S/C-6B

Catamaran, Crowther

43' x 25' x 7.5 Tons

18-Ft. Dia. Sea Anchor

Force 10 Conditions

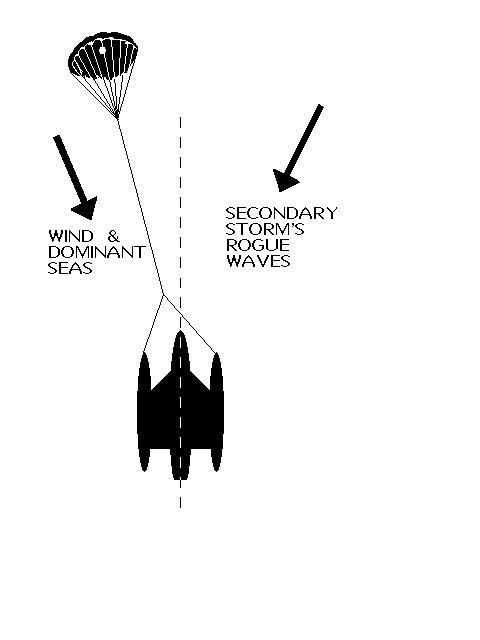

File S/C-6B, second file (see S/C-6A) obtained from Josh Tofield of Tucson, AZ. - SAME VESSEL - SAME SEA ANCHOR - SAME BRIDLE & TETHER DIMENSIONS - Deployed in a storm in deep water about 800 miles northeast of Hawaii with winds of 50-55 knots and seas of 25 ft. - Vessel's bow yawed 10° - Drift was 5 n.m. during 72 hours at sea anchor.

This is the second file involving Ariel. In the previous file she successfully rode out Force 8-9 conditions on the same parachute with a 250' tether. In this file we see that the 250' tether was clearly too short when Ariel ran into a much heavier storm on her way back from Hawaii. The 250' x 3/4" tether was not long enough to provide adequate shock absorption, as a result of which the boat took a severe pounding. Ariel's tether should have been at least 400' in this instance (the general rule of thumb being LOA x 10). Transcript:

Ariel departed Hawaii 11/10/91 with delivery skipper aboard. He has documented over 100,000 miles in deliveries for Compass Yacht Services alone. Approx. 800 miles NE of Honolulu a rapidly moving, intense LOW which was squeezing against a massive hi-pressure cell caught Ariel in the exact center of reinforced winds. Barometer dropped from 1018 to 1002 in 3 hours! (Weather Fax attached). Wind started one hour later and built to Force 10 where it stayed, never dropping below Force 9 in 48 hours. Waves were 25' (conservatively measured from the back of wave height and not from the troughs). Bridle (3/4" nylon) chafed completely through & had to be replaced with 5/8" backup bridle. Later one leg of the 5/8" bridle SNAPPED in the center when hit with very large wave, throwing Ariel backward, shearing the foam & fiberglass off of one rudder completely, and leaving only half of the other rudder (which later broke off). Crew eventually added 100-150' of anchor chain to the 250' of 3/4" nylon tether and rode out the rest of the storm.

Recovery, using the "partial trip line" was very difficult. Engines both out because during the storm, while motoring up to relieve pressure on bridle (while changing it) a large wave submerged entire stern, forcing water up exhaust system and drowning the engines (exhausts 2' above waterline under aft bridge deck !!!!!) Jury rigging done after storm passed. Ariel was then sailed 1500 miles to San Diego. Moral of the story: USE LOTS OF PRIMARY TETHER! What is adequate for Force 9 is not adequate for Force 10!