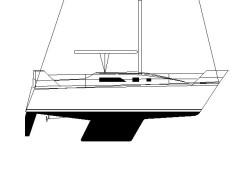

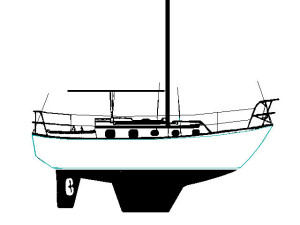

Monohull, Pearson 424C

42' x 11 Tons, Low Aspect Fin Keel

18-Ft. Dia. Sea Anchor

Force 8-9 Conditions

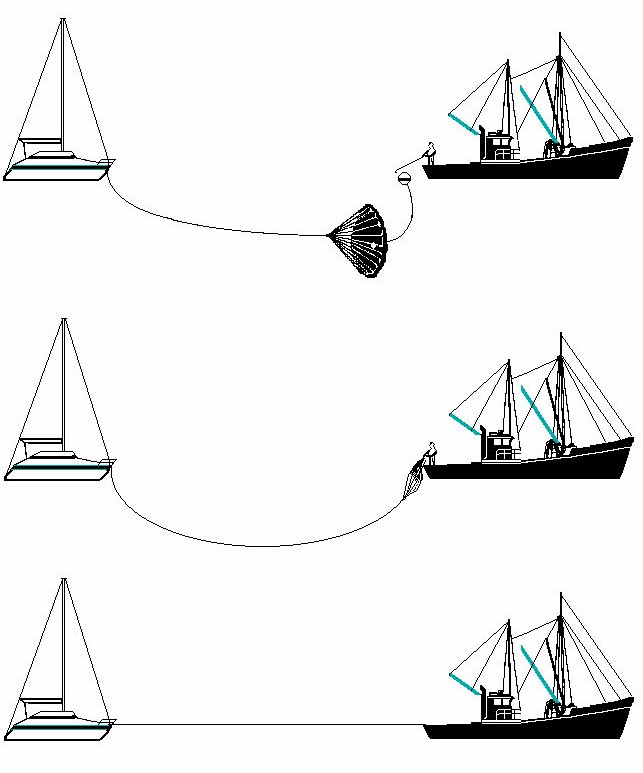

File S/M-37, obtained from William T. Dwyer, Jr., Chicago, IL. - Vessel name Overdraft, hailing port Chicago, Pearson 424C cutter, designed by William Shaw, LOA 42.4' x LWL 33' 8" x Beam 13' x Draft 5' 6" x 11 Tons - Low aspect fin & skeg rudder - Sea anchor: 18-ft. Diameter Para-Tech on 300' x 5/8" nylon braid rode with 5/8" stainless steel swivel - Partial trip line - Deployed in a gale in deep water about 350 miles NW of Bermuda, with winds of 35-45 knots and seas of 12-20 feet - Vessel's bow yawed 20° - Drift was undetermined due to the proximity of the Gulf Stream.

