripped out its attachments, the frame and stainless steel grab rails bent. The VHF aerial was ripped off, and the wind arrow and lights on top of the mast were gone. Blessedly the sun came out. Jim wanted to carry on to Tonga, saying at least we'd be in warm waters then. I couldn't envisage another week at sea. Jim unhappily agreed to go back to New Zealand, although later he realized we'd done the sensible thing. He started the motor, checked out the chart, and found our closest option to be Great Barrier Island. We felt so lucky to have dry batteries, engine and GPS, and the SSB still working. Apart from me getting thrown out of my bunk, we had gotten knocked down on the best side, leaving the batteries high and dry. We turned and headed back. By evening there was some semblance of order.

The next few days are pretty much blurred in my mind. I remember constantly asking "what day is it?" Time seemed to go so slowly. Nights were quicker with escape into sleep. We ran into strong northwesterlies. By Monday we were beating into 40-knot winds.... On Tuesday night we were closing in, but Taupo Maritime Radio had for some time been broadcasting navigational warnings of the New Zealand Navy's target practice along the Coromandel Coast... we were right in their firing line! Jim contacted T.M.R. and told them we'd been knocked down, on our way back, and in the line of fire. It was comic. Racing into stormy winds and big waves, saved from the depths of the sea, only to be fired on by our own navy. Guy and I were cracking up - me painfully....

On the quiet, still, cloudy morning of Thursday June 27, 1996 we motored into Tauranga. I had dropped into a deep sleep. I finally came to with the sound of voices. Jim was talking to a man who was helping us tie up alongside the marine. We'd made it!

Did the Wilsons sell the boat and buy a cozy little sheep farm inland? No! Ann & Jim recently returned from another long trip! Jim Wilson's hand-written note on the filled out DDDB form that Victor Shane had been anxiously waiting for reads thus: "Just returned from 6 months on Karoro, to Tonga and back. No need for sea anchor this time - no knockdowns! But very glad we had a replacement on board. Wouldn't now go to sea without one."