S/T-1

S/T-1

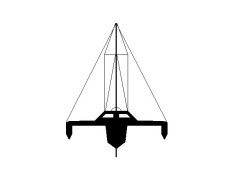

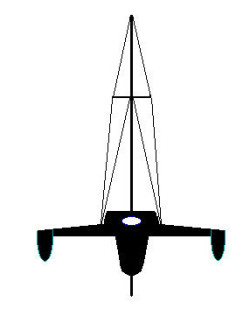

Trimaran, Horstman Tristar Ketch

39' x 22' x 8 Tons

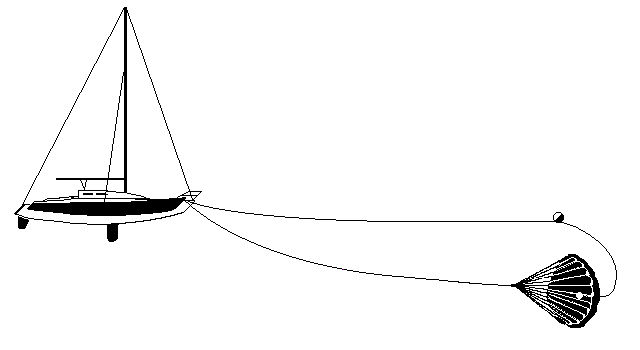

28-Ft. Dia. Parachute Sea Anchor

Force 12 Conditions

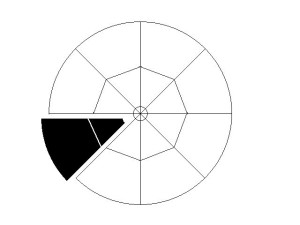

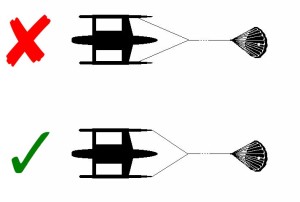

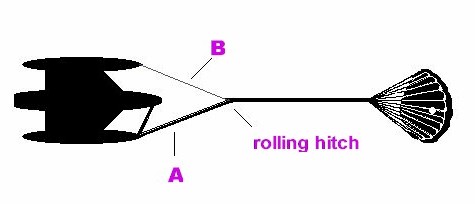

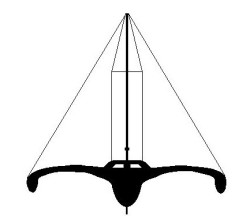

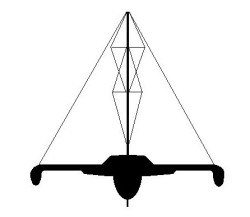

File S/T-1, obtained from Joan Casanova, Oregon City, OR. - Vessel name Tortuga Too, hailing port Seattle, Trimaran, Tristar ketch, designed by Ed Horstman, LOA 39' x Beam 22' x Draft 44" x 8 Tons - Sea anchor: 28-ft. Diameter C-9 military class parachute on 400' x 3/4" nylon three strand tether and bridle arms of 60' each, with 1/2" galvanized swivel - Full trip line - Deployed in numerous storms during 18-year cruise from Seattle to African coast, the Southern Ocean and back to Texas - Severest use case was over the Burwood Bank, between Cape Horn and Falkland Islands, with winds of 85-100 knots and seas in excess of 30' - Vessel's bow yawed about 20° - Drift was estimated to be 16 n.m. during three days at sea anchor.

By and large this is probably the most important file in the Drag Device Data Base. Other than a handful of known but poorly-documented cases of commercial fishermen and some sailboats using parachutes, our knowledge about the general behavior of boats at sea anchor was sketchy until the Casanovas came alone. We didn't know if a boat would "rise to the seas," or be pulled through green water. We didn't know if the boat would roll with the punches and "yield to the seas," or stand up against them and break up. We didn't know if the boat would get "slingshotted" off the crests as the elastic rode stretched. We didn't know if the boat would "back down" on her rudder, so as to cause it to break off. We didn't know if the hardware and fittings on boats could withstand the forces involved. Well, thanks to the pioneering work of Joan and John Casanova, now we know.