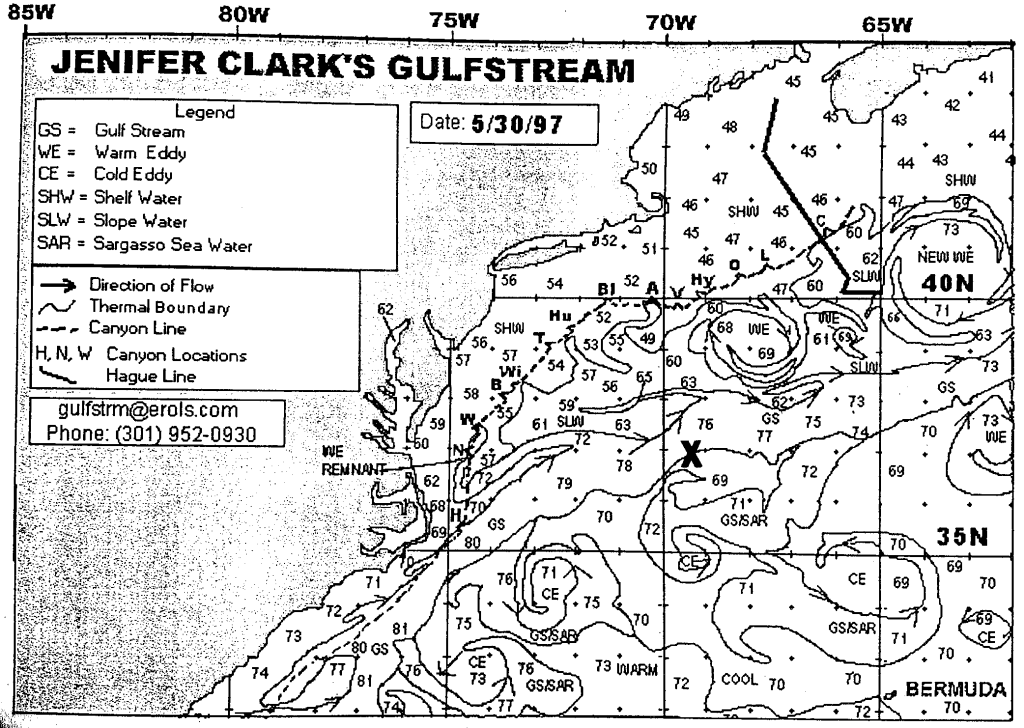

The Gulf Stream is a 60-mile wide, swift (up to 5-knot) eastward flowing current. Past Cape Hatteras the stream is known to meander from side to side like a river. These meanders may change periodically, peeling off from the main body of the stream to form intense eddies. The eddies are sometimes called "rings." As the Stream moves eastward, warm rings are formed to its north and cold rings to its south. These discrete rings often migrate and meet back up with the main body of the Stream after months, or sometimes years.

Since the Gulf Stream transports warm water from southern latitudes one can usually tell whether one is entering or exiting it by the abrupt change in water temperature. At its edges, and deeper down, the Stream consists of a distinct, temperature gradient. This thermal gradient may extend deeper than 6000 ft. beneath the Stream.

Since cold water tends to dive beneath warm water, theoretically it may take a large sea anchor down with it - if it is deployed at an exact boundary zone. This is something that one has to be cautious of if one has to use a sea anchor in the Gulf Stream, especially in the fringes of a cold eddy. If this is the case one should rig a full trip line, one that allows the canopy to be readily tripped and retrieved without having to power up to the secondary float of a partial trip line. Otherwise the anchor may have to be cut away. There may be a possibility that this is what may have happened in the case of the S/V Overdraft. Transcript:

We departed Newport, RI on the afternoon of June 1, 1997 bound for the Mediterranean via the Azores. NOAA and a private weather forecaster called for NE winds 20-30 kts and recurring low pressure systems along a frontal boundary lying east to west along the 40th parallel, dropping to the southeast. Our plan was to sail SSE to approximately 38° N where we would cross the Gulf Stream and then sail SE until we encountered the westerlies. The going was rough, with winds from the NE higher than predicted.

Some time in the early morning of June 3, we entered the Gulf Stream heading south. Winds over the prior 24 hours had been NE at Force 6 to 7. Throughout the morning, winds increased to Force 8 to 9 with one observed gust of 55 kts apparent. We were sailing downwind in a following sea doing 8+ kts by the speedo. The waves became tall (10-12' with frequently higher waves of approximately 20'), and steep, as the seas ran counter to the Gulf Stream. Graybeards covered the sea as the tops of the waves broke against the current. We were sailing almost due south with the wind against the current, and although our knotmeter was registering hull speed, we were making approximately 4 kts over the bottom according to the GPS. I determined that we could not exit the Stream before nightfall on our current course, and decided to attempt to head ESE to escape these dangerous conditions before dark.

We proceeded ESE under staysail, deeply reefed main and engine to maintain as much directional control as possible. We took the non-breaking waves just aft of the beam and fell off to take the large breakers on our port quarter, or headed quickly up to take them at a 60° angle off the port bow. On three occasions when attempting to run off we were caught by a breaker and broached to starboard with the spreaders in the water and the wave breaking over the port side, filling the cockpit with 2½ feet of green water. By dusk we had reached the edge of the Gulf Stream, which we determined by a significant drop in water temperature. The waves became more trochoidal [rounded] in shape with fewer breakers. I decided at this point to set the sea anchor for the night as the crew had experienced miserable weather for three days and had no food or sleep for almost 24 hours.

An 18 foot Para-Tech sea anchor was deployed off the bow on 300' of 5/8" nylon braid line with 5/8" stainless swivel and no chain. The para-anchor had the standard float line with a 12" diameter plastic float buoy securely attached. After deployment the boat lay bow to the wind and did not yaw significantly from side to side, although Overdraft continued to pitch sharply, as the seas, while improved, were still quite steep. The boat lay to the sea anchor all night in winds of Force 7 decreasing to Force 6. Seas remained at about 8 feet.

At first light, we found that the rode was pointed downward at an angle of 35-45° off the port bow. Overnight the rode had chafed through the teak cap rail below the chock in an arc, cutting downward 3/4" to 1" into the wood. It was apparent that the boat was being pulled by the para-anchor in a northeasterly direction against the wind and sea. A comparison to the position check at the time the anchor was set showed we had move NE more than 3 nm overnight. The strain on the anchor rode was significant.

We attempted to retrieve the sea anchor by motoring in the direction of the anchor and pulling on the line - without success. The anchor seemed to dive deeper as we motored towards it, and we were only able to recover line as the boat rode down into a trough. As Overdraft rode back up the next crest, the rode was cleated and came under extreme tension with the anchor pulling downward on the bow. The wind was beginning to increase again and I feared that the crew attempting to retrieve the anchor by uncleating and cleating the line between waves could suffer serious hand injury, given the tension on the rode and the sea states. At this point I cut the anchor away. We had only recovered about 10 feet of line.

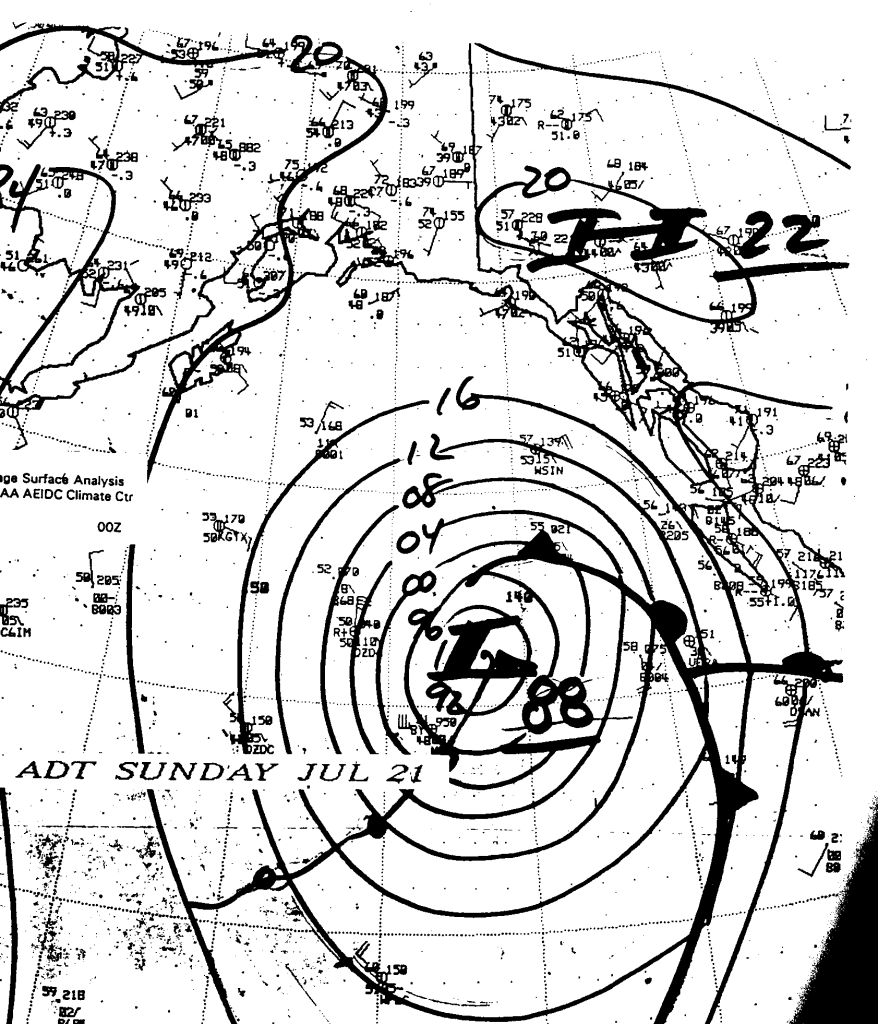

My supposition is that we had not sailed completely out of the Gulf Stream, and that the sea anchor was pulled downward by the northeasterly flowing current which may have been stronger at depth because of the counter-acting surface conditions caused by wind and waves. I do not believe the float became detached as it was securely tied and floating free upon deployment. Clearly, we were still in the influence of the Stream or we could not have moved northeast overnight against the wind and sea. An attempt to plot our position on a May 30th Gulf Stream analysis weather fax is enclosed, and it shows us at approximately the edge of the Stream on 0700 June 4. I find our overnight drift the more compelling evidence that we were still in the Stream because the potential plotting error of both the boat's position and the Gulf Stream location on this large scale fax is very large. For what it is worth, I don't believe setting the para-anchor in full current of the Gulf Stream in the conditions we experienced would have been a successful strategy. Because of the steepness of the seas and their frequent breaking, the boat would have taken a terrible pounding. The current would have pulled us NE into the seas, and because the anchor "dove," the bow would have been held down, further impeding the boat's ability to ride over the breaking seas. This experience has convinced me that (not even considering the loss of the gear) a sea anchor should not be set in a strong current running counter to the wind and seas except in a case of absolute last resort.

CAUTION: Do not deploy a large sea anchor in the axis of a major current unless it is absolutely necessary. Use a full trip line if you do, else stand ready to cut away the rode if you are absolutely certain that a cold eddy is taking the parachute down into the depths. You will be able to tell that this is so when the main float begins submerging and then finally disappears, by the significant increase in the angle at which the rode is leading downward, and by an unmistakable downward pull on the bow of the vessel.

If you are in the vicinity of a major current and there is a gale on the way, the best strategy is to try to traverse the current at right angles and get well clear before deploying the sea anchor. By and large ocean currents are a mixed blessing. The free ride that they may provide can be very costly at times. Some experienced sailors prefer to stay out of them altogether. The Pardeys have this to say about major currents in Storm Tactics: "Another thing we've learned the hard way is to avoid the axis of major currents. Even though it is tempting to grab the free lift offered by the Gulf Stream, you increase your chances of meeting unusual weather patterns and rougher seas."

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!