The parachute anchoring system never failed on Tortuga Too, not once in eighteen years and some 200,000 blue water miles. Off the coast of New Zealand where cyclone winds were recorded at 90 mph, in a hurricane off Fiji where several other boats were lost, in 40-ft. seas in the Indian Ocean, and in a truly devastating storm off the Falklands, time and again Tortuga Too survived without damage by the correct use of the parachute sea anchor. While Lady Luck might have played a significant role in some of the other files in this database, it is clear that her role was minimal in this one. Indeed, the number of times that the parachute was used, and the broad range of life-threatening storms and heavy weather situations in which it was deployed, seem to tell us that luck had very little to do with anything here - though it goes without saying that luck always favors the wise and the well-prepared.

Despite her relatively lightweight - plywood - construction, and despite her 22-ft. beam, Tortuga Too was never in any danger of breaking up. Not once did she get slingshotted off the huge storm crests; she never went crashing through green water; the galvanized swivel did not fail; the deck fittings did not pull out. The 28-ft. diameter military parachute held and the system worked, time and time again.

Tortuga Too's worst-case scenario occurred over the shallow Burwood Bank, between Cape Horn and the Falklands. This was a "bomb" type storm development, to use the expression coined by professor Fred Sanders of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The term "bomb" is generally used to describe the rapid development of a secondary storm, which overtakes - and reinforces - its predecessor. In particular it describes the pressure gradient amplifications that result from the overtaking of a surface LOW by a faster moving upper altitude TROUGH, resulting in barometric pressure decreases of 24 millibars or more in a 24-hour period, as well as abruptly angled surface wind fields. This type of storm development - usually identified by high-altitude comma-shaped clouds on satellites pictures - was associated with Fastnet '79.

In the book The Parachute Anchoring System Joan Casanova describes Tortuga Too's encounter with a genuine ESW - extreme storm wave. Tortuga Too was tethered to a 28-ft. diameter C-9 parachute when an enormous mountain of curling, roaring water rose before her bows, something akin to the terrifying photographs in Coles's Heavy Weather Sailing. This sobering account should be a source of comfort to multihull sailors in particular. It is reproduced by permission of Chiodi Advertising & Publishing, publisher of Multihulls Magazine:

It was the type of a wave which pitchpoles yachts in these oceans, the type which every voyager sailing in the high latitudes of the Southern Ocean fears. While we watched, horrified, this monster welled up for a second time, curling over as if breaking on a beach, then roaring in foamy masses on top of Tortuga Too, covering deck and wheel house before running off into the sea once more. We were so shaken by this experience that it seemed an eternity before we regained our composure to check the boat's condition, but she was all right. In fact, Tortuga Too recovered faster than we. There was no structural damage. She had returned to her original position of facing the storm and was already climbing the next wave....

We want to stress here that no vessel, multihull, monohull or freighter, could have survived such a sea unless tethered with a long line from a sea anchor... we share this story with you only to prove how this technique can protect a craft in extraordinary circumstances. Although Tortuga Too survived this mammoth wave crashing on her deck, there was no backing down on her rudder, nor any structural damage to the hulls.

The experiences of the Casanovas with parachute sea anchors is so broad-based, so extensive that it has entered into the legend and nomenclature of multihull sailing. In the multihull community the name "Casanova" is synonymous with parachute anchoring, to the extent that the names "Voss" and "Pardey" are synonymous with heaving-to in the monohull community. In the course of logging all those blue water miles, Joan and "Cass" tried every conceivable heavy weather tactic known to man, including the use of makeshift drogues off the stern, but they always found themselves coming back to the bow-deployed parachute sea anchor. Multihull sailors owe a debt of deep gratitude to Joan Casanova in particular, for having the vision to see in her valuable storm experiences a responsibility to inform others. (See also her early articles in the Spring 1976, July/August 1979 and August 1980 issues of Multihulls Magazine).

Love the Drag Device Database? Help us to keep it free for all mariners by making a tiny donation to cover our server and maintenance costs. Thank You!

S/T-3

S/T-3